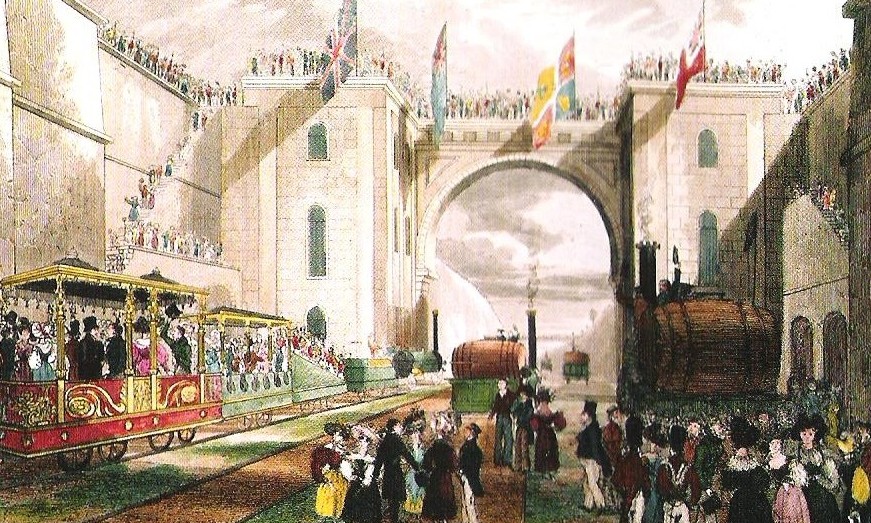

On December 4, 1830, the Planet chugged out of Liverpool on its maiden trip to the great manufacturing centre of Manchester.

Shovelled full of coal, the steam locomotive was hauling freight along the world’s first intercity rail route – a major advance in the industrialisation of the globe.

It was around this moment, scientists have discovered, that our own planet began to go off the rails.

Using 2,000 years of paleoclimate data – the earth’s historical temperature measured from natural sources such as the growth bands of corals and trees, ice cores and the amount of pollen trapped in sediment layers – a global team of researchers lead by Australian National University associate professor Nerilie Abram, have pinpointed the moment when the earth’s temperature began to rise because of human greenhouse gas emissions to between 1830 and 1850.

Abram said the findings, published on Wednesday in the journal Nature, were “extraordinary” and had implications for our understanding of the sensitivity of the globe to even tiny increases of carbon in the atmosphere.

A scientist extracts coral cores at Rowley Shoals, west of Broome in Western Australia.

Source: Eric Matson, Australian Institute of Marine Science

Study co-author, Dr Helen McGregor, from the University of Wollongong said: “The early onset of warming detected in this study indicates the earth’s climate did respond in a rapid and measurable way to even the small increase in carbon emissions during the start of the industrial age.”

Abrams said the increase in atmospheric carbon between the onset of warming and the end of the 1800s was “small”, around 15 parts per million. But even this raised the temperature by a few tenths of a degree. The increase since 1900 has been more than 100 parts per million.

Paleoclimate temperature records were most famously analysed in the 1990s by US scientist Michael Mann to produce the “hockey stick” graph, which shocked the world with its dramatic depiction of the rapid recent rise in temperature after a millennia of relative stability.

But these natural almanacs have never so accurately calculated the beginning of human-induced warming.

In a paleoclimatological first, Abram’s study incorporated not only land based sources like tree rings, but measured marine temperatures as well. The scientists found the land of the northern hemisphere and seas of the tropics began warming at roughly the same speed around 1830.

“Seeing that parts of the oceans are a very responsive part of the climate system is a new and very interesting bit of information,” said Abram. Particularly because those oceans contain some of the most climate sensitive ecosystems, coral reefs. The southern hemisphere was around 50 years behind. This was likely the result of cooling currents in the huge southern oceans.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z5VC98yZCu0

This regional variability also allowed Abram’s team to chart the different stages of “emergence” around the globe. That is the point at which the average temperature has increased so much that it exceeds even extreme natural fluctuations.

“In the tropical oceans and the Arctic in particular, 180 years of warming has already caused the average climate to emerge above the range of variability that was normal in the centuries prior to the Industrial Revolution,” said Abram. The Antarctic, however, remains stubbornly un-warmed to this day.

Because of the huge technological leaps and enormous new wealth that drove projects like the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, early industrial emissions were dominated by the United Kingdom.

According to the World Resource Institute, by 1850 the furnaces of the British industrial revolution had belched 122.6 million tons of climate-warming carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

This cumulative total was twice as much as the rest of the world combined had emitted to that point – most of it coming from Britain’s great rivals, France, the US and Germany. Today, Britain emits around 500 million tonnes every single year.

The findings shift our understanding of exactly what is normal, because instrumental records of the global temperature only reliably go back as far as 1880.

Using that baseline, Nasa has determined that the first six months of 2016 were 1.3C warmer than normal. But Abram says the world had already warmed a few tenths of a degree by 1880, pushing the world beyond the 1.5C limit already.

“That’s important for conversations that we are having at the moment about trying to limit warming to 1.5C. We are getting scarily close to that already, but that’s when we are talking about the baseline being in the 1880s-1900. So we don’t yet have the full picture,” she said.