Celebrations at UN headquarters, despondency on the streets of Kinshasa.

News the Paris climate agreement was on its way into force had diplomats popping the corks in New York, but in the Democratic Republic of Congo capital there is simply frustration.

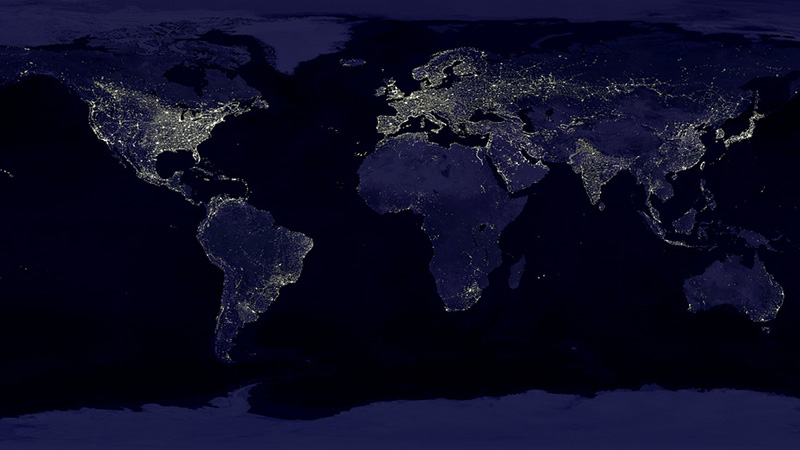

The world’s poorest countries are energy starved, with an estimated 1.3 billion in countries classed by the UN as “least developed” lacking regular and predictable access to power.

Globally 1.1 billion people do not have access to electricity, and 2.9 billion cook their food and heat water on dirty, polluting and inefficient stoves.

In a week when leading politicians in Washington DC, Brussels and London basked in their collective glory of the 2015 Paris pact, their African counterparts were working on a plan to light a bulb.

Launched this week in Kinshasa, the LDC Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Initiative (REEEI) for Sustainable Development is a mouthful of a project, the latest in a stream of similar plans.

In late 2015, the Africa Renewable Energy Initiative was announced, although closer examination suggests this was a repackaging exercise with no new money and based on existing projects.

The aim of REEEI said Tosi Mpanu Mpanu, a Congolese diplomat who is lead envoy for the world’s poorest at UN climate negotiations, is to “leapfrog fossil fuel-based energy”.

As a major UN climate meeting in Marrakech draws close, Mpanu Mpanu argued the best change yet for the world’s rich to “fulfil their support responsibilities under the Paris Agreement”.

That’s a long way of saying money and access to better forms of technology like cheaper solar panels, LED lamps and wind turbine designs.

Africa files: the best reporting on the continent’s climate crisis

There are projects aplenty out there working in Africa: the US, EU and UK all have schemes to promote cleaner forms of power. India and China are also taking an interest.

But lighting up a continent takes time, as this year’s main report by the UN-backed Sustainable Energy For All programme illustrates.

“Progress on energy efficiency is at two-thirds the required rate. We need to double the share of renewables in the energy mix,” it read.

“Finance flows are at one-third of the $1.0-1.2 trillion per year required to meet all three of SEforALL’s objectives by 2030.”

The organisation’s chief Rachel Kyte oozes positivity and a can-do attitude when asked about a goal to deliver universal energy access to everyone in the next decade.

“Don’t tell me it can’t be done,” she told a New York audience last month. But a look at the cash on offer to make this happen tells a story.

UN energy chief: Universal energy access possible by early 2020s

Updated climate finance data from the Climate Policy Initiative reveal that of the US $392 billion deployed in 2014, $10bn made it to sub-Saharan Africa, $9bn to North Africa.

On average, the CPI estimates $41bn was transferred from countries in the Global North to those in the Global South through 2013 and 2014. $10bn was classed as “South-South” investment.

Developing countries are seeing rising flows of green capital entering their economies, but as the CPI analysis shows, the bulk is heading for China, India and other South Asian countries.

