Marcio Astrini is the executive secretary of Observatório do Clima, a network of 120 Brazilian civil society organizations.

In a big country in the Americas, an elderly leader defeats his far-right rival by a narrow margin. After facing a coup attempt, he starts off his government reversing several of his predecessor’s nefarious policies, rebuilding federal governance, and proposing ambitious measures to tackle the climate crisis.

Soon, however, it becomes clear that the new government can’t or won’t deliver on its progressive agenda: the president faces severe hurdles in a Congress tipped to the far right. The elderly leader’s popularity starts to plummet, even though the economy is doing fine, and job creation is spiking. His adversaries regroup and are threatening to take back power at the next election.

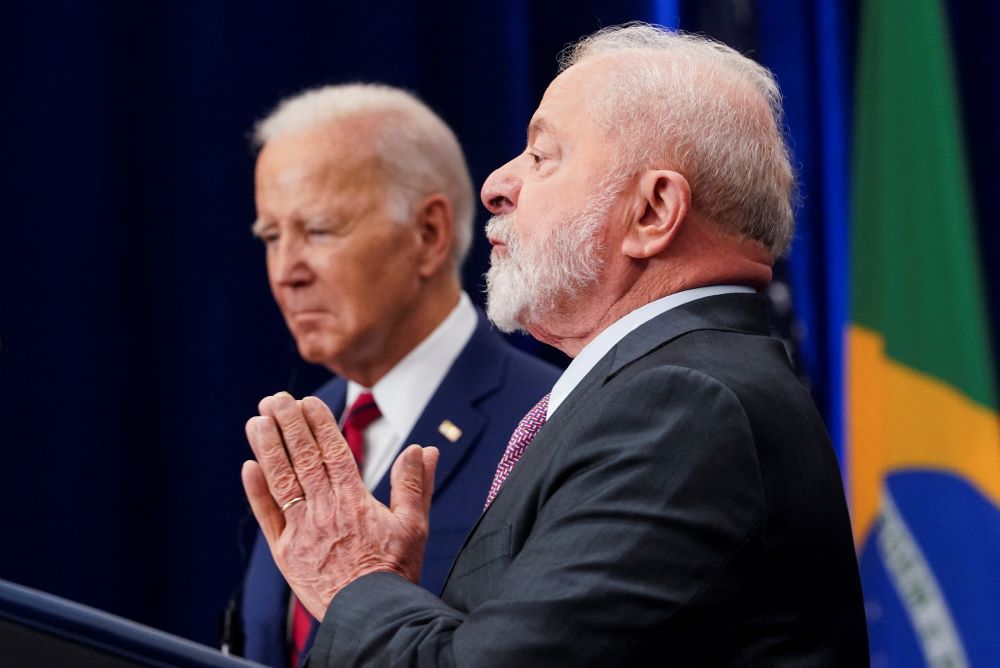

This could be the story of the United States – but it’s Brazil we’re talking about. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, 78, led in 2022 a coalition of democrats across the political spectrum to salvage his country from the grip of autocracy.

Slow progress in Baku risks derailing talks on new climate finance goal at COP29

His tightly won election was greeted with relief by the international community, but environmentalists had particular reason to celebrate. Lula’s far-right predecessor saw Amazon deforestation increase by 60% over his term and turned Brazil not only into a pariah but also a liability for the global fight against climate change.

More environmentally conscious now than in his two previous administrations, former union leader Lula vowed to prioritize the fight against the climate crisis. He gave native Brazilians a seat in the cabinet for the first time and promised to end deforestation by 2030, starting by re-enacting the Amazon Deforestation Control Plan that made Brazil a success story of climate mitigation in the past.

Lula also offered to host the 2025 UN climate conference in Brazil, resurrected environmental funds, and corrected his country’s embattled climate pledge. The efforts paid off: in 2023, Amazon deforestation dropped by 22% and a further reduction is expected for 2024.

Stakes high for COP30

Understandably, the world started to look up to Brazil in search of leadership in this critical decade for climate action. As Europe has weakened its position in the wake of farmers’ protests and the rise of the far-right in the EU parliamentary elections – and the US faces the threat of Trump 2.0 – the stakes are getting higher for COP30, the UN climate summit to be held in the rainforest city of Belém next year under Lula’s baton.

Alas, Mr. da Silva has little to show for it so far. The Brazilian president has faced a hostile Congress, dominated by the far-right and the rural caucus, and empowered by Jair Bolsonaro, whose government gave Congress increased control over the federal budget.

In the tough negotiations with such a parliament, the environmental agenda has been a bargaining chip. More anti-environment and anti-Indigenous bill projects have advanced since 2023 than during the whole Bolsonaro administration.

Right now, three dozen legislative proposals are under examination that could make it impossible to control deforestation and meet the country’s climate pledges. Lula’s negotiators in Congress have faced this barrage with embarrassing apathy.

In a situation similar to that of Joe Biden in the United States, Lula’s polling has dropped – for no obvious economic reason. Joblessness is at its lowest since before the 2015 recession; inflation is under control; real wages have increased, and with them the purchasing power of families; and GDP growth, though mediocre, is steady.

The perceived weakness of a government that has so far failed to make transformative changes (and whose greatest merit is precisely to make Brazil normal again) works as the proverbial blood in the water for the opposition: as a result, the government gets even weaker and more likely to forgo progressive agendas.

New oil and roads

To be sure, a fair share of environmentalists’ disappointment stems from Lula’s own actions. The president has been determined to make Brazil the world’s 4th biggest oil producer (today it ranks 9th) at the expense of the global climate, even though Brazil right now is ablaze and its major cities are covered in smoke from record-breaking wildfires.

Lula’s plan involves opening up new hydrocarbon frontiers both on land and offshore, including in the Amazon. His administration is also hell-bent on constructing a highly controversial road that cuts through the heart of the rainforest, which is feared to facilitate land-grabbing and illegal timber extraction and could increase emissions from deforestation by 8 billion tons by 2050.

Human rights must be “at the core” of mining for transition minerals, UN panel says

Da Silva’s Workers’ Party is riddled with old-school backers of national development who don’t believe in the green economy and isolate pro-climate officials such as Finance Minister Fernando Haddad and Environment Minister Marina Silva. Bizarrely, Lula also bets his international prestige on non-starters, like Ukraine, while leaving unattended the only geopolitical agenda where he and his country could really make a difference: climate change.

“Lead by example” is a motto of the Brazilian government whenever it tries to portray itself as a trusted champion of the Paris Agreement global warming limit of 1.5oC. Right now, the world would do better searching for leadership elsewhere. The good news is that Lula can still be persuaded to wear the mantle. COP30 is his golden opportunity – but it is a window that will not remain open for long.