This article will be updated throughout the day and an edited version will be sent out each evening as a newsletter – you can sign up here.

- Vulnerable nations storm out temporarily in protest at new finance text

- US accused of attempt to duck finance obligations

- Whispers of boost in climate finance goal to $300bn

- COP31 decision delayed, with Australia and Turkiye stalemate

Countries greenlight long-awaited rules for controversial UN carbon market

Around 9pm local time on Saturday and with finance talks still grinding on into overtime, the COP29 presidency gathered negotiators in a plenary to approve a series of less contested issues.

Many were technical or administrative – but among them countries finally agreed a package of rules for a global carbon market to be set up under the Paris Agreement, a deal that has been nearly a decade in the making.

The newly adopted rules create two different types of markets, where countries will trade emissions reductions and discount them from their NDC climate plans. The first – known as Article 6.2 – regulates bilateral carbon trading between countries, while Article 6.4 creates a global crediting mechanism for countries to sell emissions reductions.

COP29 President Mukhtar Babayev said Saturday night’s decision ended “a decade-long wait and unlocked a critical tool for keeping 1.5 degrees in reach” – but experts were critical of the integrity of the adopted rules.

In particular, they warned, the rules for bilateral trades under 6.2 could open the door for the sale of junk carbon credits – one of the weaknesses of the previous crediting mechanism set up by the UN known as the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM).

“The flaws of Article 6 have, unfortunately, not been fixed,” said Isa Mulder, a policy expert at NGO Carbon Market Watch. “It seems countries were more willing to adopt insufficient rules and deal with the consequences later, rather than prevent those consequences in the first place.”

Kelly Stone, coordinator of the Climate Land Ambition and Rights Alliance and senior policy analyst with ActionAid USA, described carbon markets that enable emissions offsetting as “essentially permits to continue polluting”.

“Nothing in the rules developed here will prevent carbon markets from repeating their history of harming communities and failing to deliver meaningful climate action,” she said.

Kristin Qui, a climate negotiator from Trinidad and Tobago and a former member of the Article 6.4 Supervisory Body which developed the UN carbon market standards, wrote in an oped for Climate Home this week that safeguards established for the market, under the “Sustainable Development Tool”, will require projects to follow both local laws and international standards, with Indigenous rights at the centre. “This dual approach ensures comprehensive protection, respecting local customs while adhering to global best practices,” she said .

When it comes to the adopted bilateral trading rules, one key problem is that they offer little accountability, said Jonathan Crook, another analyst from Carbon Market Watch.

He noted that countries will not be required to submit key technical information about their deals before making actual trades, and it could end up being published “possibly years” after the issuance of the carbon credits.

