In the Arctic something odd is taking place. Temperatures in Spitzbergen, on the Norwegian island of Svalbard, hit a balmy 4C on Monday,

At this time of year they should be around minus 16C. Instead locals are having to adapt to a fast-changing environment, one that leaves Norway’s environment minister Vidar Helgesen in a sweat.

“What is happening now is a harbinger of things to come, we are seeing drastic changes,” he tells Climate Home in an interview.

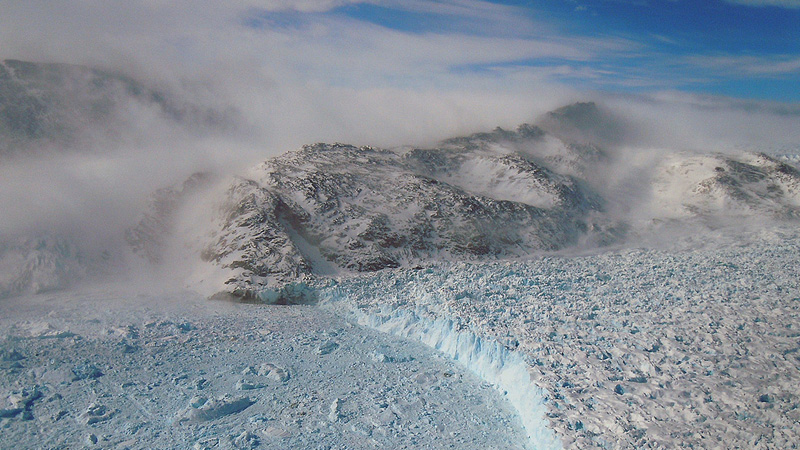

“One of our major glaciers is retreating one metre a day, two kilometres in five years. It’s happening very fast and the world should take note.

“This will happen faster in the Arctic. We know a 2C rise in global average temperatures means up to 4C in the Arctic.”

The unusual conditions should alarm all governments, he says, given the Arctic’s influence on global weather patterns and the evolving links between climate change and issues such as conflict and migration.

For the third time this winter, the North Pole may hit the melting point this wk. Explainer: https://t.co/Z6rvybuGM1 pic.twitter.com/YyTze6Ntih

— Andrew Freedman (@afreedma) February 6, 2017

With around 10% of Norway’s population living within the Arctic circle, climate change is a live issue for politicians in Oslo.

On land, residents face melting permafrost and unusual temperatures impacting agriculture. At sea diminishing Arctic ice opens up the country’s seas to foreign trawlers and Russian warships.

“Traditionally we have viewed the Arctic through an economic and security angle. Most of our ocean territory is in the Arctic and we have a history of harvesting the oceans,” says Helgesen.

“Since the end of the cold war we have seen gradually more economic attention, but now evidently security is back as a major issue.”

2016: record low amounts of sea ice, particularly in the Arctic pic.twitter.com/DHH7NT2cFh

— Ed Hawkins (@ed_hawkins) January 18, 2017

By security he means Russia – the hulking colossus that Norway shares an Arctic border with.

Bodø Air Station is one of NATO’s frontline bases facing off Moscow: Norwegian jets routinely shadow Russian bombers as they test the alliance’s defences.

At sea, Russia plans to build three new icebreakers, Reuters reported last month, as Arctic sea routes become more accessible.

Old Soviet bases are being reactivated, radar equipment and anti-aircraft missiles are being upgraded.

Last week the US military revealed the levels of its concern with the publication of a 16-page Arctic strategy, urging more investment in military hardware and training.

Pentagon: Arctic melt requires updated US strategy https://t.co/Rlsdbcr6sA pic.twitter.com/ybPdMaiFsZ

— Climate Home News (@ClimateHome) February 3, 2017

One concern is that as the ice melts, historic claims from Russia, Canada and the US together with other Arctic nations on portions of the oil and mineral-rich ocean will cause friction.

“In the mid- to far- term, as ice recedes and resource extraction technology improves, competition for economic advantage and a desire to exert influence over an area of increasing geostrategic importance could lead to increased tension,” reads the US strategy document.

Another worry is that ice-free routes will see a surge in shipping. According to the UN’s IPCC climate science panel Arctic shipping lanes could be open for four months a year by 2050. There are already signs of an uptick in traffic.

Norway is taking action; buying fighter jets, patrol aircraft and submarines and has banned the use of heavy fuel oil near its Arctic coastlines.

Despite signs Donald Trump wants to pull the US back from the multilateral arena, Helgesen is confident the Arctic Council – a forum bringing together 8 nations with Arctic interests – can resolve any disputes.

Barack Obama’s Arctic envoy Admiral Papp is no more, but Helgesen hopes to meet his replacement soon to ensure “stable cooperation” with Washington continues.

Senior US officials pledged continued support at last month’s Arctic Frontiers Conference, he says, stressing there is “no change in direction” as far as he can see from the new administration.

“Even through the Cold War we had well functioning arrangements with the Soviet Union on fishing,” Helgesen adds.