One morning in October in Loitoktok, a picturesque town in southern Kenyan on the border with Tanzania, Emmanuel Maiyani sat with a colleague discussing tree seedling species, prices, and planting sites as they filled in an excel sheet for hours.

With 3.5 million Kenyan shillings ($35,000) in funding from WWF, Maiyani was busy planning a large tree-planting initiative later that month, where 300 members of the local community would plant 25,000 seedlings to restore 245 hectares (605 acres) of indigenous forest, set against the backdrop of majestic Mount Kilimanjaro.

Maiyani is a farmer and businessman who chairs one of Kenya’s 150 community forest associations (CFAs). These associations act as guardians of the country’s forests, protecting them from logging and environmental destruction, and provide rural communities with a reliable source of income and jobs.

“Loitoktok forest is my life. I am attached to the ecosystem and to the forest. I feel that I am indebted to protect and conserve it as I am passionate about it. This is purely a voluntary role and I am happy to continue offering my leadership to the wellbeing of this forest,” Maiyani told Climate Home News.

These forest communities were supposed to play an integral role in Kenya’s ambitious tree-planting scheme, but they say they have been sidelined, as the government struggles to achieve its goal. To curb deforestation and restore drought-stricken regions, Kenya set up a strategy in 2018 to increase its tree cover by two billion trees, to 10% of the national land mass by 2022.

With just over a month to go, Kenya looks set to miss its target by a long way, having planted just 300 million trees annually (1.2 billion trees in total), a spokesperson for the Kenyan Forest Service told Climate Home.

As part of its tree planting strategy, the government said it would include communities and provide them with grants for forest restoration. But a ministry official told Climate Home News that the fund is yet to be launched and that to date no associations have been granted funding.

Communities say they have been kept in the dark about the government’s plans and are forced to rely on non-profits to fund restoration projects.

“We are yet to receive any support,” said Maiyani. “If the government did [provide funding], that would really help us increase the income for members and also engage some members as forest scouts.”

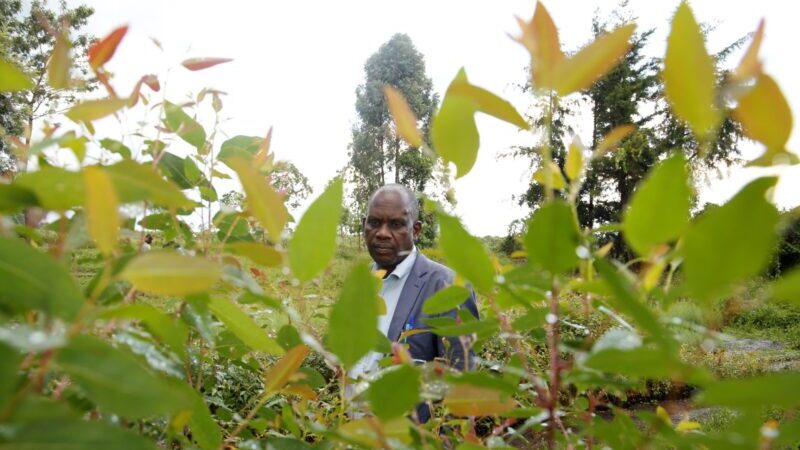

Emmanuel Maiyani, the chairman of Loitoktok forest association inspects a tree at a nursery in one of his member’s homesteads In Kenya (All photos: Anthony Langat)

When Kenya gained independence from Britain in 1963, 10% of the country was covered in forests. Over the past decade forest cover has fallen to 6%. Between 2001 and 2020, Kenya lost 361 kha of tree cover, equivalent to 176 Mt of CO2 emissions, according to Global Forest Watch data. Many of Kenya’s rural communities rely on wood fuel to heat their homes and cook with.

More intense and frequent droughts are exacerbating the situation, killing swathes of young trees across the country.

In 2018 the government banned all logging in the country as a response to drought. Two years later the ban was partially lifted for the “disposal of mature and over-mature forest plantations for an area not exceeding 5000 hectares.”

The tree planting scheme was envisioned to contribute to a 50% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from Kenya’s forestry sector, one of the aims of its 2030 climate plan.

A failure to meet the 10% target by 2022 means that Kenya is not on track for its 2030 climate goal, Sarah Kahuri, a forest information systems analyst and climate expert, told Climate Home News.

“The curbing of emissions by 30% was computed with reference to restoration of our ecosystems. It means as a country we are not going to achieve the commitments in our nationally determined contribution [to the Paris Agreement],” she said.

#mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; }

/* Add your own Mailchimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block.

We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */

Studies show that community forest associations play a vital role in ensuring the conservation and sustainable management of the country’s forests, by improving soil quality, reversing degradation and planting trees to sequester carbon.

The Kenya Forest Service has described the involvement of CFAs as the “only way of ensuring sustainable utilisation of forest resources.”

