The Paris Agreement on climate change was hailed as the moment when 195 countries set aside their differences to tackle a common challenge.

Five months on, was it all too good to be true? The outlook is mixed, say envoys and analysts who followed the last two weeks of UN climate talks in Bonn.

On the surface, the atmosphere was positive. “We are moving beyond previous disagreements from the past few years,” said Elina Bardram, the EU’s chief negotiator.

“We’ve had a positive tone over the 2 weeks; clear evidence the spirit of Paris is still there,” said her European colleague, Dutch envoy Ivo de Zwaan.

“Everybody is committed, and this is the message we are getting out of the negotiators,” said Christian Aid advisor Mohamed Adow.

In a sign of the general good humour, hundreds of delegates stood and sang “Climate Queen”, a reworked version of the 1970s Abba classic, to outgoing UN climate chief Christiana Figueres.

But behind closed doors, observers say tensions persist between wealthy nations who are expected to pick up the bill for a proposed green transition, and historically poorer countries.

“The support issue is a priority issue,” said China’s chief climate negotiator Su Wei in an interview with the Xinhua news agency on Thursday.

Developing countries need more than $3 trillion to deliver on the climate plans (now known in UN jargon as NDCs) they submitted to the UN in 2015.

In a sign of frustration at the slow trickle of funding and green technology filtering to the developing world, this week 90 countries called for this year’s main UN climate meeting in Marrakech, Morocco to be a “renewable energy summit”.

The initial aim is to ensure Africa enjoys 10 gigawatts of new green power by 2020.

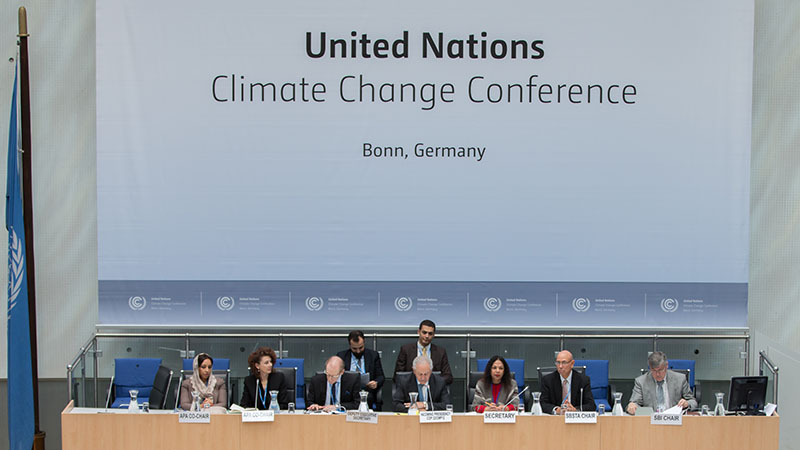

Sarah Bashaan and Jo Tyndall, chairs of the ‘APA’ set of talks on the Paris Agreement (Pic: UNFCCC/Flickr)

“This initiative is aiming at leaving no vulnerable country behind when it comes to renewable energy,” said Tosi Mpanu Mpanu, chair of the group of Least Developed Countries.

By Marrakech in November, the initiative will have a “pipeline of projects” needing support, said Ambassador Hussein Alfa Nafo, Malian diplomat who chairs African Group of nations.

“Without such an effort prospects of achieving 1.5C are low, and risks to small islands are great,” said Amjad Abdulla, head of the Alliance of Small Island States in Bonn.

So far $10 billion for this project has been offered by developed countries including the US, UK and European Union, but more will likely be needed said Nafo.

It is one front in a wider fight poorer countries say they are in to gain access to a promised US$100 billion a year by 2020 plus access to cleaner technologies.

Rule book

If the need for more money to fund clean energy is one headache that will dominate Marrakech, so too is the need to work out how the 31-page Paris Agreement will actually work.

“The outcome in Paris reflected consensus reached by parties on principle issues, but some contents of the agreement need clarification,” said China’s Su.

Top of the list is the need for a rules to administer the new agreement. The scale and complexity of this legal and technical challenge is “daunting” said Liz Gallagher, senior associate with the E3G thinktank.

The rules for the Kyoto Protocol – the last major UN climate pact – took five years to develop. This time the estimate is two, said France’s climate ambassador Laurence Tubiana.

When complete, they will detail how countries should count and report greenhouse gas emissions, and what is required to adapt to projected extreme weather events like floods and drought.

Analysis: Vague national climate plans pose a transparency problem

Envoys need to work out what will be included in their climate plans or NDCs, the scope of market mechanisms, how finance flows should be counted and how tough a new transparency system will be on developing countries.

Many poorer African and Asian countries argue they lack the capacity to sign up to a strict measuring system and need greater levels of funding before they can comply.

It raises the question of whether the talks will once again split between rich and poor over the toxic issue of differentiation, which many thought put to bed in Paris last December.

“Part of this is rhetoric – when you unpack it this is less of a real issue,” argued Jake Schmidt, climate director at the DC-based Natural Resources Defense Council.

Sweet harmony: Why UN climate plans should use the same metrics

Still, differentiation now plays out across a broad range of issues such as climate finance and transparency – the most obvious area where a two-speed approach is being discussed.

“It’s certainly a latent issue; I expect it will return,” said Elliot Diringer, a former White House advisor who now works at the Washington DC thinktank C2ES.

“The aim of developed countries is a common framework, but some are beginning to define a built-in flexibility in a way that might seem to be a reversion to a bifurcated system,” he added.

Described as one of the “knotty issues” by China’s Su, the US and EU regard a common set of metrics as essential ahead of 2018, when the UN has scheduled a “stocktake” of global climate efforts.

“Transparency dictates everything. It is the backbone of the Paris agreement and ensures we can keep track of our long term goals,” said the EU’s Bardram.

“If we don’t have valid data across world we cannot have a clear conversation.”