Saudi Arabia is seeking to secure oil trade routes to east Asia through a multi-billion dollar investment in a Maldives atoll, foreign policy experts and the Maldives’ former president have told Climate Home.

The move could prefigure a Chinese military expansion into the heart of the Indian Ocean, one observer said.

The economic future of the Saudi petro-kingdom is bound to the sale of oil, gas and other goods to China. The supply lines for that trade run through the Indian Ocean, where terror is a growing concern and vessels are shadowed by piracy.

The ships also pass by the Maldives – an 820km-long chain of atolls southwest of the tip of India. In this small country, with its growing Wahhabist majority and autocratic government, the Saudis have found – or, according to the Maldivian opposition, created – a pliant ally where few questions are asked and fewer are allowed.

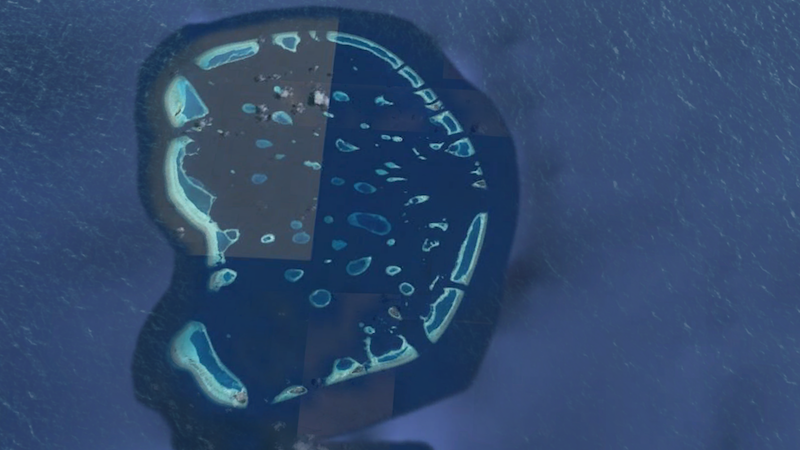

Last week, unconfirmed reports emerged that the Saudi government intended to buy one of the atolls, Faafu – a collection of 19 low-lying islands 120 kilometres south of the capital Malé and home to 4,000 people.

Weekly briefing: Sign up for your essential climate news update

President Abdulla Yameen Abdul Gayoom has denied the entire atoll will be sold to the Saudis, but said plans for a “mega project” worth US$10 billion – three times his country’s GDP – would be disclosed “once the negotiation process was completed”.

Former-president and opposition leader Mohamed Nasheed said the reported sale of Faafu, which has been subject to no public tender process, was “disturbing”.

“[The Saudis] want to have a base in the Maldives that would safeguard the trade routes, their oil routes, to their new markets. To have strategic installations, infrastructure,” he said.

On Friday, worried Faafu locals mounted a protest on the island of Biledhdhoo, under a heavy police presence. Earlier in the week, the Maldives Independent reported that two of its journalists in the atoll had been detained overnight by police.

Maldives police had issued a written warning against any demonstration that might embarrass a visiting foreign leader. Saudi king Salman bin Abdulaziz and his entourage are set to spend two weeks in the Maldives at the end of March, as part of a tour of Asia.

People of Faafu Biledhoo protesting against sale of faafu atoll to the Saudi King. #SaveFaafu pic.twitter.com/h1JvsoORAx

— Shauna Aminath (@anuahsa) March 3, 2017

Ahead of #Saudi King Salman visit, #Maldives police warns strongly against any/all forms of expression that may ‘belittle’ visiting leaders https://t.co/o40Fb1RXyS

— AzraNaseem (@Manje) March 1, 2017

At a briefing for international journalists in Malé, housing minister Mohamed Muizzu said he hoped it would be a big investment: “We don’t want to move slowly; we want transformational change. That is the whole mentality of this government. We want to bring better living conditions to this country on a large scale, in a small period of time.”

Protests against the deal were “not in the best interests of the country,” he added. “A responsible opposition would always give support to the government and the people for whatever project that is beneficial to the country. That has been the case in all the other democracies as well.”

Opposition MP Eva Abdulla – a cousin of Nasheed – told Climate Home: “With Faafu or any other project, we are told there will be a trickle-down effect. That is not what we have seen. It is government MPs and their cronies who get all the benefits.”

Nasheed was the nation’s first democratically-elected president and was removed in what his supporters describe as a “coup” in 2012. He now lives in exile in London, where he met Climate Home at a hotel restaurant.

