Over the past few years there has been exponential growth in clean energy investment – while fossil fuel assets are increasingly considered to be risky.

Yet, on February 6, the European Investment Bank, the EU’s long-term lending institution, voted to provide a €1.5 billion loan to the controversial Trans Adriatic Pipeline (Tap).

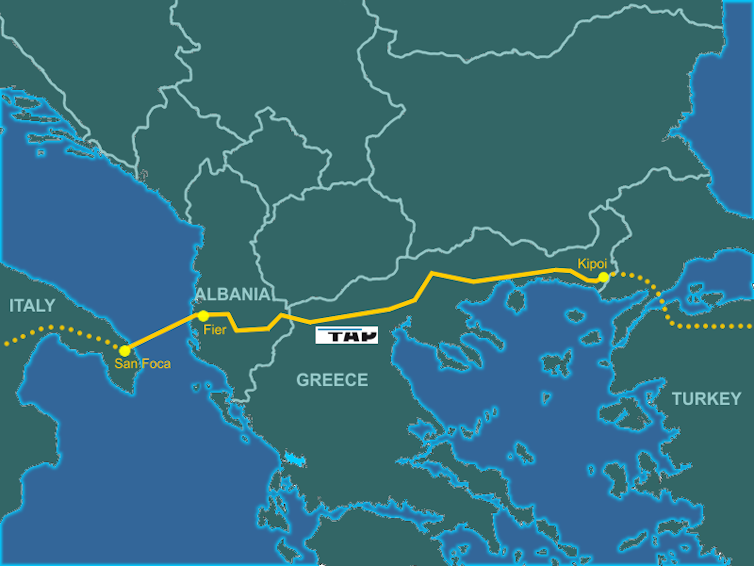

The Tap is the Western part of a larger Southern Gas Corridor proposal that would ultimately connect a large gas field in the Caspian Sea to Italy, crossing through Azerbaijan, Turkey, Greece and Albania. And while gas might be cleaner than coal, it’s still a fossil fuel.

So how does the EU’s support for this major project fit in with its supposed goal of addressing climate change?

The proposed Trans Adriatic Pipeline will run nearly 900km from Greece to Italy (Pic: Genti77 / wiki, CC BY-SA)

A key problem is the message this sends to the private sector, where renewable energy is increasingly seen as a good investment. Technologies once perceived as too risky and too expensive are now delivering worthwhile returns thanks to reduced costs and breakthroughs in energy storage. The price of electricity generated by solar, wind or hydro is now comparable with the national grid.

Over the past decade, investor meetings have shifted from discussing whether the transition to a low carbon economy will start before 2050, to whether it will be completed in the same period.

#Pipeline parts being laid out end to end (stringing) – this is now complete for more than 633km of #TAP route. #engineering #energy #energysecurity pic.twitter.com/O6jpwVJ0K3

— TAP (@tap_pipeline) January 5, 2018

But there is still not enough money being spent on renewables. While clean energy investment in 2017 topped US$300 billion for the fourth year in a row, this is far short of what is needed to unlock the technology revolution necessary to tackle climate change. There is clearly a gap between what is required and what is being delivered.

The private sector will continue to invest significant capital into energy projects over the next few decades, so one issue facing policy makers is how to influence investors away from fossil fuels and towards renewable projects. To really scale up investment into renewable infrastructure, long-term and stable policy is required – which investors see as clearly lacking.

By funding the Trans Adriatic Pipeline, the EU’s investment bank is hardly signalling to the private sector that governments are committed to a green energy transition.

If Europe really was to follow through and successfully switch to green energy – and such a transition is partially underway – then the pipeline project may even represent a risk to public finances.

Studies on climate change point to the need for a greater sense of urgency and ambition and, to stay within its “carbon budget” under current agreed emissions targets, the EU needs to be fossil fuel free by 2030.

So any large oil and gas infrastructure projects with investment returns beyond 2030 are saddled with risk. In just a decade or two, super-cheap solar and wind power could mean that gas pipelines such as TAP would no longer make financial sense and would become worthless “stranded assets”. Yet TAP backers are touting economic benefits for countries such as Albania extending to 2068 – well beyond the date when Europe must entirely ditch fossil fuels.

The EU’s official stance is to hail natural gas as a cleaner “bridge fuel” between coal and renewables. But high leakage rates and the potent warming impact of methane (the primary constituent of natural gas) means that the Southern Gas Corridor’s climate footprint may be as large, or larger, than equivalent coal. Abundant natural gas is also highly likely to delay the deployment of renewable technologies.

We’re taking on Big Oil because it’s the right thing to do to protect the future of our city and our planet. pic.twitter.com/kezomaxKiL

— Bill de Blasio (@NYCMayor) January 13, 2018

For the first decade of this century Europe prided itself on leading the political debate on tackling climate change. Now, it appears to be losing its boldness. To drive through a new technology revolution, the public sector needs to lead from the front and take bold decisions about its energy strategy.

![]() A gas pipeline is not a technology of the future. If California can release YouTube videos describing the importance of considering stranded assets during this energy transition, and New York City can announce plans to divest from fossil fuels, then maybe it is time for the EU to turn off the TAP.

A gas pipeline is not a technology of the future. If California can release YouTube videos describing the importance of considering stranded assets during this energy transition, and New York City can announce plans to divest from fossil fuels, then maybe it is time for the EU to turn off the TAP.

Aled Jones is a professor and director of the Global Sustainability Institute at Anglia Ruskin University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.