When Jimoh Abeeb first heard about using compressed natural gas (CNG) to run cars back in 2022, he didn’t think much of the idea. A friend had just adapted his vehicle for CNG and was encouraging him to do the same.

“When he told me that I was going to use up to N450,000 ($282) to convert my car to CNG, I just lost interest,” Abeeb told Climate Home.

But the following year, the Nigerian government removed its fuel subsidy, causing petrol prices to rocket from about N250 ($0.16) a litre in March 2023 to N1,180 ($0.74) in October 2024.

The Abuja-based civil engineer quit his job at the start of 2024 to go freelance but towards the end of the year, he was struggling to afford his usual petrol bill of about N250,000 ($157) a month as he crisscrossed the city to work on different construction sites. “I was using 50 percent of my monthly earnings just to fuel my car,” Abeeb said.

So in October, he spent N800,000 ($502) to convert his vehicle to run on CNG. For just N3000 ($1.88), he can now fill his cylinder which lasts for three days and covers 150-200 kilometres. “It is a game changer,” Abeeb said.

Across Africa, growing numbers of drivers are doing the same. This is evident in the long queues of people waiting in line to refill their CNG cylinders in countries such as Tanzania and Nigeria, as the supply network struggles to keep pace with surging demand.

Leap in CNG use

Mordor Intelligence estimates that the African market for vehicles powered by CNG and LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) is expected to grow 7% a year between 2025 and 2030, with most of the growth in CNG.

Some African governments are supporting this expansion. Nigeria, for example, has launched a Presidential CNG Initiative (Pi-CNG) to “provide succor to the masses” due to the hardship caused by the fuel subsidy removal and to deliver a “cleaner alternative” to petrol and diesel.

In some states, it provides free conversion for commercial drivers and a 50-percent discount for ride-share vehicles. Last July, the country’s state-owned oil company commissioned a dozen CNG stations in major cities, while constructing 35 more across the country.

Over in East Africa, the Tanzanian government has also invested in CNG stations and is partnering with private companies to fast-track infrastructure development. Additional support includes certifying retrofitting workshops and eliminating duties on CNG equipment and conversion kits to make adoption more affordable for businesses and individuals.

Vehicles queue at a CNG filling station in Abuja, Nigeria

Also, in late 2024, the Egyptian government announced the roll-out of a national initiative to convert 1.5 million vehicles to CNG this year. Prime Minister Moustafa Madbouly said it would reduce carbon emissions and cut fuel costs for citizens.

The environmental benefits of this African shift to gas for transport are, however, hotly contested. CNG is a fossil fuel – natural gas – where the gas has been compressed so that it can be stored in high-pressure cylinders for use in vehicles. Critics say that its deployment will detract from efforts to run vehicles on clean electricity.

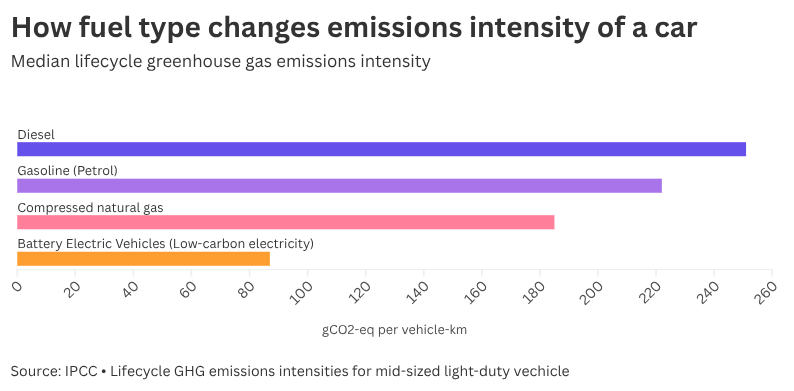

But CNG does produce less exhaust and greenhouse gas emissions than motors running on gasoline or diesel oil.

These qualities make it a viable energy transition fuel for Africa, said Michael David Terungwa, climate advocate at the Global Initiative for Food Security and Ecosystem Preservation (GIFSEP). As well as being “cleaner” than petrol, it is also more affordable, given price increases and poverty levels on the continent, he added.

Still a fossil fuel

But Lorraine Chiponda, Africa coordinator at the Global Gas & Oil Network, argued that adopting CNG for vehicles will lock Africa into using climate-polluting fuel for transport. She said the conversion is “misguided”, adding that fossil fuel firms are trying to “greenwash people into believing that gas is cleaner”.

With governments setting net zero targets – like Nigeria’s for 2060 – they must eventually phase out fossil fuels, she argued, thereby making Africa’s CNG adoption “both short term and short-sighted”. “Seeing African countries adopting technologies that will soon be redundant is not the transition that we are aiming for,” she added.

Africa should instead be negotiating green technology transfer – for the production of batteries, chargers and electric vehicles (EVs) – with richer nations including China, as well as mobilising public and private investment, Chiponda said.

Arctic geoengineering experiment shuts down over environmental risks

Interest in EVs is increasing across Africa and countries are preparing to electrify transport, albeit at a slow pace. A report by the global think-tank Energy for Growth Hub found that many African countries are lagging, with only a quarter of those analysed – like Morocco and South Africa – demonstrating high readiness for EV adoption.

But even in those places that are most advanced, the challenges of weak electric grid infrastructure, limited access to finance and low incomes limit EV potential, the report says.

A CNG retrofitting workshop in Port Harcourt, Nigeria (Photo: Vivian Chime)

In Nigeria, “if you have an electric car, where are you going to charge it?” Terungwa asked. “Also if you look at the average cost of an electric vehicle, we cannot afford it,” he said, adding that until these issues are addressed, CNG offers more economic benefits.

What African countries need to transition to electric transport systems is huge investment in EV manufacturing rather than importing goods and equipment, he noted. “Global North companies should set up factories for the production of batteries and the manufacturing or assembling of EVs – that way, it will become cheaper,” he added.

Shell dodges paying compensation for sham carbon credits in China

Energy and industry consultant Elizabeth Obode said drivers are interested in CNG because it is cheaper rather than “cleaner”. The high cost of EVs, coupled with a lack of good roads, charging stations and repair workshops, “is the huge killer” for EV adoption, so that even if African countries wanted to shift entirely to EVs and ban CNG vehicles in the next decade, they would struggle to do it, she added.

Obode said that to encourage EV adoption, African governments need to incentivise the private sector to invest by offering tax breaks and other financial support for battery production, charging stations and EV manufacturing.

She and Terungwa agreed that countries should plan a time-frame to move away from CNG. Obode said governments can work with their net-zero emissions targets “to help determine what is realistic in terms of transitioning away from CNG use”.

(Reporting by Vivian Chime; editing by Joe Lo and Megan Rowling)