He said scholarship programmes for young islanders to study in Medina or Mecca have facilitated the spread of Wahhabism, the founding faith of the Saud dynasty. This cultural campaign laid the groundwork for an “unprecedented” land grab.

The view from Malé

At the city beach on Saturday, children splash about in a small enclosed section of lagoon. Mohamed is with his wife and sister-in-law, who retreat to a bench five metres away when asked questions.

A member of the Maldives military, Mohamed asks not to use his full name because he has seen people lose their jobs for criticising the government. A wrong word could also jeopardise his chances of getting a new apartment in Hulhumale, the reclaimed island next to the airport.

“In my opinion, that is not good to give too much long term… it is the Maldivian property,” he says of the rumoured Faafu atoll sale.

Roughly half the population of the Maldives lives on tiny, overcrowded Malé. (Photo: Shahee Ilyas)

He describes approvingly a shift towards conservative Islam in recent years. “Mixed dancing with short clothes” is no longer accepted. “If it is in resorts then it will go well, [but] normal people cannot see that… Little boys and girls, they get a bad image.”

One of his wife’s sisters got a scholarship to study business administration in Saudi Arabia and religious experts visited during Ramadan, the holy month of fasting.

“Nowadays, people are well educated, many religious people are there and because of this, people know what is in the religion. When I was my son’s age, I don’t know what is religion, I just follow my mum and dad.”

Khathma, a school teacher visiting Malé for the weekend from Himmafushi, 17km away, has heard about protests on Faafu even though they were not on the TV news. “It is not a good thing, right, because that is our islands, Maldives islands,” she says.

Not everybody opposes the deal. Firushan and Fathun sit toying with their smartphones under a palm tree. They met on Facebook and hope to get married soon.

Firushan does not like overcrowded Malé, where he shares a small room with a friend – “it is a bad dream” – but has been obliged to come here for rehabilitation from a marijuana habit. They will stay until Fathun has completed her training to be a nursery school teacher.

A billboard, featuring president Yameen, advertises the government’s green development plans. (Photo: Megan Darby)

He points at the China-Maldives “Friendship Bridge”, one of the biggest infrastructure investments in the country. “We have seen it, it is a good investment here, so I guess as well it [the Saudi investment] is a positive…

“I don’t see any harm in it. If the country goes forward, then everybody should be happy. If my islands are getting that kind of investment, I would appreciate it. Every atoll is competing with Malé.”

In the fish market, standing over a slab of gleaming local tuna, Adnan Siraj says he trusts president Yameen to get a good deal for the Maldives. He speaks in Dhivedi and Moussa Afeef, a self-appointed guide who runs a nearby souvenir shop, translates.

Dried fish seller Abdulla Youssef shakes his head emphatically when asked about the Saudis. “I don’t like,” he says in English. He has nothing against the people – good Muslims – but is not happy about ceding territory to foreigners.

Ibrahim Thoufeg, who sells sweet potatoes and carrots imported from Sri Lanka as well as Maldivian bananas and chili peppers, takes a similar view. “Saudi is good, the country is good,” interprets Afeef, but “he is not really happy to sell to any other countries these islands.”

“[The Saudis] have had a good run of propagating their worldview to the people of the Maldives and they’ve done that for the last three decades. They’ve now, I think, come to view that they have enough sympathy for them to get a foothold,” said Nasheed.

In February, the Saudi embassy in Malé was criticised for handing out sealed envelopes filled with cash to local Maldivian journalists at an event. The embassy described them as “gifts”. On Saturday, it was reported that the Saudi national airline was doubling the number of flights from the kingdom to Malé.

Foreign land ownership was illegal in the Maldives until 2015, when the Yameen government passed an amendment to the constitution. Nasheed compared Saudi acquisition of Faafu to China’s building of military facilities on islands in the South China sea.

“This is far more devious, because they hide inside you and they come out when they want to,” he said.

In exile: former Maldives president Mohamed Nasheed sought asylum in London after he was allowed to leave prison in the Maldives to receive medical treatment. (Photo: Karl Mathiesen)

Dr Theodore Karasik, senior advisor to Gulf States Analytics in Washington DC said the motivation for the Saudis was unlikely to be militaristic.

“Saudis are not going to set up bases anywhere else. Saudi uses allies and proxies to try to achieve strategic and tactical goals… [Their intention is] to build up a network of allies that form a logistical chain from the Gulf to east Asia and back,” he said.

US imports of Saudi oil have steadily declined since a 2003 peak, falling 40%. Growing demand in China offers a new opportunity for the kingdom. But it is not without competition. In 2016, Saudi Arabia was overtaken by Russia as China’s largest source of oil.

