It was only fitting that the two emails arrived almost simultaneously. One was from the White House press office in which president Barack Obama hailed the movement of the Paris climate agreement into international law.

In the other, an automated Australian Parliament House server noted that the Joint Standing Committee on Treaties was now holding public consultations on the ratification of the climate accord.

On Wednesday, world leaders had sent out press releases and tweets to chorus their achievement.

“History may well judge it as a turning point for our planet,” said Obama.

“What once seemed unthinkable is now unstoppable,” said UN secretary general Ban Ki Moon.

Australia’s government was silent.

"What once seemed unthinkable is now unstoppable" #UNSG as #ParisAgreement on #climatechange goes into force 4 Nov https://t.co/t9xFZwdKgk pic.twitter.com/plRHqZi2ju

— UN Spokesperson (@UN_Spokesperson) October 5, 2016

Two thirds of Australians want their country to be a leader in the climate field. Yet when countries gather in Marrakech in a month for what will now be the first meeting of the parties to the Paris agreement, Australia will remain on the outside.

This is not just symbolic. When countries meet in Morocco issues of national consequence will be discussed.

On Wednesday, as New Zealand announced it had formally joined the treaty, the climate change minister Paula Bennett said the move would give her country “a seat at the decision-making table on matters that affect the Paris agreement”. For New Zealand that means trying to eke out advantageous accounting rules to benefit its major forestry and agriculture industries.

Governments are accelerating #ClimateAction: #ParisAgreement’s governing body to meet for 1st time at #COP22 https://t.co/SLI4uoRYVG pic.twitter.com/exVXqGy3Vw

— Patricia Espinosa C. (@PEspinosaC) October 5, 2016

“There’s a real procedural issue in theory, because if you don’t ratify the agreement then you don’t have decision-making power,” said Erwin Jackson, deputy CEO of the Climate Institute, an Australian thinktank.

Australia is not alone. There are 123 other countries that have not yet signed up. Although when all the EU member states have formally joined it will leave Chile, Israel, Japan, Turkey and Australia as the only OECD members on the outer.

Jackson said the problem of so many non-ratified countries would have to be delicately handled by the Moroccan chair. Excluding nations who are still pushing through their domestic process “would probably be quite damaging in terms of longer term trust in the agreement and making sure there’s broad buy-in”.

Weekly briefing: Sign up for your essential climate politics update

There is a process that governs Australia’s entry into foreign treaties. The standing committee is given a fixed time to conduct public hearings before returning a report to the parliament. Because the government did not begin this process until 31 August, the standing committee will not return its report until 8 November or just before. Meaning there is no chance of Australia being part of the Paris agreement before the Marrakech meeting.

Fairfax reported on Thursday that the government was blaming the delay on this year’s election, which curtailed all committee activity between May and September.

But the Paris agreement actually sits underneath an existing treaty, meaning the process could have been expedited. This is what allowed President Obama to bypass the senate in the US.

“In theory the ratification is in the hands of the executive,” said Jackson. “But in terms of the politics in Australia and ensuring there is bipartisan support for the agreement it’s better to respect the domestic processes and allow them to go their course.”

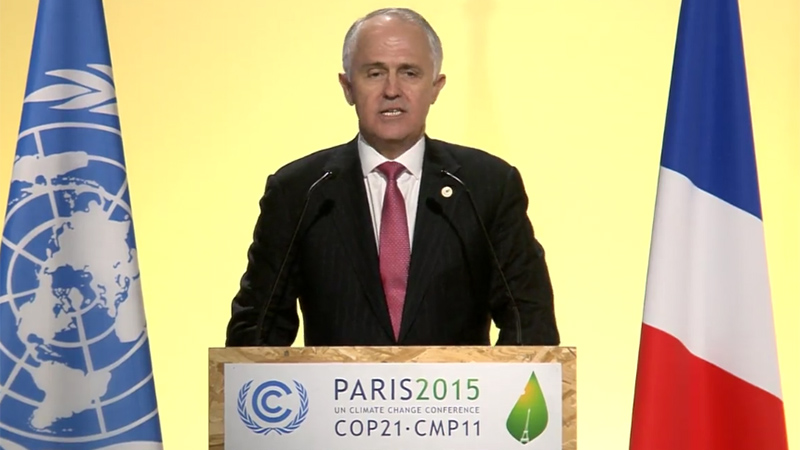

That’s a politics that continues to be defined by a problematic relationship with fossil fuels. When Jackson says bipartisan, it’s not the Labour opposition prime minister Malcolm Turnbull has to convince to support ratification but his own governmental colleagues.

Source: Crikey

This week the climate story dominating Australian discourse was an opportunistic attack on state renewable energy targets, led by a reconstructed Turnbull, who used a state-wide blackout caused by a powerful storm knocking down power lines to start a national conversation on the instability of renewable energy.

This is the same Turnbull who once crossed the floor (a near sacrilegious act in Australian parliament) to support Labour’s emissions trading scheme because it was the right thing to do.

Amid the furore over South Australia, Crikey’s political editor Bernard Keane compiled a revealing graph. It shows the surge in fossil fuel donations to Turnbull’s ruling Coalition parties during the last election year.

Data for this year is not yet available, but if it followed the same pre-election pattern, Turnbull’s party coffers would have been filling just as the window for Australia to join the climate vanguard was closing.