Governments should promise in their next round of climate plans, due by early next year, not to build any new coal-fired power stations and to shut down existing ones early, the head of the International Energy Agency (IEA) has said.

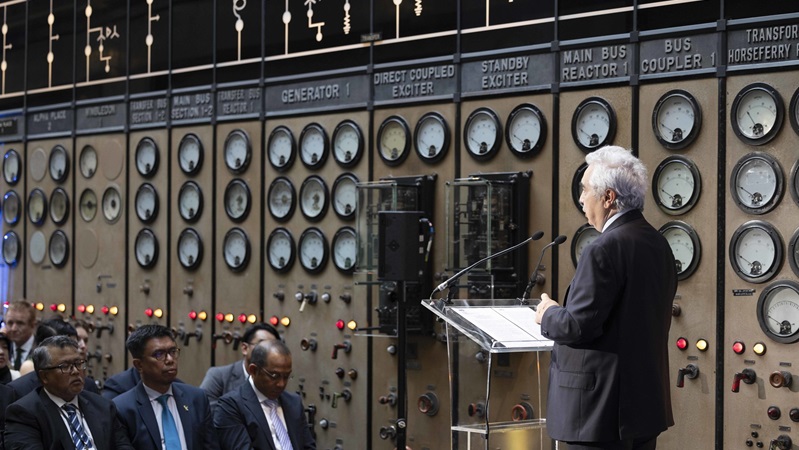

Speaking on Monday at an old London coal power plant-turned-shopping centre, IEA head Fatih Birol said he would be “very happy” to see new NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions) that “include no new unabated coal and also early retirements of existing coal”.

In 2021, the Glasgow Climate Pact, agreed at the COP26 UN climate summit, called on countries for the first time to accelerate efforts “towards the phase-down of unabated coal power”. “Unabated” means power produced using coal without any technology to capture, store or use the planet-heating carbon dioxide emitted during the process.

Birol, a Turkish energy analyst, said that stopping coal-plant construction was “as our North American colleagues would say, a no-brainer”. Yet, he added, while “the appetite to build new coal plants is in a dying process, some countries still do it”. He singled out China’s plans to build 50 gigawatts (GW) of new coal plants.

Shutting down existing coal plants, particularly young ones in Asia, is more difficult because the companies that have built and operate them would lose money, Birol noted. There is almost $1 trillion of capital to be recovered from existing coal plants, “so who is going to pay for this?” he asked, calling it “a key issue”.

Birol praised the Just Energy Transition Partnerships that have been set up between wealthy countries and several coal-reliant emerging economies like South Africa and Indonesia to help address the problem. He added that “there are some countries in Asia who can, in my view, afford to retire their coal plants earlier”, without mentioning which.

Malaysia’s Deputy Prime Minister Fadillah Yusof announced at the event organised by the Powering Past Coal Alliance, which includes 60 countries, that Malaysia aims to reduce its coal-fired power plants by half by 2035 and retire all of them by 2044. It will also tackle social and economic challenges through reskilling programmes for workers and promoting renewable energy adoption, he added.

Speaking later at London’s defunct Battersea power station, Indonesia’s deputy minister for maritime affairs and investment, Rachmat Kaimuddin, explained some of the challenges his country faces in phasing out coal.

Kaimuddin (right) speaks alongside Germany’s climate envoy Jennifer Morgan (centre) in London on June 24, 2024. (Photo: Powering Past Coal Alliance)

After China and India, Indonesia has the world’s biggest pipeline of new coal power plants under construction. Kaimuddin said the state energy company would not build any more but added that cancelling existing contracts is “very, very difficult” unless the company constructing the plant wants to pull out – which none have yet.

In addition, shutting down existing power power plants is expensive, he said, because many coal power plants have “take or pay” contracts signed in the 1990s under which the government pays them whether their electricity is required or not.

Another concern is that the Southeast Asian nation does not want to lose its energy security in the switch to renewables, Kaimuddin noted. Indonesia currently mines domestically most of the coal it uses. “We’re trying to partner with other people to try to build [a] renewable supply chain in the country,” he said.

Millions of people in Indonesia work in the coal industry, he added, so a shift towards clean energy will need to include new jobs for them. “It doesn’t have to be green jobs – it has to be jobs, right?” he said.

Singapore’s climate ambassador Ravi Menon told the same event that the economies of China, India and Indonesia are growing and so are their energy needs, meaning that renewables have to be rolled out rapidly to meet demand.

Energy storage is also required to smooth intermittent supply from solar and wind, while electricity transmission infrastructure, including power lines, is needed to transport power from solar and wind farms to cities that account for a large share of consumption.

Both Kaimuddin and Menon said carbon credits should be used to offset losses for the owners of coal plants that are shut down early. “Retiring [plants] definitely will destroy financial value and… and we also need a better way to compensate them,” said Kaimuddin.

The event’s focus on coal raised concerns among some campaigners. Avantika Goswami, climate lead at the Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment, told Climate Home that “singling out coal” in the NDCs, rather than including fossil fuels more broadly, “equates to giving a free pass to oil and gas-dependent countries, many of whom are wealthy”.

It could penalise many developing countries, where coal is a cheap source of fuel and energy needs are still growing, she warned.

“A global climate policy that allows unfettered use of oil and gas – which together account for 55% of fossil fuel emissions – is incomplete and inequitable,” she added.

Romain Ioualalen, global policy lead at advocacy group Oil Change International, said the IEA’s head should know that “the time to focus only on coal as a climate culprit is over”. He pointed to a subsequent agreement at COP28 last year where governments agreed to “transition away” from fossil fuels in their energy systems, without setting a deadline.

“We need a full, fast, fair, funded phase-out of all fossil fuels. Setting such a low bar for ambition is out of touch and inequitable, keeping the door wide open for major oil and gas producers,” Ioualalen added in a statement.

He called on rich countries that are “most responsible” for the climate crisis to foot the bill for a just transition. “We know they have more than enough money. It’s just going to the wrong things like fossil fuel handouts,” he said.

(Reporting by Joe Lo; editing by Megan Rowling)

This story was updated after publication to include comments from Avantika Goswami at the CSE and Romain Ioualalen at Oil Change International,.