Delegates from more than 175 countries are in Busan, South Korea, this week to hammer out an environmental deal described as the most significant since the Paris Agreement.

This is the final scheduled round of negotiations for a legally binding Global Plastics Treaty, promised by world leaders two years ago in a historic commitment to ending the crisis of plastic pollution across its lifecycle – including production, design and disposal.

But after four rounds of meetings, in which a small number of fossil fuel-rich countries dug in their heels to delay progress and water down ambition, it is still all to play for in Busan.

State of play on plastic production

On the eve of the negotiations, 1,500 activists marched in Busan and civil society groups delivered a petition of almost three million signatures, demanding a strong treaty that includes plastic production reduction measures.

They are particularly worried because a central point of contention among delegates is whether the treaty should regulate plastic production at all.

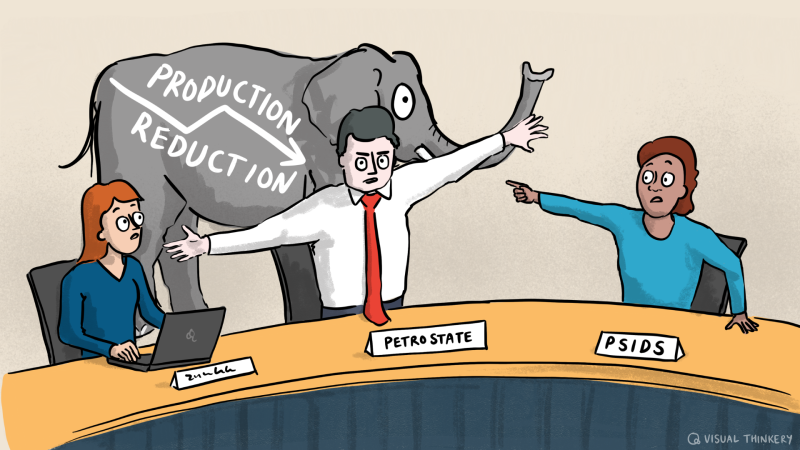

“It’s the elephant in the room,” said Swathi Seshadri, oil and gas lead at India’s Centre for Financial Accountability. “The petro-states and petrochemical-producing countries are pushing to keep the ambition low, but a majority of countries do want a strong treaty with upstream measures, including regulating polymer production and chemicals of concern.”

Cartoon courtesy of Visual Thinkery

While it is the important ‘downstream’ harms of plastic waste that predominate in the public imagination – marine life choked by packaging, microplastics in human placenta and so on – the production of plastic contributes directly to planetary warming and harms human and environmental health.

Environmental Investigation Agency campaigner Jacob Kean-Hammerson explained: “The pollution doesn’t start when plastic misses a bin on the street. As soon as we start to produce plastic, toxic chemicals leak into the environment, causing harm to frontline communities.”

Primary plastic polymers – the building blocks of any plastic product – are made from fossil fuels through energy-intensive refinement processes, and hazardous chemicals are often added to make the materials more flexible or resilient.

“Moment of truth” for plastic pollution as treaty talks get underway

The $712-billion plastic industry is set to double or triple by 2050, which would see plastic production account for up to 31% of the remaining global carbon budget for staying below 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming.

Campaigners want mandatory targets to cap and dramatically reduce virgin plastic production, eliminate single-use plastics, and ban toxic chemicals in all virgin and recycled plastics.

‘Get out of jail free’ card for fossil fuels

Griffins Ochieng, of the Centre for Environmental Justice and Development, told Climate Home: “The controls must be global, obligatory and measurable to be meaningful, otherwise countries in the Global South – that are not major producers of these polymers or chemicals – just have no way they can control what is happening in other places.”

However, some major fossil fuel-producing countries – like Saudi Arabia, Russia and Iran, as well as an ever-increasing number of industry lobbyists – are pushing to exclude plastic production from the treaty altogether.

Kean-Hammerson explained: “Plastics are seen as a ‘get out of jail free card’ for the fossil fuel industry, because they can increase demand for their products even as we take action to reduce demand in the energy sector.”

