When Cyclone Aila hit the coast of Bangladesh in May 2009, water swelled over embankments along the Kholpetua river.

The home Sirajul Islam (pictured) shared with his wife and four children in Kolbari village was flooded, along with the single acre he used to raise shrimp.

The home Sirajul Islam (pictured) shared with his wife and four children in Kolbari village was flooded, along with the single acre he used to raise shrimp.

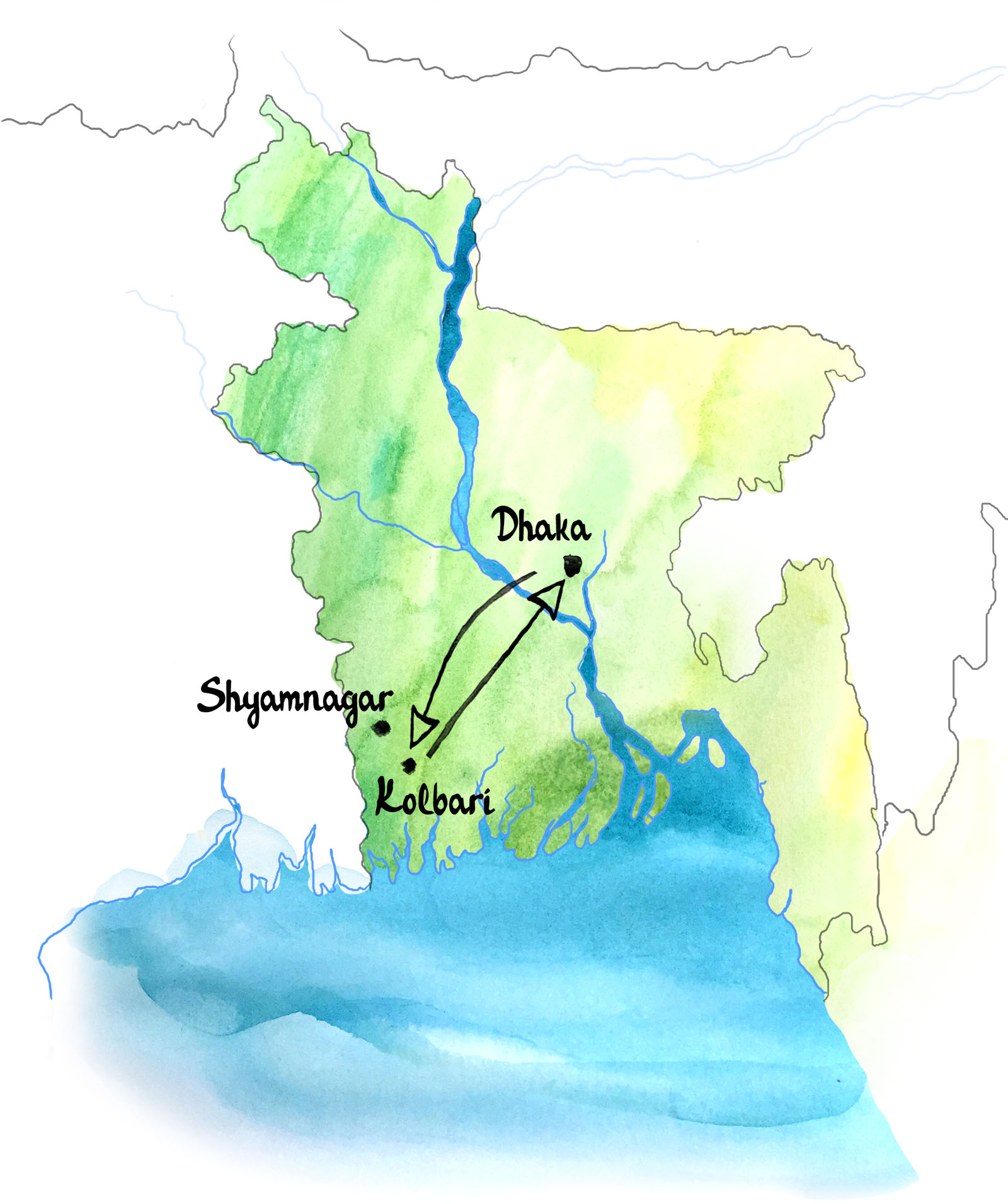

They left for Shyamnagar town, 15km away, where for four months he made 300-400 taka a day ($4-5) driving a rented motorbike.

