This week, the 2020 UN climate change conference was postponed. Last week, the UN biodiversity conference was likewise put on hold. These decisions are disappointing: everyone expected 2020 to be an important year for environmental decision-making processes.

My colleagues and I recently wrote about our high hopes for 2020 to revive the momentum lost in 2019. But those hopes were penned weeks ago, before the deadly spread of coronavirus. The pandemic has disrupted everything.

These decisions to delay are the right ones, to protect public health and to ensure equity in environmental governance.

Gathering thousands of people from across the world into close quarters for two weeks during a pandemic before sending them back across the planet would risk lives.

Until coronavirus is under control, such Conferences of the Parties – Cops – risk becoming super-spreader events.

It is fair to worry these postponements mean delayed action on climate and biodiversity challenges. Some recent developments haven’t been encouraging.

Cop26 climate talks postponed to 2021 amid coronavirus pandemic

The Paris Agreement is due for its first major review this year, but few countries have updated their 2015 pledges to turn aspiration to climate action. Norway and Japan are the only developed countries to put forward new pledges. The 2019 Madrid climate change conference left many worried about the future of climate action under the UN system.

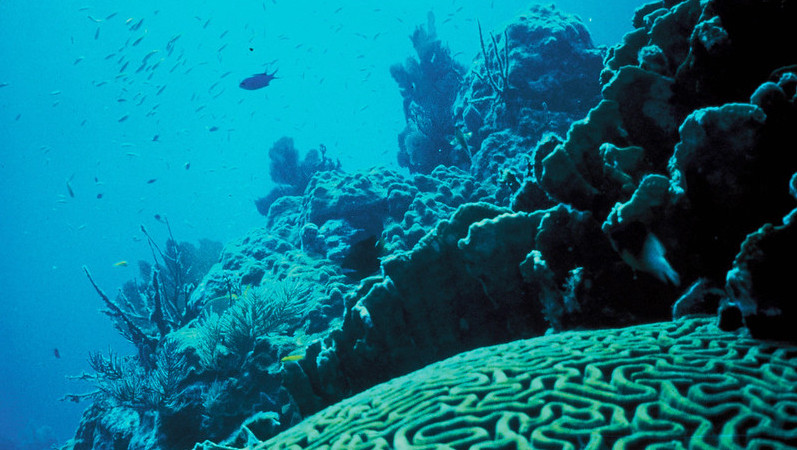

Biodiversity was to have a ‘super year’ in 2020. Delegates launched discussions on a post-2020 global biodiversity framework to follow up the 20 Aichi Biodiversity Targets. The working group negotiating these new targets squeezed in a meeting this year, pre-coronavirus.

While negotiators agreed the “zero draft” was a good start, it was clear much work remains to reach agreement on a new approach to protecting nature.

But there is movement on these issues in the midst of this crisis. The EU and other countries are already considering how their post-Covid responses can fuel a just transition to a low-carbon world.

China’s ban on consuming wild animals explicitly acknowledges our destruction of the natural world is partly what led to this pandemic.

We’re sharing stories of wildlife reclaiming streets and of cleaner waters and air, and people seem to have a new-found appreciation for nature. As the conferences reschedule, they can try to seize the momentum of these tangible changes.

On the diplomatic side, there is extra time to pre-resolve potentially contentious issues in the post-2020 global biodiversity framework or to find traction for global climate action.

While the world is on various levels of lockdown, virtual discussions among diplomats can continue.

The incoming UK presidency for the climate summit can try to find a way to signal renewed momentum toward tangible climate action, in lieu of new pledges. The incoming Chinese Cop president for the biodiversity summit can use this additional time to discuss difficult issues with interested parties and smooth the negotiations ahead.

Such efforts put considerable pressure on the incoming presidencies to ensure transparency.

Back room chats and informal one-on-ones are normal – this is diplomacy, after all – but there is usually a mechanism to keep all countries informed.

During the Paris climate change conference, the French presidency held daily meetings with every coalition and some individual countries during the day and convened large, open invitation meetings in the evening. These were in person.

Zoom climate diplomacy: ‘Technology doesn’t help build trust’

The British and Chinese incoming Cop presidencies will have to innovate with a virtual format. To uphold transparency, they must find a way to keep countries informed and, crucially, engaged. Transparency is now more crucial than ever: who receives the Zoom invite has the key to global governance and those without are left on the margins.

A lack of transparency strongly contributes to a lack of equity in global environmental governance.

The powerful cannot make decisions for those with fewer resources to juggle a pandemic response and environmental action. When such inequities are apparent, negotiations break down.

When developing countries’ right to be involved is tossed aside, they can block the solutions powerful countries provide. We saw this at the Copenhagen climate change conference in 2009, when a few developing countries refused to adopt the Copenhagen Accord after being excluded from the discussions.

Postponing the 2020 climate and biodiversity conference means developing countries will have a say in global responses to climate and biodiversity crises.

The Coronavirus pandemic has yet to spread in some developing countries: they will face the onslaught later, when some of the meetings were originally to convene. International flights are already becoming rare and expensive.

Going ahead with these meetings would have excluded many voices, putting the legitimacy of any decisions on shaky ground.

Global environmental governance is for all. Some countries have greater responsibilities for the problems and others disproportionately experience the negative effects of ecosystem degradation and climate change. All must be part of the solution, or solutions will be fundamentally unsound.

Dr Jen Allan is lecturer at Cardiff University & team leader at Earth Negotiations Bulletin / IISD