Development funding for biodiversity grew significantly in 2022, but the money came mostly in the form of loans rather than grants, according to new figures from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

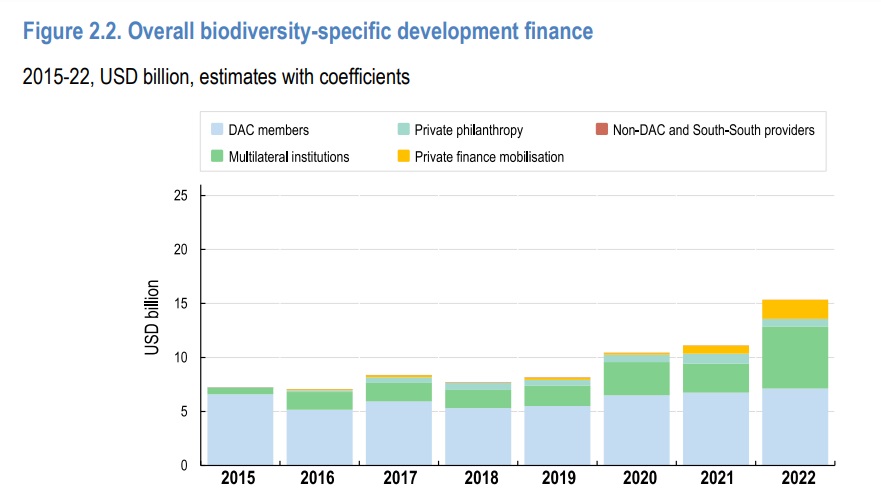

The OECD report, which analysed the period from 2015 to 2022, shows that funding for efforts to protect and restore nature grew from $11.1 billion in 2021 to $15.4 billion in 2022.

The increase came largely from multilateral institutions – mainly development banks – which increased their funding from $2.7 billion in 2021 to $5.7 billion in 2022, mostly by offering concessional loans, which are cheaper than borrowing on commercial terms.

The issue of whether loan finance should be provided to already debt-strapped developing countries for action on climate and nature is hotly debated, with poorer countries and climate justice activists calling for more money to be disbursed as grants.

Multilateral funding for biodiversity (in green) saw the biggest increase between 2021 and 2022, mostly in the form of loans. (Photo: OECD)

Boosting funds for biodiversity protection will be a key issue at the COP16 UN conference in Colombia late next month, as countries face the challenge of meeting a goal to mobilise $20 billion by 2025 – a sum agreed two years ago at COP15 in Montreal. This, in turn, will influence the creation of new national biodiversity plans, experts say, which could also help curb rising carbon emissions.

To channel some of this money, governments agreed at COP15 to set up a new international biodiversity fund established under the Global Environmental Facility (GEF). It has struggled to get off the ground, receiving a scant $200 million so far.

“It is critical that historic and new donors arrive at COP16 with substantial new funding announcements for developing countries – primarily in public grants, not loans,” said Brian O’Donnell, director of the advocacy group Campaign for Nature.

Causes for concern

While it is “certainly good news” that biodiversity funding has increased in the years leading up to 2022, there are some concerning trends, O’Donnell told Climate Home News.

For example, he pointed to a disparity between funding for projects marked as “biodiversity-specific”, which has the principal goal of reversing biodiversity loss, and funding marked as “biodiversity-related”, which is mainly aimed at tackling a different problem but yields some benefits for biodiversity.

The OECD report shows that, while overall biodiversity funding increased, the amount with the principal goal of tackling biodiversity loss decreased, falling from $4.6 billion in 2015 to $3.8 billion in 2022.

“We can’t safeguard nature and the planet just by making it a tangential approach to other funding endeavours,” said O’Donnell. “The majority of the funding has to be with the true desire to safeguard nature.”

Oscar Soria, a veteran biodiversity campaigner and CEO of The Common Initiative, an environmental think-tank, agreed that the lack of funding dedicated directly to biodiversity could limit efforts to protect conservation areas and restore nature.

The prevalence of loans over grants also poses a challenge for developing countries, the two experts said. “With development budgets shrinking in key donor countries, the future of real biodiversity protection hangs in the balance,” Soria added.

The OECD report shows that most direct public funding came in the form of grants, but this type of finance has grown very slowly in the last decade, creeping up from $6.6 billion in 2015 to $7.1 billion in 2022.

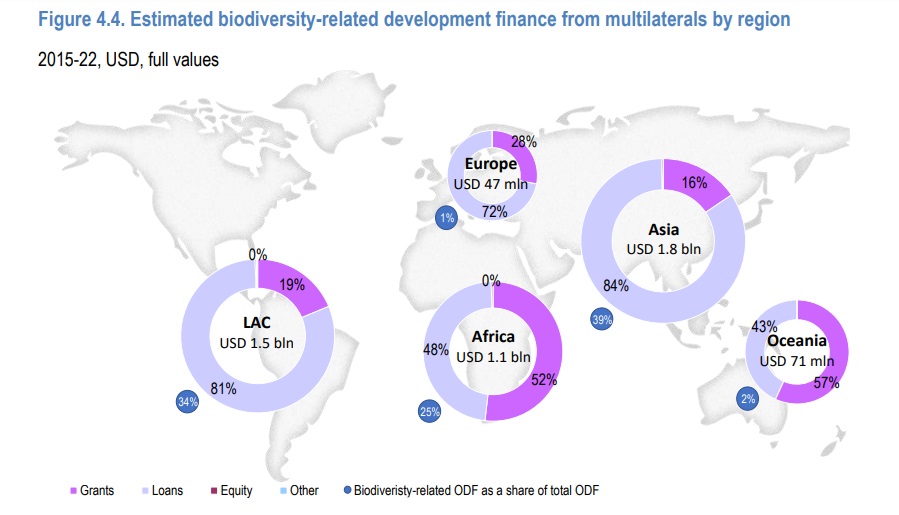

Asia and Latin America were the top recipient regions for biodiversity finance from multilateral institutions, but most of it came in the form of loans. (Photo: OECD).

Funding gap

Based on the trends shown in the OECD report, Soria noted that governments “should be able to deliver” the $20-billion goal for international public finance by 2025.

O’Donnell agreed that the goal should be within reach, but said that implementing the Global Biodiversity Framework agreed in Montreal – which includes a target to protect at least 30% of the planet’s land and sea by 2030 – will require major additional financing.

“Countries should look at this and say ‘we need to aim higher’,” he added.

The gap on a longer-term finance goal that includes all sources – for $200 billion by 2030 – is much wider, as the report shows that currently governments have mobilised only around $25.8 billion in total for biodiversity, including from the private sector.

In the case of multilateral institutions, the funds committed for biodiversity between 2015 and 2022 represent just 3% of all development finance disbursed in those years. Top recipients included China ($750m), Colombia ($338m) and Mexico ($207m).

Donor countries, meanwhile, remain small in number, with only five governments responsible for nearly three-quarters of the biodiversity funding provided between 2015 and 2022.

“This cannot be just an accounting exercise,” O’Donnell told Climate Home. “Ultimately, this needs to be an impact exercise – one that is focused on halting and reversing biodiversity loss.”

(Reporting by Sebastián Rodriguez; editing by Megan Rowling)