Canada is doubling its contribution to the UN climate science panel to C$300,000 ($250,000) a year until 2022, environment minister Catherine McKenna announced on Saturday.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was on the brink of a funding crisis after president Donald Trump said he would end the US’ $2 million contribution, which accounted for 45% of the organisation’s budget in 2016.

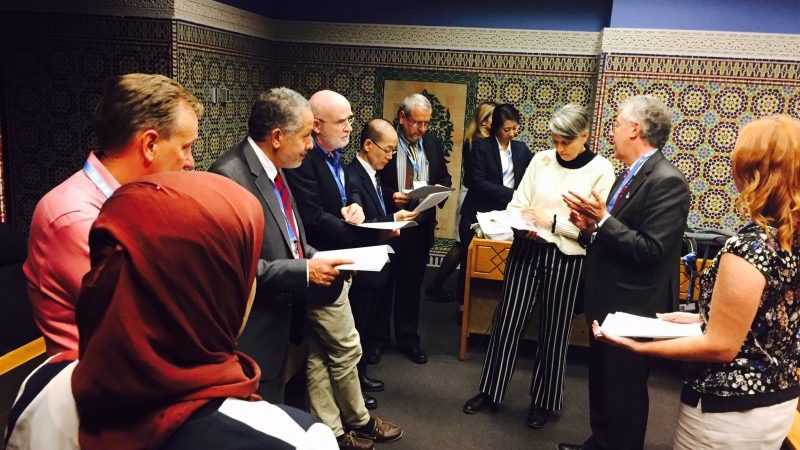

At a meeting in Montreal, other governments promised enough money to cover next year’s budget, a source familiar with the fundraising effort told Climate Home. At the time of writing, they had not revealed how much they were chipping in.

“I am proud of Canada for hosting governments and climate scientists from around the world this week in Montreal,” McKenna said in a statement. “By doubling our support for the important work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, our government will help climate scientists from around the world assess vital research, and give governments the tools to make smart, evidence-based decisions for our future.”

Patricia Espinosa, head of the UN climate negotiations forum, welcomed the move, tweeting: “Canada’s climate leadership is exemplary!”

Thank you! Important for us because @IPCC_CH science underpins @UNFCCC policy. #Canada‘s #climate leadership is exemplary! https://t.co/NMfAJrnKBP

— Patricia Espinosa C. (@PEspinosaC) September 9, 2017

The IPCC also found support from within the US Senate last week, with an appropriations committee amending its version of the budget to include the IPCC’s funding. The Senate will now wrangle with the House of Representatives, which sided with Trump on the issue.

The funding boost from elsewhere comes as the organisation embarks on what chair Hoesung Lee described as its “most ambitious work programme ever” in a webcast press conference.

Government representatives in Montreal agreed an outline for the next assessment report on the state of climate science, due out in 2021 and 2022.

It will cover improvements in the evidence base since the last reporting round in 2014-15, said Lee: “A good example is the huge advances made in understanding the attribution of extreme weather events. This is of course extremely relevant today, as we extend our thoughts and well wishes to those experiencing the consequences of Hurricane Irma in the Caribbean and Harvey so soon before.”

In response to demand from policymakers, there will be an increased focus on regional trends and a chapter on the social science of cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

Report: Irma forces Caribbean delegates to abandon UN climate science meeting

One of the tensest discussions, according to people at the meeting, regarded “loss and damage”. That is the jargon used in political negotiations to cover impacts of climate change that go beyond people’s capacity to adapt. For example, houses, infrastructure and crops flattened by tropical storms, where there is evidence global warming contributed to the destruction.

Small island states and some Latin American countries sought to include the phrase in chapter outlines, reflecting its status as a separate article of the Paris climate agreement. Many vulnerable communities are already facing losses, they argue, which should be clearly documented to underpin the political debate.

Others pushed back. At political negotiations, countries most responsible for historical emissions have resisted the loss and damage agenda, fearing it could open them up to compensation claims from those hit by global warming.

In the end, there was no explicit reference to loss and damage in the outline, but it covered more elements than the previous draft. These included irreversible losses from slow onset events like sea level rise, desertification and ocean acidification, as well as the risk of weather disaster.

“Although the small islands and others were forced to compromise and to not include the words ‘loss and damage’, they have secured some wording that covers key aspects of loss and damage and have guided authors towards literature on these aspects,” said Bill Hare, head of consultancy Climate Analytics, which supports island states.