Since its formation in 2005, the Loitoktok community has been planting trees in areas which have experienced severe deforestation and land degradation. It now has close to 1,500 members, who engage in a wide range of conservation activities, including beekeeping, setting up of tree nurseries, ecotourism and restoring areas of the forest. Members can also pay 100 Kenyan shillings ($1) per month to graze their livestock in the forest.

Esther Leleito, a member of Chepalungu CFA, uproots her bean crop in a parcel of land allocated to her by the CFA

With government support, they could achieve much more, said Maiyani. “If they would just give us grants, it would help in running our CFAs and implementing the activities like better equipping our apiaries and establishing more tree nurseries.”

500 kilometres away from Loitoktok, lies Chepalungu forest, a lush, hilly landscape that extends for thousands of acres. The trees in the forest are young and there is a clear view of the town Siongiroi in the distance, where the iron-sheet roofs reflect the midday sun. In the forest, Joseph Towett, the chair of Chepalungu’s forest association, inspected newly planted seedlings, while members of the community harvested their beans nearby.

Towett recalled how the forest paid the price when the country sunk into post-election violence in 2007. Locals descended on it, evicting the forest guards and setting their offices and houses on fire. Once bare of trees, the forest was turned into rangelands for grazing the livestock. Together with other community members, Towett formed a CFA in 2012 to resurrect the decimated forest.

Towett has heard about the two-billion tree initiative from the media but told Climate Home that his CFA has not been consulted on its implementation or on how the community will be involved.

Instead the Chepalungu is relying on funding from WWF to carry out its restoration work, which includes fencing off areas of land, allowing them to regenerate, he said.

Joseph Towett, the chairman of Chepalungu forest association in a tree nursery in Kapchukbe block of Chepalungu Forest

The government tree-planting strategy states that 3 billion Kenyan shillings ($3 million) will be spent on the “protection of natural forests for natural regeneration.” This would involve fencing off degraded areas, allowing trees to grow without disruption.

“We haven’t received any funding directly from the Kenya Forest Service or government for fencing off for regeneration or tree planting,” Towett told Climate Home News.

A forest such as Chepalungu would greatly benefit from such funding, said Towett. “If we had enough funds to fence up the entire forest, this would help in ensuring that regeneration happens. Now it is unfenced and people graze their livestock inside the forest hence hindering regeneration,” he said.

To date the forest association has only managed to fence off 100 acres of 4,871 acres of land, almost all of which is degraded, through funding from non-profits.

The effects of the fencing are already visible. “Lately we have heard of sightings of leopards in the regenerated areas,” said Towett.

Read more climate justice stories

When the government rolled out its tree-planting scheme, it projected 48 billion Kenyan shilling ($428 million) as the cost for implementation. 3 billion Kenyan shillings ($27 million) was set aside for the “protection of public natural forests for natural regeneration,” in collaboration with the Kenya Forest Service and community forest associations.

The scheme also received support from the UN Development Programme, Food and Agriculture Organization and UN Environment Programme. Geoffrey Omedo a portfolio analyst at the UNDP, told Climate Home News that UN bodies are supporting this initiative as they recognise “the importance of unlocking new climate finance flows to support Kenya’s efforts in climate adaptation and mitigation.”

Kenya’s environment ministry told Climate Home News that the fund was not ready yet, but that it will be launched soon, without providing further details.

James Waikibia, an environmental activist doesn’t think this is the case. He believes that the country will not achieve the target of two billion trees by next year, citing corruption and the government’s decision not to involve local communities.

“The communities haven’t been adequately involved in the practice. If the community doesn’t own a project, then the trees being planted in their area will not receive protection,” he said.

Timonthy Oindi, a forester with the Kenya Forest Service in charge of Chepalungu Forest reprimands a woman found chopping down trees for firewood

“We do receive support from the Kenya Forest Service with regards to the nursery and other activities. However, we haven’t received any support specifically for the two billion tree initiative,” said Towett.

The Kenyan government has missed an opportunity by choosing not to involve local communities in its tree-planting scheme, according to forest analyst Sarah Kahuri.

“When we involve the forest community they also do public policing. They ensure that the bad guys do not come in and cut trees illegally and they know themselves better than the forester who may not know the good and the bad guys,” she said.

Dr Elizabeth Wambugu from the Kenya Forest Service helps communities establish forest associations and manage these areas sustainably. She told Climate Home that CFAs play a critical role when it comes to forest enforcement.

“Through bylaws that they have put in place, the communities ensure enforcement like levying fines on members if their livestock trespass into forest areas which are non-grazing forest areas,” she said. “They also provide security through forest scouts from within the community.”

They enjoy a close relationship with the Kenya Forest Service, who buy their tree seedlings.

“We buy seedlings from them for between thirty shillings to fifty shillings per seedling and this provides an income to the communities that we work with,” Wambugu said.

Both Towett and Maiyani said they are disappointed by the government’s decision not to partner with forest communities, as promised. “All this is a pipe dream if there is no support for the community. Support should go directly to the community for impact to be seen,” said Maiyani.

This article is part of a climate justice reporting programme supported by the Climate Justice Resilience Fund.