Campaigners highlight the connection between plastics and fossil fuels at a rally ahead of talks on a new global treaty to end plastic pollution in Busan, South Korea. (Photo by Seunghyeok Choi on assignment for Break Free From Plastic and Uproot Plastics Coalition)

According to Melissa Blue Sky, senior attorney at the Center for International Environmental Law, petro-states’ efforts to obstruct the negotiations extend from the content of the treaty to the procedural elements of the meetings.

Rather than looking to resolve particularly divisive issues through voting, some low-ambition countries have pushed for a consensus-based decision-making approach instead, which would effectively give every country veto power over the treaty text.

As a result, Blue Sky explained, nothing has been finalised in the “non-paper” – a draft treaty text prepared by the meeting’s Chair as a jumping-off point for negotiations – and it lacks any suggested language on plastic production.

“It is highly unusual to be in the final scheduled negotiating meeting and have no agreed text,” Blue Sky added. “This is not a normal situation,” she said, reflecting that “there are extremely far apart visions of what this treaty could be and do.”

Non-toxic reuse and refill

In addition to capping plastic production, environmentalists say a strong treaty should also include legally binding, time-bound targets to scale up non-toxic reuse and refill solutions, accelerating a transition away from single-use plastic.

This could include policies that incentivise a shift to reuse systems, such as single-use plastic bans, and rejecting “false solutions” – techno-fixes that perpetuate business as usual, like waste-to-energy (WTE), whereby plastics are burned to generate power, producing highly toxic ash.

The fact that polluting technologies like WTE have been rejected in the Global North but are widespread in the Global South is “the nature of colonialism today”, CFA’s Seshadri pointed out.

A strong treaty would also look to eliminate waste colonialism, a practice by which higher-income countries offload waste to lower-income countries, where its disposal harms human health and the environment.

Environmental justice

A just transition for workers and communities along the plastics supply chain also needs to be at the core of a strong treaty, green groups argue.

This must include formally recognising waste pickers, who often work in unsafe conditions, and supporting frontline communities suffering from the toxic impacts of plastic production and disposal.

Jo Banner, co-founder of the racial and environmental justice organisation The Descendants Project, lives in one such community: Wallace, a town in the U.S. State of Louisiana, which was established by her ancestors and their peers who had been emancipated from slavery on nearby sugar plantations.

Wallace lies along an 85-mile stretch of land nicknamed ‘Cancer Alley’, where communities live beside some 200 fossil fuel and petrochemical operations – the starting points of plastic production – and suffer some of the highest rates of cancer and other illnesses in the country.

“We’ve been sacrificed for this,” said Banner. “It’s us who have to live on the fenceline of this pollution, in the same way we lived on the fenceline of the plantation.”

“This is not just about disposable products. It’s about disposable people. And when we stop looking at people as being disposable, that’s when we will see real change,” she said.

How a local victory against petrochemicals can spur global action on plastics

Finance for implementation

If delegates do leave Busan with an ambitious, binding and measurable roadmap to reduce plastic pollution, countries will need money to implement it.

How will those funds be delivered – and who will pay?

Campaigners are calling for a ‘polluter pays’ mechanism, where plastic producers would pay a levy on each tonne produced.

However, Kean-Hammerson warned that innovative private finance mechanisms must not come at the cost of public funding.

“[The] Polluter pays [principle] is often thought about in terms of companies – they are the ones putting the polymer and the plastics on the market,” he said.

But donor countries in the Global North should also dig into their pockets, he said, not just to show solidarity on a global issue, but also in recognition of the fact that they export a lot of waste to the Global South and have high levels of production and consumption onshore too.

As the talks continue in Busan, civil society is unwavering in calling for an ambitious, legally binding treaty. The outcome will hinge on whether high ambition countries are prepared to follow through on their public commitment to address the global plastic crisis – and bring others along with them.

Sponsored by Break Free From Plastic. See our supporters page for what this means.

Daisy Clague is a freelance journalist based in London, UK.