As she considers setting a date for the UK emissions to hit net-zero, the energy and clean growth minister said fracking for new gas resources remained “pragmatic policy”.

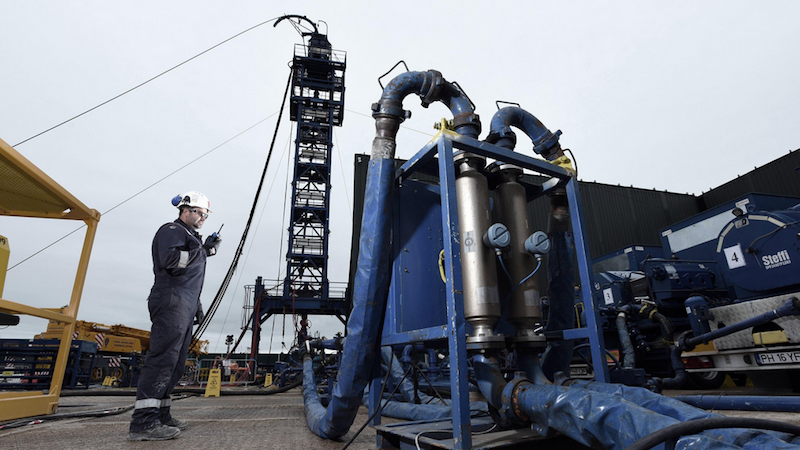

Operations restarted at a shale gas site in north-west England on Monday after a seven-year hiatus, despite local opposition and an activist blockade.

Meanwhile Claire Perry was promoting “Green GB” week at a Chatham House conference in London. Also on Monday, Perry wrote to the independent Committee on Climate Change (CCC) to formally request advice on when the country should reach net zero emissions in light of a heavyweight UN science report published last week.

“I strongly believe that gas is absolutely part of our future,” she said in response to a question from Climate Home News about the compatibility of gas and reaching net-zero pollution.

Natural gas supplies around 40% of UK electricity and 80% of home heating. It is part of the energy mix in “every major pathway” to reduce emissions modelled by the CCC, Perry said. “I have not seen a single bit of modelling that shows 100% renewables is viable.”

There have been attempts to map a 100% renewable future, but their practicality is the subject of debate.

What happens in the next few months will impact the future of the Paris Agreement and the global climate

CHN will be there keeping you informed from the inside.

If you value our coverage, please consider helping us. Become a CHN patron for as little as $5 per month.

We have set up a Patreon account. It’s a simple, safe and easy way for you to become part of a community that will secure and guide our future.

Thank you!

Defending “pragmatic policy”, Perry credited gas with helping Britain to shift away from coal and clean its economy much quicker than Germany. PricewaterhouseCoopers analysis shows the UK reduced its emissions for each unit of GDP in 2017 by 4.7%, compared to Germany’s 2.8% reduction.

The UK is increasingly a net importer of gas, as North Sea supplies dwindle. Perry said that domestically-produced gas would be better regulated than other sources.

The CCC has cautiously backed fracking, so long as carbon pollution from gas remains within the UK’s legislated carbon budgets.

“What I find very difficult is we are determined people must accept the science of climate change but when our scientists tell us fracking is safe and part of a low carbon future we reject that,” said Perry.

UN scientists last week reported that if warming was to be held to a safer limit of 1.5C, global emissions would have to reach net zero around 2050. For gas to continue to be a source of power after that, it will need to be accompanied by carbon capture – an unproven technology for which the UK scrapped a major research programme.

In a statement, CCC chair John Gummer said: “The difference in the impacts that we can expect to see with 1.5 and 2 degrees of warming is considerable.” An appropriate response would mean reviewing whether the UK’s current target of 80% emissions cuts by 2050 was “fit for purpose”.

Mary Creagh, a lawmaker with the opposition Labour party and chair of the parliamentary environmental audit committee, told Climate Home News the government energy stance was “problematic”. Labour has promised to ban fracking in the UK.

The current Conservative administration cut support for onshore wind power at the same time as pursuing fracking. “Those priorities are the wrong way round,” she said, on the sidelines of the Chatham House conference.

Creagh also criticised a recent freeze on fuel duty for motorists, describing it as a “£2 million subsidy to fossil fuels” and cuts to support for electric vehicles.

What is net-zero carbon?

Without naming it, the Paris Agreement defined carbon neutrality when it called on countries to strike a “balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases” by the second half of the century.

Carbon neutrality, or ‘net-zero’, allows for continued emissions as long as every tonne of greenhouse gas released is offset or sequestered by an equivalent amount. There are many ways of doing this. Key existing methods include the planting of trees and management of land. But some experts also advocate technofixes, such as the use of biofuel that draws carbon dioxide from the air alongside carbon capture and storage, catching the pollution and locking it underground.