“It is a miracle.” That is UN shipping chief Kitack Lim’s view of progress on talks in the last few years to cut the sector’s carbon footprint.

Speaking at an industry conference in London on Wednesday, he said members of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) were “getting closer” to agreement on the way forward.

“Next year really will be a time when the world will expect the IMO member states to deliver a vision, as a first stage in the IMO roadmap,” Lim said.

The UN body has three weeks of negotiations scheduled before its deadline for producing an interim climate strategy in 2018. A working group on the issue met for the first time in July.

Climate Weekly: Sign up for your essential climate news update

In the first panel of the day, industry chiefs showed more engagement with the subject than in previous years, but remained wary of committing to significant carbon cuts.

Esben Poulsson, chair of the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS), said: “There is no doubt that CO2 is the big one now. At the ICS board, we spend a lot of time every meeting on this.”

Since an overwhelming majority of countries agreed to address greenhouse gas emissions within their borders under the Paris Agreement in 2015, international transport has been under pressure to do its bit.

In the IMO, a number of European and island states have been pushing for an ambitious emissions target. Without curbs, the industry predicts shipping emissions will grow 50-250% by 2050, in tandem with an increase in seaborne trade.

“We absolutely do need targets,” said Magda Kopczynska, director of maritime transport at the European Commission’s transport department. “We have to decide now what we are going to do; we can’t say: we will do something in 2030.”

Emerging economies, major flag states and industry voices are arguing against an absolute emissions cap, however, on the basis that it could constrict economic development.

As a compromise, four trade associations responsible for 90% of global trade have proposed cutting the intensity, rather than total, of their emissions in half by 2050. But climate analysts say the sector must improve efficiency 60-90% in that time to be in line with cut that would keep global temperature rise below 2C. To stay within the tougher 1.5C warming limit demanded by climate vulnerable communities, it must go carbon neutral.

Cutting emissions will require not only more fuel efficient components but a shift to run on hydrogen, biofuel or electric batteries. Slower speeds also make a big difference to fuel consumption.

“It is a huge challenge and one that is going to require everyone at the IMO to lift their game dramatically,” said John Maggs, campaigner with the Clean Shipping Coalition.

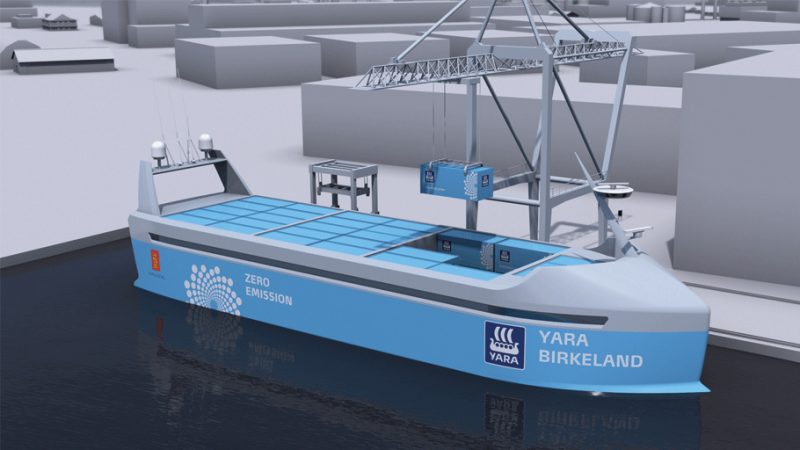

The first demonstration projects for zero carbon shipping are emerging, however. The world’s first electric car ferry is operating in Norway and technology firm Kongsberg Gruppe has announced plans to float a zero emissions container ship next year.

Sveinung Oftedal, official from Norway’s environment ministry and chair of the IMO working group, struck an upbeat note: “The solutions for emissions cuts are also growing and the willingness to take real action is more firm.”