Yao Zhe is global policy advisor for Greenpeace East Asia.

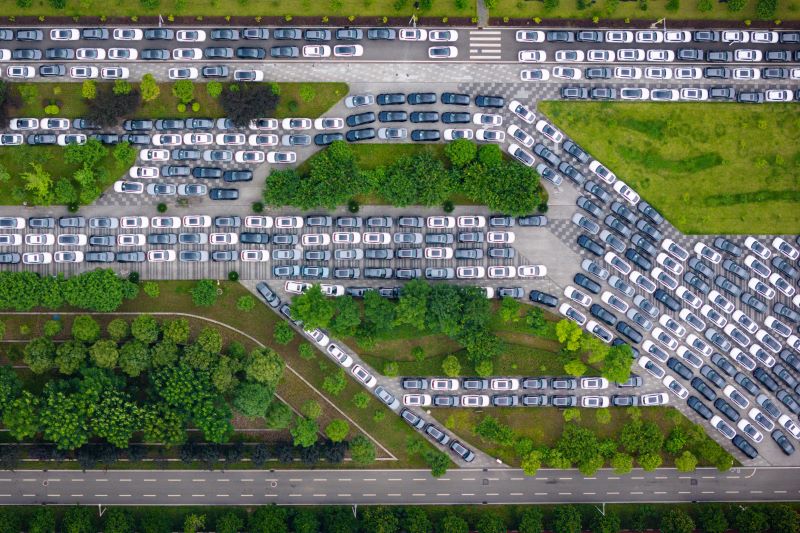

“Overcapacity”, a geeky economic term, has recently become the new buzzword for international discussion around China’s solar and electric vehicle industries. It is also becoming one of the thorniest issues in China’s relations with other major economies.

Notably, the word was mentioned five times in the G7 Leaders Communiqué released last week, with the G7 countries framing it collectively as a global challenge.

It is a debate that was initially sparked by US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen during her April visit to Beijing. According to her, China’s cleantech industry has excess capacities that cannot be absorbed domestically, leading to exports at depressed prices. And she stressed that this should be a concern not only for the US, but also for Europe and other emerging markets.

Days after climate talks, US slaps tariffs on Chinese EVs and solar panels

China strongly disagreed with this claim, while Yellen’s concern resonated in the EU, which has long focused on China’s market dominance. In short, there is an overcapacity of “overcapacities”, with neither side finding identical terms of reference. But as this debate is a harbinger of how climate solutions and political agendas will interweave, it’s worth parsing out some lessons for each side, on their own terms.

The US’ “overcapacity” claim as presented by Yellen is a non-starter in China.

China’s clean energy industry is an important point of pride internationally and a source of legitimacy domestically for Beijing. From that perspective countering the “overcapacity” claim is both emotionally and strategically important.

Strategically, this claim is being used to justify trade measures and tariffs against China’s clean energy products. Emotionally, the cleantech industry is a modern-day success story of China’s entrepreneurship and innovation. In China’s public discourse, the US “overcapacity” claims lands as a rejection of that success.

Lithium tug of war: the US-China rivalry for Argentina’s white gold

The result is a political debate in which – by design – no side can convince the other. And the lesson? This posturing is at odds with US-China climate diplomacy as we’ve known it to function in the past. Whatever objectives this approach serves, it does not include closer climate collaboration between the US and China, even as multilateral climate action at the UN level still requires them to take action in concert.

In China, discussion on “overcapacity” emerged from an ongoing conversation about how to manage investment hype. And the answer lies on the demand side.

For investors inside China at a time of challenging economics, few industries are as attractive as the clean energy industry. And business leaders have focused on the risks of hot money and breakneck expansion of clean energy manufacturing capacity for some time now, particularly in the solar industry.

This was probably the origin of “overcapacity”. But in China, this has been a familiar, almost perennial discussion of investment and industrial cycles. While the US argument equates exports to overcapacity, Chinese companies argue that it is demand that determines overcapacity, and they make investment and expansion decisions based on projections of both domestic and global demand.

Q&A: What you need to know about electric vehicles (EVs) and their batteries

That said, the size of China’s domestic market means it will remain the “base” for Chinese manufacturers. In the overseas market, the “overcapacity” claim underscores the complexity and uncertainties Chinese companies face.

For Chinese policymakers, one obvious response to the new market dynamics should be taking domestic demand to new levels. That means addressing lingering questions for China’s renewable energy future – namely, how to resolve the impact of coal. China’s power market was designed for a system dependent on coal, but it needs reform to allow wind and solar to take the central role. Injecting new political momentum to accelerate the reform will be key.

The EU has long been concerned about China’s market dominance, and the “overcapacity” debate is pushing it to decide its role in this trilateral trade and climate dynamic.

Even before this debate erupted, the EU had already begun, subtly, to diversify supply chains and build its own industrial strength, reducing dependence on Chinese products. Last week, the EU announced a maximum tariff of 38% on imported Chinese-made electric vehicles, concluding that Chinese EV makers are benefiting from “unfair subsidies”.

At this stage, it’s still unclear if this is the end of the EU’s low-key approach to date. Cultivating an EU-based clean industry hub without compromising the global response to climate change is a challenge, especially as the EU positions itself as a climate leader.

Entering the fray of US-China tension only makes this feat more complex, especially given uncertainties on the US end in an election year. How the EU approaches this climate and trade nexus will ultimately shape the trilateral dynamic among the world’s three largest carbon emitters in the coming years.

The Canadian city betting on recycling rare earths for the energy transition

For China, where relations with the EU and other countries are concerned, it’s worth taking a step back and looking at the hidden messages in the “overcapacity” debate. Other countries want more than just Chinese products.

Climate leadership is not a buyer-seller relationship, but one between partners who want solutions that create local jobs, develop opportunities, and enable native development of a sustainable future.

China should see its role in the global clean transition as more than a manufacturing hub. The transition requires tools, technology, finance and know-how, and China has much to offer. It is time for China to think more creatively about how to leverage its industrial advantages to provide the solutions with which the world is currently under-supplied.