The European Central Bank (ECB) is standing in the way of a plan by African and Latin American development banks to mobilise large amounts of finance to tackle climate change.

The Frankfurt-based ECB sets rules for the 20 European countries that use the Euro currency, and has told their national central banks not to re-channel a type of financial asset known as special drawing rights (SDRs) to multilateral development banks (MDBs).

This has scuppered an attempt by the African Development Bank (AfDB) and Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) to persuade rich nations to give their SDRs to them – where they argue the money can go further – rather than back to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

SDRs are issued by the IMF as a way of supplementing its member countries’ foreign exchange reserves, allowing them to reduce their reliance on more expensive domestic or external debt for building reserves. They can be held and used by member countries, the IMF and designated official entities called “prescribed holders”, which include some central banks and regional development banks. Governments will discuss how they are used at the IMF’s annual meeting in Washington DC this week.

Pepukaye Bardouille, special adviser on climate resilience to the Barbados prime minister, told Climate Home in a press briefing last week that Eurozone countries “have struggled” to give their SDRs to the AfDB and IDB “because of restrictions of the [ECB] that hinder their ability to re-channel”.

Laurence Tubiana, CEO of the European Climate Foundation, said during the same briefing that the ECB’s rules are a “problem”, noting that central banks “are very averse to risk”. “All this money sitting in central banks doesn’t really work for development and for all the big issues we have to face,” she said. This is a moment where we “have to open all the boxes” of finance, she added.

Laurence Tubiana as a UN high level climate champion in 2016 (Pic: UNFCCC/Flickr)

Explaining the ECB’s reluctance in a recent online article for the Center for Global Development, leading economists Vera Songwe and Mark Plant wrote that central banks use their reserves to ensure the smooth flow of trade and to support their currencies.

“They loathe using them to pay for current spending or investments in their own countries, much less others,” they explained. “Lending to MDBs is seen as chipping away at high-income countries’ financial safety margins to help bail out developing countries that are a world away.”

Pandemic bail-out cash

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit the global economy, cash-strapped developing countries and small island states that cannot borrow easily because of low credit ratings asked the IMF for financial support.

The IMF responded by issuing $650 billion worth of SDRs. By default, these are allocated to countries according to the size of their economy which meant that the bigger, richer nations got the most, despite needing the least.

At the time, IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva urged rich nations to re-allocate their SDRs to smaller, poorer nations. The IMF set up two funds called the Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST) and the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT) – and rich nations re-allocated some of their SDRs to those.

In March 2023, the RST approved its first batch of loans, including $764 million for Jamaica to invest in renewables and energy efficiency.

Parametric triggers: How small islands can escape climate-poverty trap

But critics pointed out that the RST adds to national debt burdens and only countries with an existing IMF programme can access it, excluding many in need.

The AfDB and the IDB argued that channeling the money to them – instead of to the RST – would allow them to “leverage SDRs by up to four times their value in the form of loans to finance social and climate projects”. As the RST is not a bank, its ability to leverage is limited.

AfDB President Akinwumi Adesina said in May that the proposal was “an innovative approach through which development financing can be mobilized with a multiplier effect and at no cost to taxpayers. These are the types of solutions we need to help us tackle Africa’s growing development challenges.”

ECB’s cold water

But the proposal has received little interest. According to Songwe and Plant, no countries have taken the AfDB and IDB up on their proposal.

While the IMF gave it the green light in May, the ECB president Christine Lagarde said in 2022 that it “would not be compatible with the EU’s legal framework” for Eurozone nations to take part.

Since then, the ECB has continued to encourage Eurozone countries to channel their SDRs into the IMF’s two funds, but considers redirecting them outside of the IMF to be incompatible with the EU constitution’s ban on monetary financing.

The European Council has made a formal exception for rechannelling SDRs to the IMF because it considers them still to be reserve assets.

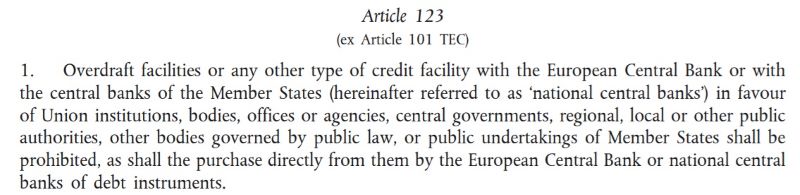

The ECB believes the proposal is incompatible with Article 123(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

While France and Italy have supported re-allocating SDRs to MDBs, the German central bank has opposed re-allocating SDRs, even to the IMF.

Tubiana said reform of the ECB to allow re-allocating SDRs to MDBs “seems very, very far away”, adding that if Germany and the rest of the Eurozone states feel unable to do this, they could issue their own bonds to offer cheaper capital for climate finance.

Songwe and Plant argue that, to avoid the same hurdle next time SDRs are dished out, MDBs should be given them directly rather than asking wealthy governments to re-allocate them. This would, however, require agreement from 85% of the IMF’s executive board, which is “no small feat in today’s politically fractured world”, the economists warned.

(Reporting by Joe Lo; editing by Megan Rowling)