When the floodwater subsided, his field was too salty for shrimp. Village buildings were flattened and there was no fresh water to drink. So in 2011, the family went to seek their fortune in the capital Dhaka.

“The cyclone had broken my economical backbone by destroying everything,” says Islam. “If there had not been such a big cyclone, I would not have moved to Dhaka.”

Bangladesh’s prime minister Sheikh Hasina has told the UN that a one-metre rise in sea level – a plausible scenario this century – would submerge a fifth of the country and turn 30 million people into “climate migrants”.

Islam shows off a set of deer antlers, a trophy from hunting in the Sundarbans, across the river. Most of the household income is from selling fish, crab and honey gathered in the mangroves – supplemented from his eldest daughter’s wages at a garment factory in Chittagong.

If there were to be another cyclone, Islam says “I would fight” to stay. It is not likely to get any easier, though. Sea levels are set to rise, compounding the problem of salt intrusion into groundwater. Tropical cyclones are expected to get more intense and destructive with global warming. In combination, they raise the risk of another devastating storm surge.

Dislocation: Sirajul Islam and his family left home for five years after Cyclone Aila destroyed his coastal livelihood

Over the past two decades, Bangladesh’s rural population has been pouring into its cities. A 2014 slum census found the number of people living on the margins of cities had doubled to 2.2 million since 1997. Meanwhile, the population in southwestern coastal regions is stagnating.