It’s a bigger issue than it may seem. African emissions are small, and thus have little bearing for now on whether the world avoids warming above the 1.5C/2C danger zone.

But ignore a continent’s demands for the access to power enjoyed elsewhere and “they will have to turn to fossil fuels for their only response,” said Christiana Figueres, ex UN climate chief.

(Source: SE4ALL annual report 2016)

There are plans afoot: many rich countries are banking on the Green Climate Fund to deliver a shot of adrenaline into funding flows to LDCs and Africa.

Formally launched in 2015 with $10 billion of pledges, it has failed to impress, wracked by in-fighting among board members and searching for a new chief executive.

The next GCF meeting runs from 12-14 October, and will consider requests for $786 million of funding across 10 projects. Progress of sorts, but hardly transformational.

Report: Green Climate Fund urged to blacklist coal-funding agencies

One issue GCF insiders complain of is the lack of adequate projects they are being asked to consider, hence the relatively small pipeline of approved initiatives through 2015 and 2016.

It’s a problem veteran diplomats like Jagdish Koonjul, Mauritius ambassador to the UN and chair of the Alliance of Small Island States from 2002-2005 say has been lingering for decades.

Mauritius has twice applied for funds from the GCF and twice been rejected, said Koonjul.

“We have been screaming about it – LDCs have a major problem on capacity and transfer of technology,” he tells Climate Home.

“Many of us don’t even know if there’s a technology that’s will help us. If we know we don’t know where to get it. If we know where to get it we don’t know where to get the funds.

“Go try and access those funds. It’s a nightmare. Procedures are so complex. In the end who is benefitting? The big ones: they have the capacity to make these bankable projects.”

Weekly briefing: Sign up for your essential climate politics update

One solution is for smaller developing countries to club together, an idea being pioneered by the 53-strong Commonwealth of Nations.

Last month it launched a hub to draw in expertise from all its members, with the goal of delivering copper-bottomed funding proposals to the GCF and other development banks.

“There are billions purportedly available but no-one has been able to draw down on it,” said Baroness Scotland, a former UK government minister who is now Commonwealth secretary general.

“What we realised is that in the Commonwealth there are many small states making inroads to get climate finance and they are not succeeding… we need critical mass.”

That’s not, she added, to let wealthy nations off the hook for the $100 billion a year they promised to deliver by 2020, a promise that has yet to get close to being honoured.

“There’s one thing to make a commitment when no one is going get the money… it’s another to make a commitment and deliver,” she said.

High and dry: African drought leaves Lesotho parched. @SiphoMcD reports from Katse https://t.co/inXFFvzfef #Africafiles pic.twitter.com/yxP6WzIwdy

— Climate Home News (@ClimateHome) October 6, 2016

There are increasing reasons to be positive about global climate finance flows, argues Mafalda Duarte, manager for the $8.3 billion Climate Investment Funds (CIFs).

South Africa, Egypt, Pakistan, Argentina and Morocco are some of the countries her organisation is working with to de-risk clean energy projects like the Noor concentrated solar power plant.

Her officials are also embedded with governments from Kazakhstan to Tanzania to advise on regulatory reform and develop adequate clean energy roadmaps.

But, she admits, Africa remains a problem. “We know there is a massive gap of equity investment in Africa… to a large extent it is a perception of risk and investors will require a higher return.”

The CIFs can deploy $5 billion and unlock $55 billion from the private sector, but, said Duarte, it’s the institutional investors like pension funds who “hold the key to the trillions”.

They have the capital to sink into longer term projects but risk appetites vary, and that’s where public funds from governments can help to ensure private investors don’t get badly burnt.

With myriad pressures on national budgets in the developed world, she adds a note of warning, framed around the global refugee crisis that dominated this year’s General Assembly.

“If we don’t tackle climate change… what we are observing this wave of refugee crisis it’s going to intensify,” Duarte said

“We need the political will and wisdom. Climate change is no longer about the long term. What do communities do if they have no way to sustain their livelihoods? They will migrate.”