Environmental groups are suing the Canadian government over its approval of an oil extraction project two days after the world’s leading climate science authority warned fossil fuel infrastructure needed to be downsized.

The Bay du Nord project off the coast of Newfoundland, developed by Norwegian company Equinor, would extract 300 million barrels of oil over 30 years with production expected to start from 2028.

UN head António Guterres described investments in new fossil fuel infrastructure as “moral and economic madness” and slammed countries doing so as “dangerous radicals”.

But veteran campaigner turned environment minister Steven Guilbeault approved the $12bn project last month after an environmental assessment concluded it is “not likely to cause significant adverse environmental effects” if mitigation measures were imposed.

The move didn’t impress his former colleagues. Environmental law charity Ecojustice filed a petition at Canada’s Federal Court to overturn the decision on behalf of the Sierra Club Canada Foundation and Équiterre, which Guilbeault co-founded and led until November 2018.

Philippines inquiry finds polluters liable for rights violations, urging litigation

Campaigners will argue the project is incompatible with Canada’s climate obligations and that the environmental impact assessment was “deeply flawed” and failed to take into account emissions from burning the oil.

“Equinor’s Bay du Nord flies in the face of climate science and would be a clear violation of our attempts to meet climate targets,” said Gretchen Fitzgerald, national programme director at the Sierra Club Canada Foundation ahead of Equinor’s annual general assembly (AGM) on Wednesday.

Fitzgerald, who grew up in Newfoundland, called on investors to push the company to cancel the project and invest in renewable energy and particularly wind projects. During the meeting, several interventions called on the company to shift its business model away from oil.

Addressing investors, Jon Erik Reinhardsen, chair of Equinor’s board of directors, insisted that the company’s strategy and net zero plans were in line with global climate goals but that the company also sees “a significant exploration potential especially around our existing infrastructure”.

Reinhardsen argued that the company was prioritising projects “with the highest value and lowest emissions” internationally.

Climate scientists and the International Energy Agency have said that investment in new oil and gas projects is incompatible with meeting global climate goals.

Upon approving the project, the government imposed 137 legally binding conditions for Equinor to develop the project. This includes measures to reduce emissions from the project so that it reaches net zero emissions from its operations by 2050.

The government said the project will be five times less emission intensive than the average Canadian oil and gas project and described it as “an example of how Canada can chart a path forward on producing energy at the lowest possible emissions intensity while looking to a net-zero future”.

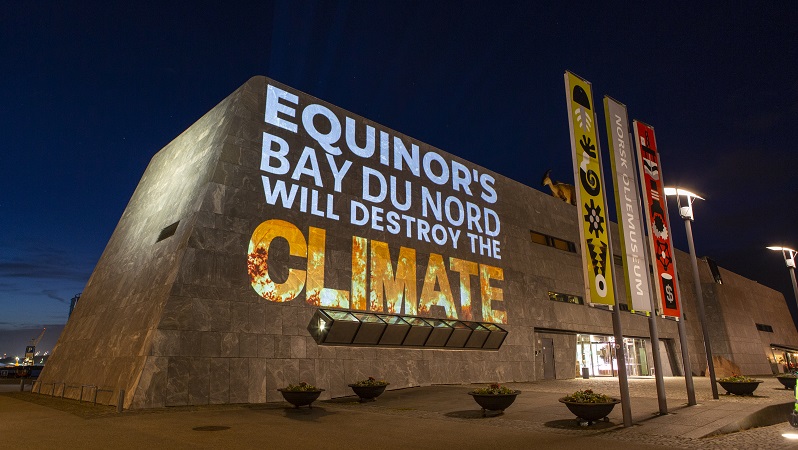

But it faces mounting opposition from campaigners and youth activists. On the eve of Equinor’s AGM, campaigners projected testimonies of Canadians who oppose the project on buildings across the town of Stavanger, where the meeting was held.

Emissions from oil and gas extraction continue to rise in Canada and account for more than a quarter of the country’s total emissions – the highest-polluting sector.

From extraction to oil use, the project would emit the equivalent of adding 7 to 10 million fossil fuel cars to the road, according to NGO analysis. Even if the project were to use carbon capture and storage technology, they estimate the oil produced would still emit 10 to 52 times the amount captured.

A review of the impact assessment by a governmental science body concluded that the document was not a reliable source for decision-making because risks were “significantly underestimated” and some information was omitted or “cut and pasted” from other assessments.

Governments risk $340bn in legal claims for limiting oil and gas projects, study finds

Equinor, previously known as Statoil, has pitched itself as an energy company with a leading role to play in the energy transition but it continues to expand its oil and gas business.

Last month, it announced the discovery of 25-50 million barrels of recoverable oil near its current operations in the North Sea.

Its oil expansion has led to more confrontation with campaigners in Argentina, where Greenpeace has filed a lawsuit against the approval of the company’s plans to carry out exploratory seismic drilling in the Argentine Sea to determine whether there is oil and gas under the seabed.

“People in Argentina and Canada are shocked at how Equinor is pushing to open up new and vulnerable areas for oil extraction in their countries, and there is no sign that Norway will put the brakes on for their own oil and gas exploration,” said Ragnhild Waagaard, of WWF Norway.

“This must stop as there is no room for new oil and gas fields if we are to achieve the goals in the Paris Climate Agreement.”