African leaders have stopped short of calling for a phase-out of fossil fuels in a joint declaration that forms the basis of their negotiating position at the Cop28 climate summit in November.

The document signed by heads of state at the inaugural Africa Climate Summit underscores a missing consensus between countries championing renewable energy and those arguing fossil fuels – and gas especially – are needed for economic development.

The leaders united behind an appeal for financial reforms, including new global taxes and debt relief, to fund climate action on the continent.

Old pledge

The eight-page declaration mentions fossil fuels only in calling on the global community to “uphold commitments to a fair and accelerated process of phasing down coal and abolishment of all fossil fuel subsidies”.

That is a reference to the key pledge the governments agreed upon at Cop26 in 2021. Since then, however, campaigners and a number of nations have been pushing for the extension of that commitment to all fossil fuels.

An attempt to achieve that at last year’s Cop27 was backed by a broad coalition including India, the EU, US, UK, Chile and Colombia. But it ultimately flopped following opposition from oil-producing countries led by Saudi Arabia and Russia. Africa’s negotiating group did not take a public stance on the issue in Sharm el-Sheik.

The battle is likely to resurface at this year’s climate summit. Its hosts, the United Arab Emirates, have put the phase-down of fossil fuels on the agenda, with president-designate Sultan al-Jaber saying this is “essential” and “inevitable”.

Decarbonisation vs development

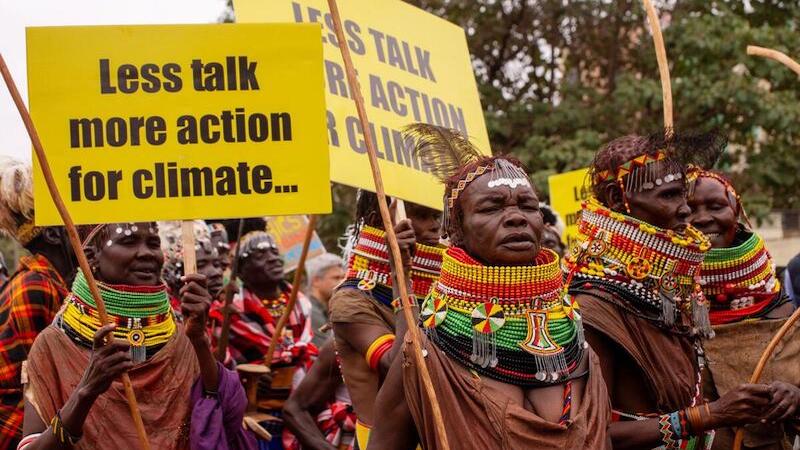

At the three-day gathering in Nairobi, talk of fossil fuels was notable for its absence. Kenya’s president William Ruto led calls for fast-tracking green growth, saying the continent has “untapped renewable energy potential”. Ninety percent of Kenya’s electricity is delivered by renewables.

Other African nations have significant fossil fuel interests. Nigeria and Angola are major oil producers, while Senegal and Mozambique have been expanding their gas industries. South Africa is implementing a clean energy transition plan, but it still relies on coal for the vast majority of its power generation.

Fossil fuels are at the heart of the tension between decarbonisation and development. Around 592 million people lack access to electricity across Africa and the continent’s historical contribution to the climate crisis is a fraction of that from rich nations.

To grow their economies African countries must be able to use gas power, alongside renewable energy, African Development Bank (AfDB) president Akinwumi Adesina said during a fiery speech on Monday.

“People think it is controversial, but for me, it is not,” he said. “We are going to use all the renewable energy sources we have, but they are variable resources. Africa needs stable grids to industrialise. Gas is a very critical part of the energy mix.”

The AfDB has supported the construction of gas infrastructure across Africa, including a controversial LNG terminal in Ghana.

Climate finance demands

With a clear focus on finance, the Nairobi Declaration is heavy on demands that polluters major polluters channel more money toward poorer countries bearing the brunt of the climate crisis.

African leaders urged the introduction of global taxes on financial transactions and carbon emissions to fund investment in climate actions. The declaration also advocates for reforms to the multilateral financial system, an increase in financing with favourable terms and debt pauses following climate disasters.

The heads of state have also repeated pleas that rich countries “honor the commitment” to provide $100 billion in annual climate finance – a target that has been missed repeatedly.

Lily Odarno, a director at the Clean Air Task Force, told Climate Home the summit had a “narrow focus on finance” and did not sufficiently explore broader trends facing Africans. “There are lots of targets without an actionable framework to achieving them, so we expect to see a lot more detail in Dubai.”