Vulnerable nations storm out temporarily in protest at new finance text

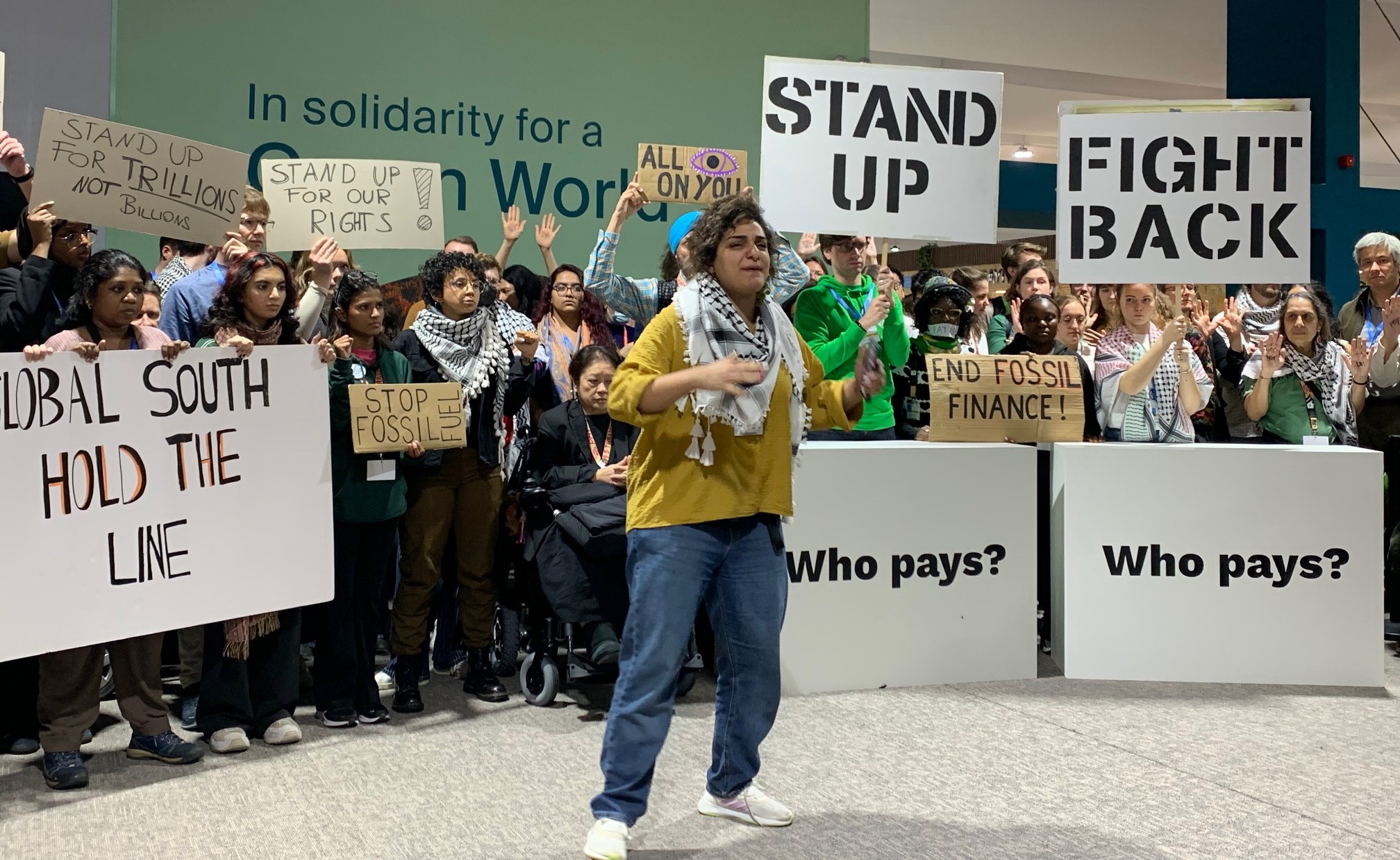

After the COP29 presidency handed out copies of a new finance text on Saturday evening and asked governments to discuss it, the world’s most vulnerable countries stormed out of the room in protest.

The text, which has not yet been published, included a climate finance goal of $300 billion a year by 2035, according to Panama’s special representative on climate change Juan Carlos Monterrey Gomez. Developing countries have countered with a yearly $500 billion by 2030, he said.

Two sub-groups of developing countries – the world’s Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS) walked out of the meeting to discuss the text in protest.

The LDC chair and negotiator from Malawi, Evans Njewa, told the room that: “This paper does not give us the ambition that we are looking for as the most vulnerable countries.” In particular, he said it does not give LDCs and SIDS minimum allocations of finance – they asked for $220bn exclusive for LDCs and $39bn for SIDS – or sub-goals for adaptation and loss and damage.

LDC & AOSIS just walked out of consultations as they don’t see their priorities reflected on the working text. pic.twitter.com/SA0zcSS9af

— Juan Carlos Monterrey (@theeco_nomist) November 23, 2024

“We have already said that we are not ready to associate with this paper and our sitting in here means nothing to us – if you want to continue discussing on this paper, then you can do so – this will allow us to leave this room – when you are done maybe you call us back”, he said on a video seen by Climate Home. A SIDS source in the room said that their delegation had made a similar speech.

Both negotiating groups then left the room and gathered in another room across the hall and the meeting was suspended. The G77 group of developing countries (without LDCs and SIDs) gathered in one room while developed nations stayed where they were.

The US’s climate envoy John Podesta left shortly after, encircled by TV cameras and heckled by an American protester who shouted that he was “selling out” green groups and had “no progressive credentials”. He told reporters he hoped it was the “storm before the calm”. Germany’s climate envoy Jennifer Morgan strode quickly back to her delegation office, without answering questions from the media.

The LDC chair Njewa confirmed that his group had not quit the talks. “We’re still here, we want to engage,” he posted on X. “We want to send a strong signal that we should not and cannot be ignored. We’re here to be part of the process and its important that we’re included in the process”. The chair of the island-states negotiating group AOSIS made a similar statement.

Colombian environment minister Susana Muhamad told reporters that an agreement was still possible. “With negotiation, we can get there,” she said, but she added that “the timing is very short” and “I would encourage the [Global] North to step up.” Asked about how the talks could be moved forward, Panama’s Gomez replied: “Ask the [COP29] Presidency. It’s not very clear what the next steps are.”