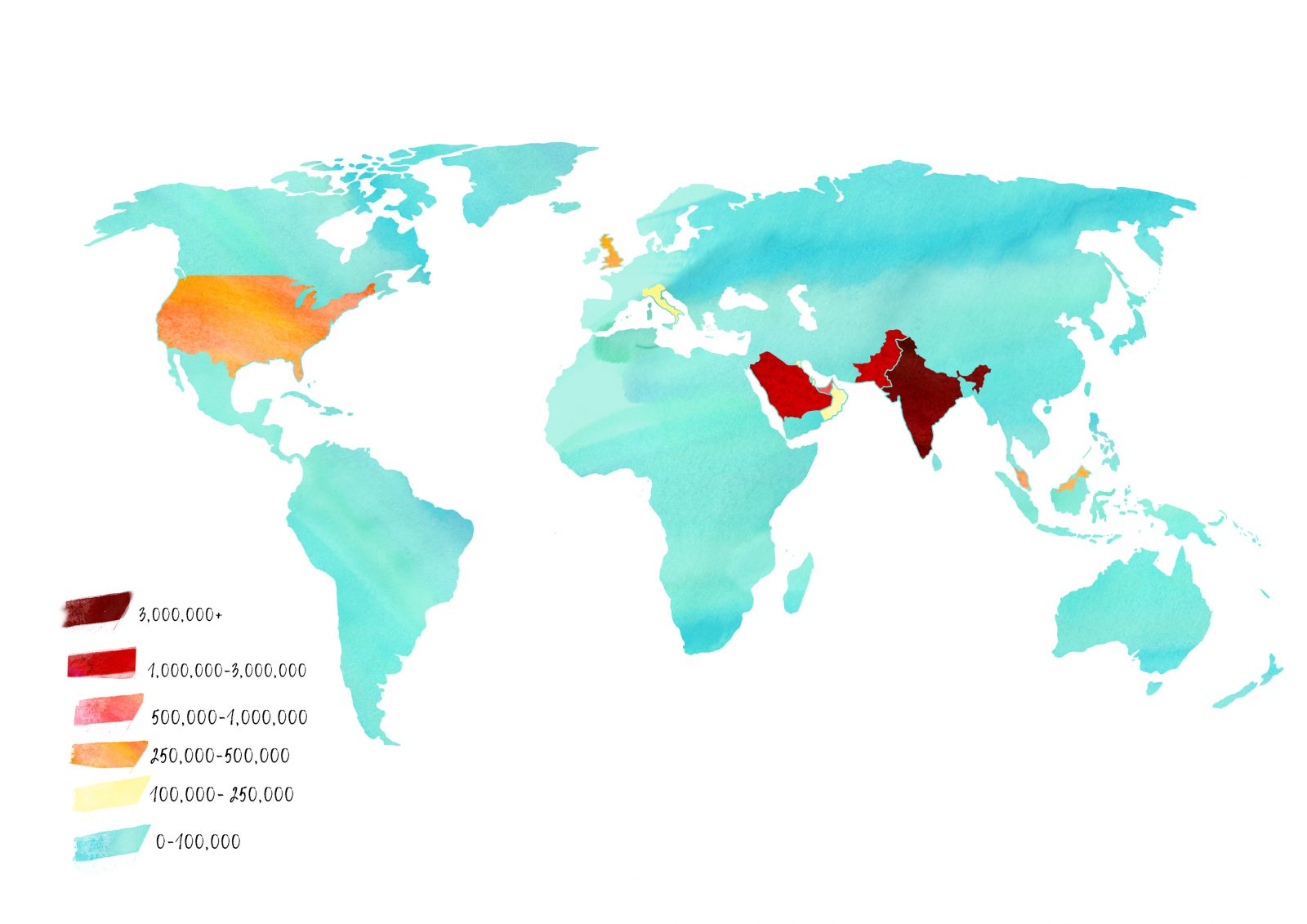

A smaller, but significant, number of displaced people cross borders, which is where it becomes a matter of at least regional, if not international concern. Up to 20 million Bangladeshis are said to be living illegally in neighbouring India. A militarised fence along 70% of the 4,000 kilometre frontier sends an unwelcoming signal. Still, people find ways to evade the patrols, typically by boat across the rivers.

Zainab Begum (pictured), a 40-year old woman collecting water from Gabura village pond, across the river from Kolbari, has two younger sisters working as waste pickers in Tamil Nadu, a southern Indian state.

Zainab Begum (pictured), a 40-year old woman collecting water from Gabura village pond, across the river from Kolbari, has two younger sisters working as waste pickers in Tamil Nadu, a southern Indian state.

With their families, they have crossed the border illegally several times. It is a risky business: one got caught and was badly beaten by Indian border guards, detained for a week before she could bribe her way out.

There was little to keep them in Gabura, one of the worst hit areas by Aila. Not a single house was left standing, says Begum, a fierce note in her voice. The levee that was supposed to keep the river out trapped a layer of sludgy, salty water on the land for three whole years. She lived in a makeshift house on the embankment; others with more resources left permanently.

Eventually, the government helped them rebuild. A three-storey cyclone shelter stands proud at the heart of the village. But land that was previously good for one rice crop a year became too salty: now it is all shrimp.

In this battered economy, Ziaur Rahman is trying to make a living teaching English and maths to private students. With a degree from Khulna University, he shows more awareness than most about the global trends affecting his country. He tells Climate Home in English: “I know about climate change. When climate change in this place, we are not happy.”

The outlook is not all bleak. Just as farmers adapted to fattening shrimp, now some have turned to crab, which can tolerate higher salinity. They do not eat it round here: it is “haram” (forbidden) for the Muslim majority and at 250 taka ($3) apiece in the market, beyond most budgets. But there is strong demand from China and Malaysia. A small plant in Kolbari packs the shellfish for export.

The scale of migration from vulnerable areas will depend on the success of these adaptations, as well as the severity of climate change impacts.

Nazzma Begum came from Bhola, on the coast, as an 18-month-old baby. Now 32 and a widow, Dhaka is her only home: her parents lost everything to river erosion. She shares a single room with her two children in the generically named “boat ghat” slum and makes a living cooking and cleaning for wealthier families.

Nazzma Begum came from Bhola, on the coast, as an 18-month-old baby. Now 32 and a widow, Dhaka is her only home: her parents lost everything to river erosion. She shares a single room with her two children in the generically named “boat ghat” slum and makes a living cooking and cleaning for wealthier families. Catching a plane to a wealthier nation is an outrageously expensive gamble. For every success story, there are cautionary tales of exploitation.

Catching a plane to a wealthier nation is an outrageously expensive gamble. For every success story, there are cautionary tales of exploitation.

myriad smaller crises.

myriad smaller crises. “Khulna is one of the most vulnerable cities in Asia,” says Moni. “This is because of climate change. Fifty years ago, the situation was not like this but now it is changed.”

“Khulna is one of the most vulnerable cities in Asia,” says Moni. “This is because of climate change. Fifty years ago, the situation was not like this but now it is changed.”