Last year, the kingdom unveiled an economic restructuring plan called “Vision 2030” that points towards deeper economic ties with east Asia. Karasik says the Indian Ocean supply chain is “absolutely critical” to the success of the plan.

King Salman is on a tour of the countries along that supply chain, striking deals and announcing investments in Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, Japan, China and finally the Maldives.

“Saudi partnership with other countries will be required to ensure that freedom of navigation remains and that piracy and terrorism doesn’t occur,” said Karasik.

Saudi Arabian King Salman bin Abdulaziz (Photo: Erin A. Kirk-Cuomo)

The employment of the Maldives as a strategic anchor for future oil trade rubs against the country’s vulnerability to climate change. It is the lowest-lying country on earth, with a high point of just 2.4m, meaning even small rises in sea level could be devastating. (Nasheed rose to international prominence for his advocacy on the issue as president.)

According to the International Energy Agency, oil demand in China must peak within a decade for the 2C temperature goal of the Paris climate agreement to be met – even more radical cuts will be required for survival of communities in the Maldives according to the government’s own statements.

Though the physics of climate change are inexorable, geopolitical forces are also overwhelming these islands. In August 2015, Salman and Chinese premier Xi Jinping signed a cooperative agreement on China’s One Belt, One Road initiative – the cumulative term for the New Silk Road and the Maritime Silk Road that China has outlined as its key strategic supply lanes (see figure below).

This has coincided with a widening of Chinese interests in the Maldives. The Chinese premier, Xi Jinping visited the islands in 2014, announcing the construction of a US$210 million “Friendship Bridge” connecting Malé to its airport island. China is also financing an extra runway at the airport and intends to develop a port on Laamu atoll, which lies south of Faafu. The Maldives, once tied to India for its economic survival now owes 70% of its external debt to China.

Chinese-owned or financed port locations (existing and proposed) along the Maritime Silk Road. Maldives marked with red rectangle. (Source: Institute for the Analysis of Global Security)

Cleo Paskal, associate fellow at Chatham House and author of Global Warring: How Environmental, Economic, and Political Crises Will Redraw the World Map, said the Saudi purchase of Faafu could lay the foundation for China to extend its military reach in the Indian Ocean, securing Saudi and Chinese interests.

“China is on record as wanting a base in the Maldives,” she said. “It was a big issue in 2015. It already has or is working on ‘commercial’ ports in several countries along the route from the Indian Ocean to China and recently opened an overtly military naval base in Djibouti. Saudis are unlikely to build anything like that for themselves, but may facilitate the construction of some sort of ‘resupply’ installation built by China that would likely have dual use capacity.”

She said this would raise concerns in Delhi, which has courted its neighbours. It would also place the Chinese military very close to the US base at Diego Garcia. The US state department did not respond to requests for comment.

Ankit Panda, senior editor of The Diplomat, cautioned against ascribing long term strategic motivations to the Faafu deal – should it eventuate. He said the purchase was clearly part of the Saudi programme to diversify its economy from oil, but that the Maldives may be playing a longer game.

“The geopolitical layer to this, in my view, is more on the Maldivian side for now. The Saudis are looking primarily for a strategic investment opportunity,” said Panda. “The [Maldives’] leadership understands its strategic location in the Indian Ocean and sees a Saudi outpost there potentially paying dividends in the future.”

It was also likely, said Karasik, that the Saudi visit would be accompanied by the announcement of an investment in the country’s newly-created national oil company, MNOC. A UK company, Zebra Data Sciences, has been linked to further exploration after the government announced that initial prospecting had found deposits of oil and gas in the atolls.

Energy and environment minister Thoriq Ibrahim told Climate Home: “What the country needs now is to use the resources we have. We don’t know yet [whether there are viable oil reserves]. There was a research team here.”

All of this investment, said former president Nasheed, was happening without transparency. This was particularly problematic given the Yameen government’s history of corruption. Last year, an Al Jazeera documentary revealed a land deals racket that saw cash from foreign buyers going missing – some of it ending up in Yameen’s personal bank account.

“One of the issues with these kind of hidden deals is that it encourages corruption and through corruption you can subvert states… This is fairly unclear territory we are going into,” said Nasheed.

Megan Darby’s travel to the Maldives and accommodation was paid for by the Maldives government.

Note: an amendment was made to correct the date of the end of Nasheed’s presidency and to clarify Eva Abdulla’s familial relationship to Nasheed. A quote from Muizzu was extended to reflect that he felt the opposition should support the interests of the country.