Panama’s special representative on climate change Juan Carlos Monterrey Gomez talks to journalists after finance talks were suspended on November 23, 2024, at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan. (Photo: Megan Rowling)

US accused of attempt to duck finance obligations

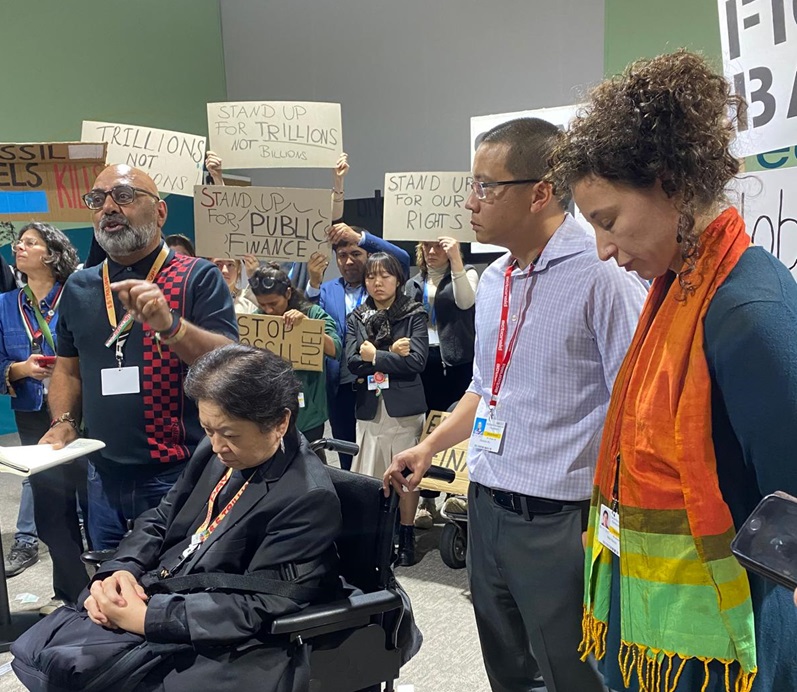

Climate justice campaigners pointed on Saturday afternoon to what they said was an attempt by the United States in Baku to sidestep its legal obligations under the 2015 Paris Agreement to provide finance to help developing nations tackle climate change.

They highlighted wording in the latest version of the proposed deal on the new post-2025 climate finance goal (NCGQ), due to be agreed this weekend at COP29, which they said implied finance from developed countries could be provided on a voluntary basis, and as part of a broad pool of any country that wants to contribute, rich or poor.

“The world’s biggest historical polluters are trying to use devious legalese to get a free pass from all responsibility. This interpretation would pull the rug out from under developing countries,” said Teresa Anderson, global lead on climate justice at ActionAid International. The US delegation did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

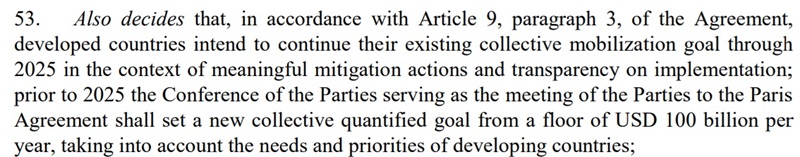

Friday’s draft finance text – the latest official version – says that governments decide to set a goal “in extension of paragraph 53 of decision 1/CP.21, with developed country Parties taking the lead” to $250 billion a year by 2035.

Paragraph 53 of the Adoption of the Paris Agreement decision (Screenshot)

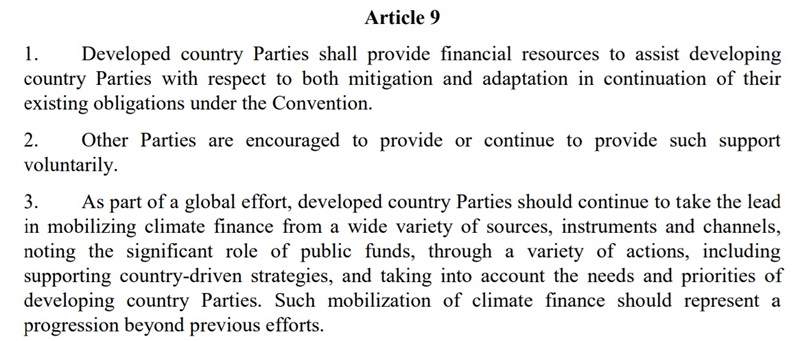

This paragraph 53, part of a decision accompanying the Paris Agreement, says countries intend to continue their existing $100bn a year collective goal through 2025 and shall set an NCQG from that floor “in accordance with” Article 9.3 of the agreement.

Article 9.3 notes that “as part of a global effort”, developed countries “should continue to take the lead in mobilizing climate finance from a wide variety of sources, instruments and channels”.

