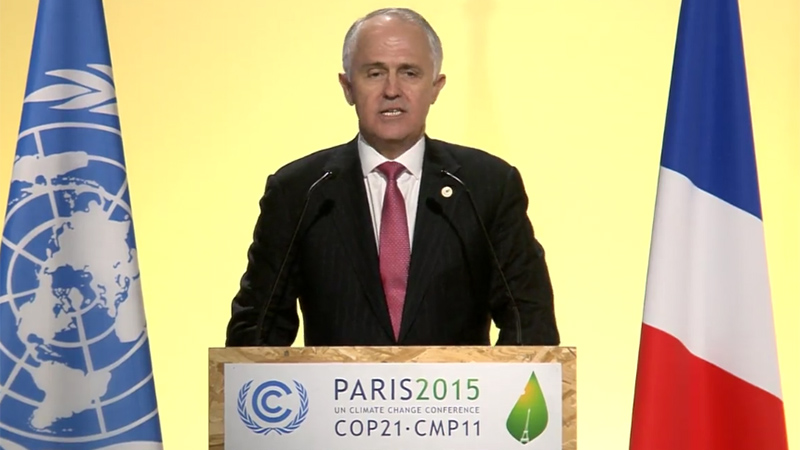

At the Paris summit in late 2015, Australia’s reputation as a climate obstructionist, built under the leadership of Tony Abbott, seemed to be on the mend.

Just a few months into the leadership of Malcolm Turnbull, the country had arrived with positive rhetoric and negotiators spoke of a new, constructive attitude the antipodeans had brought to France.

But the journey in from the cold is not yet complete. In April, the country was not invited to attend a meeting of the ‘high ambition coalition’; a group that it had asked to join and even said it was a part of.

In answer to the developing world’s call for $100bn each year from the rich, Australia has signed over $187m to the Green Climate Fund, which it currently co-chairs. This money was not new, but redirected from the existing foreign aid budget.

Weekly briefing: Sign up for your essential climate politics update

In 2015, Australia submitted an emissions reduction target of 26% below 2005 levels by 2030. This was rated as inadequate by Berlin-based policy institute Climate Analytics and “pathetic” by John Connor, CEO of the Climate Institute and Prof Will Steffen, a climate change expert and researcher at the Australian National University.

After scrapping a carbon tax in 2012, the conservative government has stuck to its centrepiece “direct action” policy, which pays polluters to cut emissions. This is widely thought to be insufficient for meeting the existing low targets.

Even prime minister Turnbull has described the policy (before he inherited it) as “bullshit” and “very expensive”. The $2.5bn set aside for the policy is likely to run out before the next budget cycle.

G20 countries per capita emissions in 2030

However a report released this week by the Climate Institute found that the opposition Labor party’s policy was better, but still not an equitable share of the world’s climate burden.

Australia has one of the highest per capita carbon footprints of all countries. Its 2020 emissions reduction target will only be met because it is using about 100 million tonnes of credits it has left over from beating its 2012 target under the Kyoto Protocol.

It may be the only country in the world to be using such a bare-faced accounting trick.

“Despite what [former environment minister] Greg Hunt says. The fact is that our emissions have increased since the repeal of the carbon pricing mechanism,” says Connor.

Little substantive has happened in the policy arena since December. The government has been preoccupied with a July election they barely scraped through.

Bushfires, floods and storms in 2016 have raised public concern about climate change in Australia (Flickr/Shek Graham)

But almost a year on from Paris, observers can sense change in the air.

Climate policy in Australia has long been lost in a wilderness of mining interests and political gamesmanship. For almost a decade, the right has successfully used attempts to place market controls on carbon as a political wedge. Prime minsters and oppositions leaders alike have fallen on this third political rail.

Perversely the fact climate policy featured little in the election campaign may be no bad thing, says Connor. “It certainly wasn’t the scaremongering that we’ve seen from the coalition in the past.”

The public appetite for these campaigns has diminished; people of all political persuasions want the government to do more. Polling by the Climate Institute found that between 2013 and 2016 concern about climate change among the proportion those who voted for the governing coalition grew from 41% to 62%.

This has been driven partly by the lived experience of recent wild weather. Australia’s climate is particularly vulnerable to the distress of El Niño years.

In 2016, bushfires and drought have ripped apart both precious wilderness and farming communities; huge storms took the very foundations from beneath Sydney’s most affluent suburbs; floods drowned the rural towns of northern Tasmania.

While the link between climate change and these events is complex, there were few Australians in the past year who did not notice that the weather had been acting strangely – many have drawn their own conclusions.

Coming up… first in a new series: the Paris temperature check. Guess who @KarlMathiesen is starting with… pic.twitter.com/9dwvmOo2UD

— Climate Home News (@ClimateHome) August 26, 2016

Within the machinery of government, the energy and environment ministries have recently been folded into one. Making the man who once described the “moral case” for coal, Josh Frydenberg, the tsar of Australia’s climate change response.

But Frydenberg has confounded critics and fanned hope by smacking down suggestions that wind power had caused an electricity price spike in South Australia.

He has also modified his line on coal. “What I would say is coal remains an important part of the energy mix but it is a declining share of the energy mix and that is not a bad thing,” he told the Saturday Paper in a recent interview.

The country took ten years to ratify the Kyoto Protocol, yet it has indicated it intends to ratify the Paris agreement this year.

A spokesperson for the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade said: “We will commence the ratification process shortly. Ratification is subject to parliamentary processes.”

In Australia, treaty ratification does have to be reviewed by parliament but the final decision is the prerogative of the government, meaning Turnbull and Frydenberg may face an arm wrestle with their right-wing cabinet colleagues.

The official said Australia’s decision to accept the invitation of UN secretary general Ban Ki Moon to a special event for ratification on September 21 of this year was “under consideration”.

The government is set for a major review of its climate policy in 2017. At that moment, there is opportunity for a shift. The review could, for example, trigger a “baseline and cap” scheme hidden with the current policy by increasing the requirements for polluters to cut emissions.

A spokesperson for the newly minted department of energy and environment told Climate Home the existing policies were “comprehensive and enduring” and were “making headway on our 2030 target”.

The spokesperson added: “The Government will take stock of Australia’s policies in 2017, taking account of the 2030 target. This process will build on our established policies.”

But until that moment, says Steffen, the nation is effectively holding its breath. “We are still waiting. That’s the bottom line. There is no firm direction backed up by firm and understandable plans to get emissions down. It’s just a lot of hot air and conjecture at the moment,” he says.

Steffen says the real indicator that Australia’s policies are heading in the right direction would be the advent of a renewables boom. Australia is abundant in coal and natural gas, and so fossil fuels continue to dominate its production of energy.

It also has enormous potential for renewable growth – solar and wind energy in particular. Yet the share of renewables has barely changed in 30 years.

“[Investors] need some long term certainty of where the government’s going to go for them to be able to invest,” says Steffen. “We are not seeing a big upswing in investment after the election. They are still hanging back to see how the landscape is going to change.”

Investment in renewable energy has evaporated in recent years as the government bungled a review of the sector. The number of jobs in the renewable sector has fallen and new installations are at a seven-year low.

“It’s all still finely balanced,” says Connor.

We’ll be working our way through the world’s top carbon polluters as the #Paristemperaturecheck continues. If you have any comments, tips or suggestions contact Karl at [email protected] or tweet @KarlMathiesen