UN climate talks this fortnight could determine whether a post-Trump US president would rejoin the Paris Agreement, according to two former top Obama officials.

At discussions in Katowice, Poland, almost 200 countries will try to agree the Paris Agreement ‘rulebook’. That should lay out how countries will enact the accord, for example how they report their efforts to fight climate change. But as talks began on Sunday, thousands of points of disagreement remained.

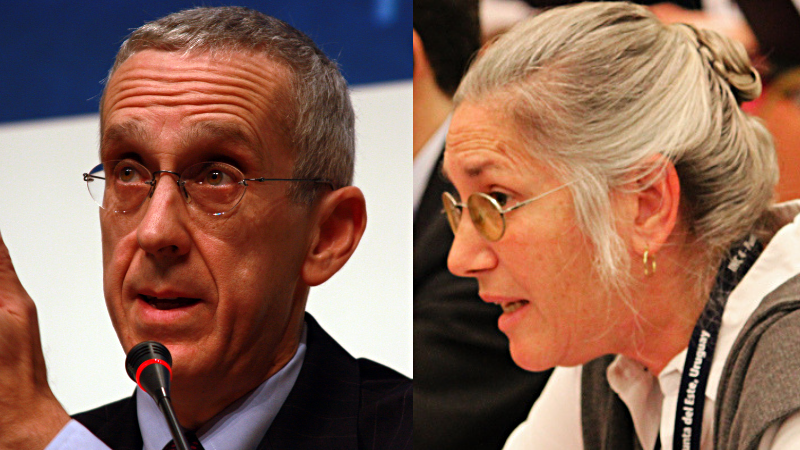

Todd Stern and Sue Biniaz, the lead climate envoy and lawyer in Barack Obama’s state department and key scribes and agents of the 2015 Paris deal, spoke to Climate Home News.

Biniaz said: “Some countries, and I’m not exactly sure exactly who’s in this camp, are, I would say ignoring the language of the Paris Agreement and basically saying there should be two different sets of guidelines: one for developed countries and one for developing countries. I would say that that’s just completely inconsistent with what was agreed in Paris.”

All the Cop24 news in your inbox? Sign up here

A hard divide between developed and developing nations would allow China, India, other major polluters and many middle income countries to slip into a category where the Paris Agreement has softer requirements.

That will be resisted by the US administration under Donald Trump. But yoking China to the same climate regime as the US has been a bipartisan policy in Washington for decades. Therefore, it could also be unacceptable to a future Democratic president, according to Biniaz and Stern, who have left the US government and are now working in Washington DC think tanks, but continue to participate informally at UN talks.

“I would hope, just as a person who thinks that the Paris Agreement is a good thing for the United States to be a part of, that whatever rulebook comes out would be considered acceptable to a future administration that would want to rejoin the agreement,” Biniaz said.

Insiders told CHN China was driving the push by recruiting proxies to suggest amendments to the text. Biniaz was also the top lawyer for the Bush administration when it pulled back from the Kyoto Protocol because it did not place restrictions on China and other big emerging polluters.

“I think that if the balance were off – like it went backwards on issues of differentiation – that future administrations might look at that and say ‘that’s not really something we want to be a part of’,” she said.

CopCast: Episode one

– What are we doing in Katowice?

Throughout the next two weeks, we’ll be starting the morning with the news that is driving the day and guests to explain what is happening inside the room and out of it.

Sara Stefanini and Karl Mathiesen caught up on Sunday evening for our very first episode. Follow us on Soundcloud and please share, share, share!

Stern said he could not predict the policy of any future Democratic leader. But, he said, “I’m a Democrat and I come at climate change from that perspective.”

Stern, who is now a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, has raised concerns about placing a “firewall” between rich and poor countries.

“I think [people] probably can draw the conclusion [that] if Stern’s got a big problem with it, that might lead us to think that some future administration would,” he said.

Both Stern and Biniaz said the Paris Agreement already allowed for “flexibility” for developing countries when they could not meet the requirements of the common set of rules. Stern said this “supple” means of differentiation was one of the major advances of the Paris deal.

Stern added, it was “not a very appealing argument” to ask other countries to push for a certain outcome in Katowice in order to keep the door open for a future president, “because the US has walked away… in a very disruptive and aggravating manner in the eyes of virtually any other country you can think of”.

Manuel Pulgar Vidal, who was the president of the 2014 Lima climate talks and is now climate lead at WWF, said trying to predict the US position under a future president was inadvisable. “If we are going to take decisions based on the political context, we could fail,” he said.

The binary option can be seen throughout the hundreds of pages presented to diplomats before the talks. For example, the section on transparent reporting of emissions cuts contains three options: common rules, partially different rules and completely separate sets of guidelines for rich and poor.

Some observers CHN spoke to believed efforts to push a binary system were tactical, and were likely to soften at these talks.

Biniaz said she was “pretty confident it’s not going to come out that way”. Pulgar Vidal was less certain, adding that it was “the most contentious topic” at the talks.

Know your NDCs from your LMDCs: A climate diplomacy glossary

The issue is likely to result in significant tensions between the US and Chinese delegations at the talks in Katowice. A state department spokesperson said that although the Trump administration expected to withdraw from the deal in 2020, it continued to participate in discussions to “ensure a level playing field”. In November, a US state department team travelled to Beijing to try and find common ground ahead of the talks.

Li Shuo, a policy advisor for Greenpeace East Asia, said China had to walk a fine line, because a collapse in the talks would add to the list of issues over which China is currently at odds with the West.

“It’s not in China’s interest to have another battlefield, a battlefield where China has actually performed quite well over the past years,” he said. The Chinese government did not respond to questions.

China will be represented in Katowice by its long time climate lead and former minister Xie Zhenhua. The US delegation will be led by Judith Garber a deputy assistant secretary, three rungs below ministerial level. Li said Xie’s efforts to move forward on political questions had been “frustrated” by the Trump administration’s lack of a political lead on climate change.

Stern, who since he left the government has held informal meetings with Xie, said there was a danger of the talks going off track because the US was “not engaged at a political level”.

“It’s not like there are other people at a senior level expressing the kind of views that I would want to get across, because that’s not the case. So yes, I decided to get more involved myself but for the sake of the agreement, not on behalf of the United States,” he said.