This is weaker than having a legal obligation to do so – which is laid out in the Paris Agreement’s Article 9.1 on climate finance. Article 9.1 says developed countries “shall provide financial resources to assist” developing countries to cut emissions and adapt to climate change. Article 9.2 says other countries are encouraged to contribute only on a voluntary basis.

Article 9 of the 2015 Paris Agreement (Screenshot)

Activists at COP29 said the US team’s lawyers have been arguing that a reference to this Paris decision text in the latest NCGQ draft in Baku means the US would not have a legal obligation to provide climate finance as defined under Article 9.1 but rather a weaker moral duty under 9.3 with developed countries “taking the lead” alongside all other nations.

Nikki Reisch, director of the climate and energy programme at the Center for International Environmental Law, said “we shouldn’t be fooled” by the US trying to claim that the NCQG conversation in Baku is about Article 9.3 of mobilising finance.

“Article 9.1 of the Paris Agreement is crystal clear that the Global North developed countries have an obligation to provide financing … there’s no question,” she emphasised.

A new, informal version of the NCQG text circulating on Saturday afternoon attempted to address some of the concerns on this point by including a new reference in the paragraph on the core $250bn goal to Article 9 of the Paris Agreement.

But Brandon Wu, director of policy and campaigns at ActionAid USA, said this was “not good enough”. “It doesn’t refer specifically to providing climate finance instead of mobilizing. And so we’re still here saying no deal is better than a bad deal and what’s on the table is a bad deal,” he added.

Campaigners said US negotiators were seeking a weak finance agreement at COP29 even though the US is expected to exit the Paris Agreement once President-elect Donald Trump takes office in January, as he has promised to do.

Asad Rehman, director of global justice organisation War on Want, told journalists, “there’s no difference between what President Biden is enabling here and what President Trump is doing – this is still two sides of the same coin.”

The core government-led goal of $250 billion has been proposed as part of a wider goal of at least $1.3 trillion a year by 2035 “from all public and private sources”.

Asad Rehman, Lidy Nacpil, Brandon Wu and Nikki Reisch speak to journalists at COP29 on Saturday 23/11/24 (Photo: Joe Lo)

Whispers of boost in climate finance goal to $300bn

As tension started to build in Baku for the end-game of the COP29 climate summit around midday, reports emerged that developed countries would be willing to raise their offer for the core of the new climate finance goal from $250 billion to $300 billion a year by 2035.

On Friday, the COP29 presidency released a draft text for a deal on the goal, known as the NCQG, with a number of $250bn a year by 2035, which provoked anger and dismay among developing countries, especially the African Group and small island states.

Sources with knowledge of the closed-door discussions told Reuters the European Union, the US, Australia and the UK had indicated they could accept the higher number.

Immediate reactions were not forthcoming from developing countries, who are discussing their strategy. But $300bn a year is only around half of what the G77 group of all developing countries have been seeking in government finance.

It’s also less than the $390 billion by 2035 that Brazilian environment minister Marina Silva proposed in a press conference late on Friday night. That figure is from a report by a UN-commissioned group of top economists.

Power Shift Africa campaigner and economics professor Fadhel Kaboub said $300 billion is “still not good enough”.

COP31 decision delayed, with Australia and Turkiye stalemate

Governments in the UN’s “Western Europe and Others group” have been unable to reach consensus on where to hold the COP31 climate summit in 2026.

Turkiye and Australia are both bidding for it and, despite a meeting between the two countries’ climate ministers last week, neither have backed down. The decision will now be made at the annual climate talks in Bonn in June or at the COP30 talks in November.

Australia wants to co-host the summit alongside at least one Pacific nation, with Adelaide and Sydney the most likely destinations. Turkiye is hoping to host it in the southern tourist hotspot of Antalya.

Australia will have national elections by May at the latest, before the Bonn talks in June. It is possible that the current centre-left government could lose power to a more right-wing government.

Thom Woodroofe, senior international fellow at Australia’s Smart Energy Council, said that “when Australia sets its diplomatic sights on big and important things, it can make them happen”. “Hosting a COP will help to focus Australia’s transition to a decarbonised economy and clean energy export superpower,” he added in a statement.

Bahar Ozay, coordinator of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network in Turkiye, said the country has good air transport links and that hosting COP31 will “create a significant and timely leverage” for the green transition. She added that Turkiye was “not an oil and gas exporter”.

Criticism has been levelled at recent COP host nations for their high levels of fossil fuel production and exports. Australia was the world’s largest exporter of liquified natural gas in 2021, according to BP’s statistical yearbook.

Turkiye wants to host COP31 in its tourism capital Antalya, which will be in its tourist off-season with temperatures of 10-20C (Flickr/ Naval S)