The EU carbon market is supposed to make polluters pay. But generous handouts to industries deemed at risk of losing business abroad are undermining the system, a watchdog has warned.

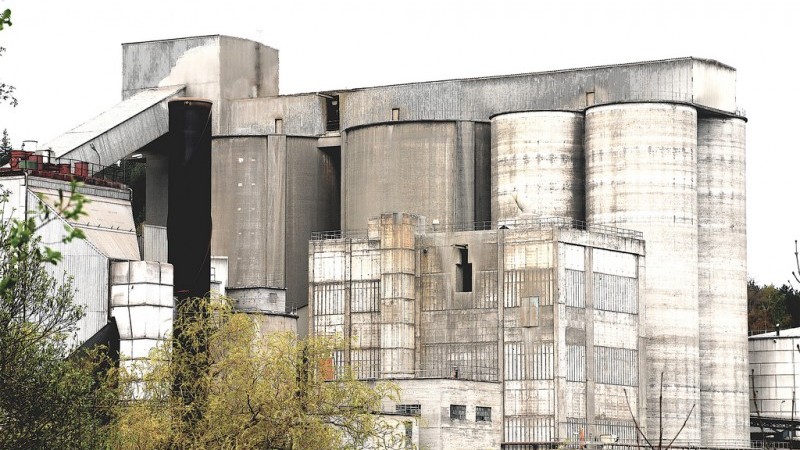

Cement producers reaped a €5 billion windfall from the emissions trading system (ETS) between 2008 and 2015, their annual reports reveal.

Companies like Lafarge, Heidelberg and Cemex profited from selling carbon allowances they received for free, substituting cheaper international offsets and passing through costs to customers.

Carbon Market Watch, which used analysis by consultancy CE Delft, is urging EU lawmakers to end the bonanza. The environmental committee meets to discuss carbon market reform on 8 December.

“The EU ETS has not only failed to decarbonise the sector, but it actually has had a reverse effect. We have seen an increase in emissions, because of the way the system is tailored,” said campaigner Agnes Brandt.

“Getting rid of surplus allowances in the system is paramount.”

Weekly briefing: Sign up for your essential climate politics update

The ETS is a cornerstone of Brussels climate policy, intended to drive emissions cuts across the economy in a cost-effective way.

Yet industries have successfully lobbied for free allowances, threatening to take thousands of jobs to less taxing jurisdictions overseas if they don’t get them.

A typical statement from cement giant Lafarge reads: “Unequal carbon pricing place[s] the EU manufacturing sector in general – and the cement sector in particular – at risk of carbon leakage.”

Those carve-outs, coupled with a downturn in demand since the 2008 financial crisis, have depressed the carbon price to around €5 a tonne of CO2.

Meanwhile, the subsidy relieves pressure on the sector to shift to lower carbon technologies and processes.

Donal O’Riain, managing director of Ecocem, which specialises in environmentally friendly cement, said the rules actively disadvantage green innovators.

If his company, a relatively new entrant, succeeds in taking market share from an incumbent, the latter benefits from selling un-needed carbon allowances.

“That is really a horrific competitive situation,” he said. “You can’t invent a system more counterproductive than that one.”

Options for decarbonising cement – responsible for 5% of global emissions – include substituting the carbon-intensive ingredient “clinker” with limestone or waste from other industrial processes; capturing and storing the flue gases; and using the end product more efficiently.

At the moment, cement is so cheap, O’Riain said, “it is not used in the most careful or optimised way”.

Jessica Johnson, spokesperson for lobby group Cembureau, told Climate Home the €5bn figure was “grossly exaggerated”.

Specifically, she disputed the claim that €2.1bn of carbon costs had been passed through to customers. Between 2007 and 2014, she said, EU cement production had declined 40% on weak demand. In those market conditions, producers were not in a position to charge higher prices.

The watchdog’s calculation did not give the industry credit for spare allowances generated by carbon efficiency measures, she added – while acknowledging that the handouts had been overly generous.

“The cement industry has always been in favour of a allocation system which is much more closely aligned to actual production,” said Johnson by email. “Indeed, we fully agree that installations should not receive more free allowances than they need and should be allocated at the level of best perfomers.”