As 2024 turns to 2025, we asked subscribers to our newsletter what the top climate issues of the upcoming year will be. With climate destruction growing, their responses clearly indicate they want to see more ambition in tackling climate change and more honesty on how climate action is going.

Here’s our summary of responses from our always passionate, well-informed readers and our analysis of when, where and how we can judge whether the powers-that-be are stepping up to the challenge or falling short.

1. Governments must make bigger commitments to cut emissions – and stick to them

Under the 2015 Paris climate agreement, all governments have to submit a climate plan – known as a nationally determined contribution (NDC) – to the United Nations every five years.

The third round of these plans is due next year, ten years on from Paris. Most will add a 2035 emissions reduction aim onto their existing 2030 target and their more long-term goals to reach net zero in 2050, 2060 or 2070.

Several Climate Home readers said NDCs would be a top climate issue for 2025. One said they should be “challenging but realistic” and another said they “must align with actionable policies”.

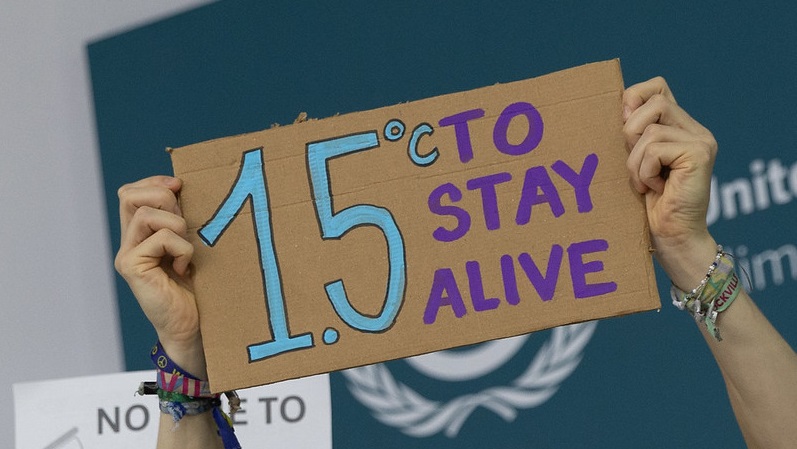

They will certainly have to be more ambitious than the last round five years ago if the world is to stand a chance of limiting global warming to 1.5C or even 2C above pre-industrial levels.

The United Nations said in October that, even if implemented in full, existing NDCs put the world on course for a catastrophic 2.6C of global warming.

2. Governments must prepare for worsening climate change impacts

While the final figures are not out yet, the World Meteorological Organization has said that 2024 looks set to be the hottest year on record. But it may also be the coolest year we see for a while. Even if emissions peak, the world will keep getting hotter until we reach net zero emissions globally.

Climate change worsened dozens of disasters in 2024 from extreme rain in Spain to a heatwave in West Africa and typhoons in the Philippines. The World Weather Attribution group of scientists found that 26 disasters linked to climate change this year killed over 3,700 people and displaced millions.

We’re likely to see more disasters in 2025. One South American reader reported worries about drought, Amazon rainforest fires and rising temperatures while another said “extreme weather patterns demand immediate attention”.

In this context, adapting to climate change is key. At the COP30 climate summit in Belém in November, governments are due to agree on a list of indicators to measure whether and how they are adapting to climate change in areas like water, food and health. The big debate will be whether the provision of finance to developing countries to help them adapt will be one of those indicators.

For the destruction that can’t be adapted to, the new UN loss and damage fund is supposed to help. Its new executive director – Ibrahima Cheikh Diong – hopes to start handing out money to climate victims by the end of 2025 and hire most of its staff in 2026.

A dried out river in Tefé in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest in September 2024 (Photo: Christian Braga/Greenpeace)

3. Nature conservation should pick up pace

Due partly to climate change, species are dying off at a sickening rate. Last year’s biodiversity conference, COP16 in the Colombian city of Cali, planned to address that. While it had some successes – particularly in handing power to Indigenous people – it ran out of time to agree on how to pay for nature protection.

With two years until COP17, governments have agreed to continue COP16 from February 25-27 in Rome. “Securing adequate and predictable financing will be central to our efforts,” said COP16 president Susana Muhamad.

Responses to the Climate Home survey indicate our readers are concerned about nature, both on land and in the oceans where plastic pollution is a particular threat to nature. Talks to set up a UN treaty to tackle plastics failed in Busan in December 2024 but will continue at some point in 2025.

4. We need less misinformation, accounting tricks and jargon

With Donald Trump coming into power as president of the United States, our readers are concerned about misinformation on climate change. Trump has promised to pull his country out of the Paris Agreement, and his often inaccurate criticisms of climate action are likely to influence the public conversation in the US and abroad in 2025.

The United Nations is trying to counter misinformation on climate change with a $10-15 million fund for non-governmental organisations researching the issue and developing communication strategies and public awareness campaigns.

US President-elect Donald Trump (left) is likely to help spread climate disinformation while UN Secretary-General António Guterres (right) has pledged to combat it.

But it’s not just Trump’s claims that worry readers – they also suspect that governments that do recognise climate change are overselling their climate action using accounting tricks.

A Canadian respondent pointed out that the emissions from international aviation are not included in nations’ greenhouse gas inventories and neither are those from forest fires, as these are considered natural and therefore not the government’s responsibility. Meanwhile, Climate Home has highlighted how countries like Guyana use forest carbon accounting techniques to present themselves as carbon negative despite booming oil production.

Another reader criticised the “language barrier” caused by the jargon and acronyms that are common in climate policy. “Bridging the gap between technical acronyms and the lived experiences of skeptics or reluctant individuals is vital,” they said. Another said climate communicators should “avoid masking global warming’s mechanics with unclear terms” and “focus on transparency”.

Will scientists with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change heed this advice as they start writing up a special report on climate change and cities this year?

5. The roll-out of green technology must quicken

Decarbonising the world is going to require a huge variety of technology, and the good news is that the roll-out of green solutions like solar panels and electric vehicles continues to pick up pace every year.

Our readers highlighted technology like heat-pumps, micro-grids and the recycling of aluminium. Other solutions they proposed include city design which encourages walking and public transport, like Utrecht in the Netherlands, and tackling private plane use as “unnecessary luxury emissions”.

All these solutions have restrained the growth in emissions worldwide but have yet to stop them growing completely. Will 2025 be the year in which that changes and we reach peak emissions? It’s possible but by no means certain.

(Reporting by Joe Lo; editing by Megan Rowling)