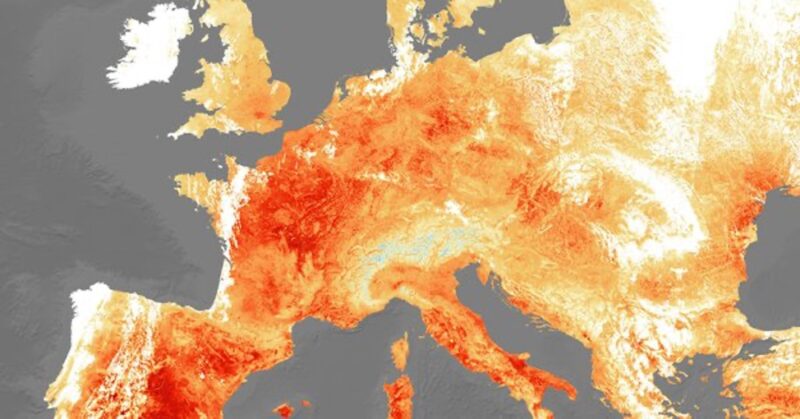

July 2021 was the hottest month on Earth since observations began, as countries across the globe broke yet more temperature records.

Above average conditions were seen on every continent and findings were made possible through the analysis and comparison of various data readings using a number of different methods, including satellite imagery.

To analyse temperature, many datasets take physically recorded measurements from meteorological stations and then use spatial interpolation to obtain a bigger picture look at heat over a regional area. This technique utilises values at known points to estimate values at unknown points, so brings with it a degree of uncertainty, particularly in areas with low station distribution, as the method is based on probability.

Readings from satellite data, however, take multiple readings across the Earth’s surface and are therefore often considered to be a more accurate way to record and understand global and regional temperature variability and the underlying physics associated with it.

The European Space Agency are currently developing technologies to analyse temperature using satellite measurements as part of its Climate Change Initiative Land Surface Temperature project. This is aided by the Sentinel series, a family of missions developed by the agency as part of the European Union’s Earth observation programme, Copernicus.

The aim of the ongoing work is to be able to detect smaller changes in the climate with greater confidence which will help further understand and predict heatwaves, drought and fires.

Dr Darren Ghent, who is the Science Lead on the project, said “Satellite observations of land surface temperatures, and their change, are increasingly recognised as being able to provide unique and detailed knowledge to better facilitate the understanding of climate change”.

Copernicus Sentinel 3’s Sea and Land Surface Temperature Radiometer, for example, generated maps of Turkey and Cyprus during extreme heatwaves experienced in August of this year. While weather forecasts used predicted air temperatures, the instruments on board the Sentinel measured real time energy radiating from the land, which allowed for more accurate forecasting of temperature in the region.

The latest in development is the Land Surface Temperature Monitoring (LSTM) mission, or Sentinel-8, which will carry a high spatial-temporal resolution thermal infrared sensor to specifically provide observations on land-surface temperature.

In low-Earth polar orbit, the satellite would also map rates of evapotranspiration at resolution of 50 metres, 20 times finer than its predecessors like the radiometer on Sentinel-3.

“In an urban context, this will help to understand and model thermal activity and ventilation in and around individual cities and inform planning and ‘climate-adaptive’ building design to deal with heatwaves such as those experienced in western Europe during June,” said Ghent.

“The data, however, will be equally, if not more relevant, in a rural setting, with major benefits relating to food production and sustainable water use,” Ghent continued, “at the expected resolution it will be possible to monitor the temperature of individual fields, enabling growers to tailor irrigation regimes to specific crops and locations.”

Test flights are currently being undertaken with an instrument called HyTES (Hyperspectral Thermal Emission Spectrometer) on board a small twin-engine aircraft above rural British and Italian lands. The instrument is an advanced thermal imager built by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, as part of a joint campaign between the American space organisation and ESA.

Ghent concluded by saying “High quality land surface temperature data is integral to food security assessments, is increasingly relevant to crop productivity systems and is essential to forecasting drought. LSTM which is planned to launch in later 2020s promises to deliver significant information sources for commercial services, government policy and citizen information to confront some of the challenges of the next decades.”

Visit ESA’s Climate from Space app to explore global satellite records that span five decades and form a major contribution to the scientific evidence that underpins current understanding and future prediction of the changing climate.

This post was sponsored by the European Space Agency. See our editorial guidelines for what this means.