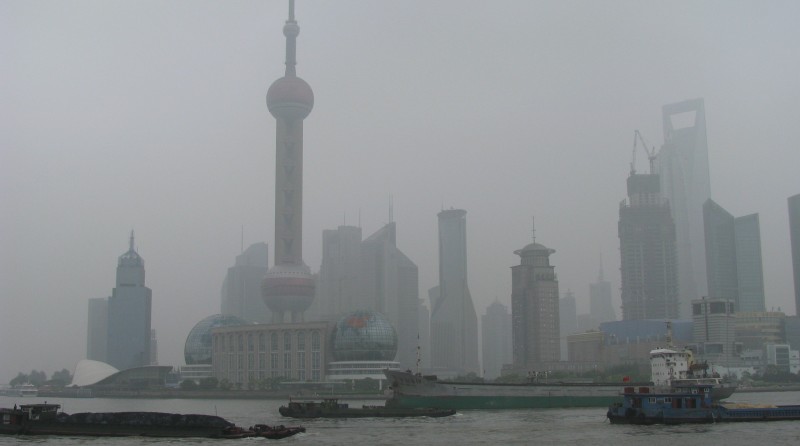

As you gaze out over the Huangpu River from its eastern bank, you see a skyline that epitomises Chinese prosperity and modernity – the Oriental Pearl Tower and the skyscrapers that surround it.

As would be expected from China’s largest and one of its most prosperous cities, Shanghai is at the vanguard of the country’s efforts to switch to lower-carbon technologies.

These, typically, range from green buildings and services that use less water, materials and energy, the promotion of recycling and reduction of wasteful consumption, and greater use of greener transport, such as electric vehicles, mass transit and cycle lanes.

As the video below shows, technologies such as green buildings could play a major role in helping the city reduce the rate of increase in CO2 emissions in households and offices. But the city’s rate of growth (since the start of the century its population has grown 50% to 24 million) will mean that greener urban planning, on its own, would only slow emissions growth, not reverse it.

That’s because behind Shanghai’s gleaming veneer of a service-based, high tech economy, lies a sprawling industrial base that accounts for 40% of the city’s economic output and around 60% of its CO2 emissions.

The city is also home to the world’s largest container port, ensuring that shipping (through the burning of bunker fuel) is major contributor to emissions of CO2 and of smog causing particulates.

If the city’s planners are to deliver a major slowdown in carbon emissions, mundane but economically essential industries such as power generation, chemicals and shipping and steel will need to install the best available technologies that cut energy use.

“People in China think cutting emissions means substituting [old] sources of energy with new ones. That’s a major misunderstanding,” said Zhu Dajiang, director of Shanghai Tongji University’s Institute of Governance for Sustainable Development.

Zhu holds that changing the energy mix is just one route to reducing emissions. Other approaches that centre on technology and management systems will be needed if China is going to achieve its goal of reaching peak carbon by 2030.

Shanghai Waigaoqiao 3rd Power Station has been using new technology to burn coal more efficiently. Its output of sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxide and particulate matter are now lower than those produced by natural gas power generation.

Plant manager Feng Weizhong estimates that if all China’s coal-fired power plants were as efficient 60 million tonnes of the 2 billion tonnes of coal burned per year could be saved, prompting atmospheric pollution to fall 80%.

Besides upgrading energy and infrastructure to make it cleaner and lower carbon, Shanghai will likely need to increase the share of services and higher tech industries in its economy, and shutdown or move out the dirtiest, most carbon intensive industries.

For example, the city is currently in talks with Sinopec about moving its refinery from the Shanghai district of Gaoqiao to somewhere outside the city limits.

But pushing a large share of heavy industry beyond the city’s boundaries is a difficult task, given that these sectors are major employers and have long benefited from strong political ties with regional officials.

Zhu corrected three common misunderstandings of where emissions come from.

This first refers to the assumption that China can peak its emissions by reducing transportation and building emissions. Indeed most emissions stem from industrial production, and to talk about an early carbon peak, while demand for transportation and buildings is still rising, is unrealistic, he adds.

Secondly, people assume reducing carbon intensity (per unit of living space) equates to reducing emissions. Not so, Zhu adds. Low carbon buildings just reduce the intensity of fossil fuels.

With more people buying bigger houses, carbon emissions are going up, he adds.

Thirdly, low carbon cities cannot be ‘built from scratch’ as some think. The overall speed and quality of economic growth are the determining factors, he adds.

Report: Singapore downplays renewable role in UN climate pledge

Wu Libo, an academic at Fudan University, thinks Shanghai can learn from Singapore. The two cities are similar in many ways. Both are international centres for trade, shipping and finance; both are home to ports with huge throughput figures; and both are guided by certain Chinese principles.

According to research by the China International Capital Corporation, in 2014 industry still accounted for 26.2% of Singapore’s GDP (compared to 35% in Shanghai). International Energy Agency statistics show Singapore ranked 123rd in terms of carbon emissions per GDP unit for 2015, while China was ranked 10th.

The aim of low-carbon development is to decouple emissions growth from economic growth. Low carbon cities tend to spring up in developed regions, therefore China can expect low carbon cities to take off only when it has higher GDP per capita.

“Shanghai might need to see per-capita GDP reach US$30,000 or US$40,000 before it can say that has happened,” said Wu Libo, adding that the city’s per-capita GDP currently is US$20,000 – still much lower than in Singapore where per-capita GDP stands at US$55,000.

Wu Zhiqiang, deputy president at Tongji University, leads a team researching emissions reductions within building clusters, a much more efficient approach than reducing emissions on a building-by-building basis.

“Green building clusters are a better choice for big cities such as Shanghai and Beijing. It’s hard for a single building to meet its own peak electricity demand, but coordinating across a community or building cluster allows power to be better allocated.”

Wu sees cities as living organisms.“And a real organism cannot live apart from its environment. It needs a local ecology, a regional labour supply, and for the region to better protect its traditions and resources.”

This article was produced by China Dialogue