The emerging market in nature protection was all over Cali during the just-ended COP16 UN biodiversity summit, with new guidelines for biodiversity credits launched on the sidelines and campaigners pushing back against the idea.

The so-called “biodiversity market” has risen in importance since the landmark Global Biodiversity Framework pact, adopted at COP15 in Montreal in 2022, which calls on countries to “stimulate” innovative finance options for nature including “biodiversity offsets and credits”.

Some experts told Climate Home the hype around an unregulated biodiversity market could repeat the mistakes of the voluntary carbon markets, whose reputation is in tatters after being plagued with revelations of exaggerated emissions reductions and social problems. Others consider the new biodiversity market as a viable way to channel private finance into nature protection and restoration.

COP16 hands power to Indigenous people but fails to bridge nature finance gap

At COP16, platforms to support the “biocredit” market were launched. An advisory panel led by the UK and France presented a framework to transact “high-integrity” credits, while carbon-offset registry Verra launched its own framework for developing nature credits.

Biodiversity credits finance projects that conserve, manage or restore key ecosystems. One in Ireland sold €2 million ($2.15 million) worth of credits by planting 600,000 native trees, for example, while another in Australia sold an undisclosed amount of credits to the global bank HSBC for improving water quality in the Great Barrier Reef.

A new report by market research company Morningstar Sustainalytics shows that global assets held in funds aiming to boost biodiversity have more than doubled over the past three years, reaching $3.7 billion in 2024. The market is still small compared to climate-related assets estimated at $520 billion.

“Nature-positive”

Unlike in the carbon market, there is a difference between biodiversity credits and offsets. In the biodiversity market, biodiversity credits are “nature-positive”, meaning that companies pay for contributions to protecting nature without necessarily compensating for harmful impacts from their own supply chains. They get a reputational benefit in exchange, such as being able to brand their products as biodiversity-friendly.

But the Campaign for Nature has warned that such credits could detract from a pledge by governments to provide $20 billion by 2025 for nature conservation in developing countries, if they believe that “somehow ‘innovative finance’ from the private sector will play a significant role” in meeting that goal. In a paper, the NGO said voluntary private finance would not be enough.

Another part of the fledgling market – biodiversity offsets – came under even more fire from activists at COP16. These are used when a company does damage to biodiversity in one place, and makes up for that impact in a different place – for example by planting native trees or reducing pollution in ecosystems.

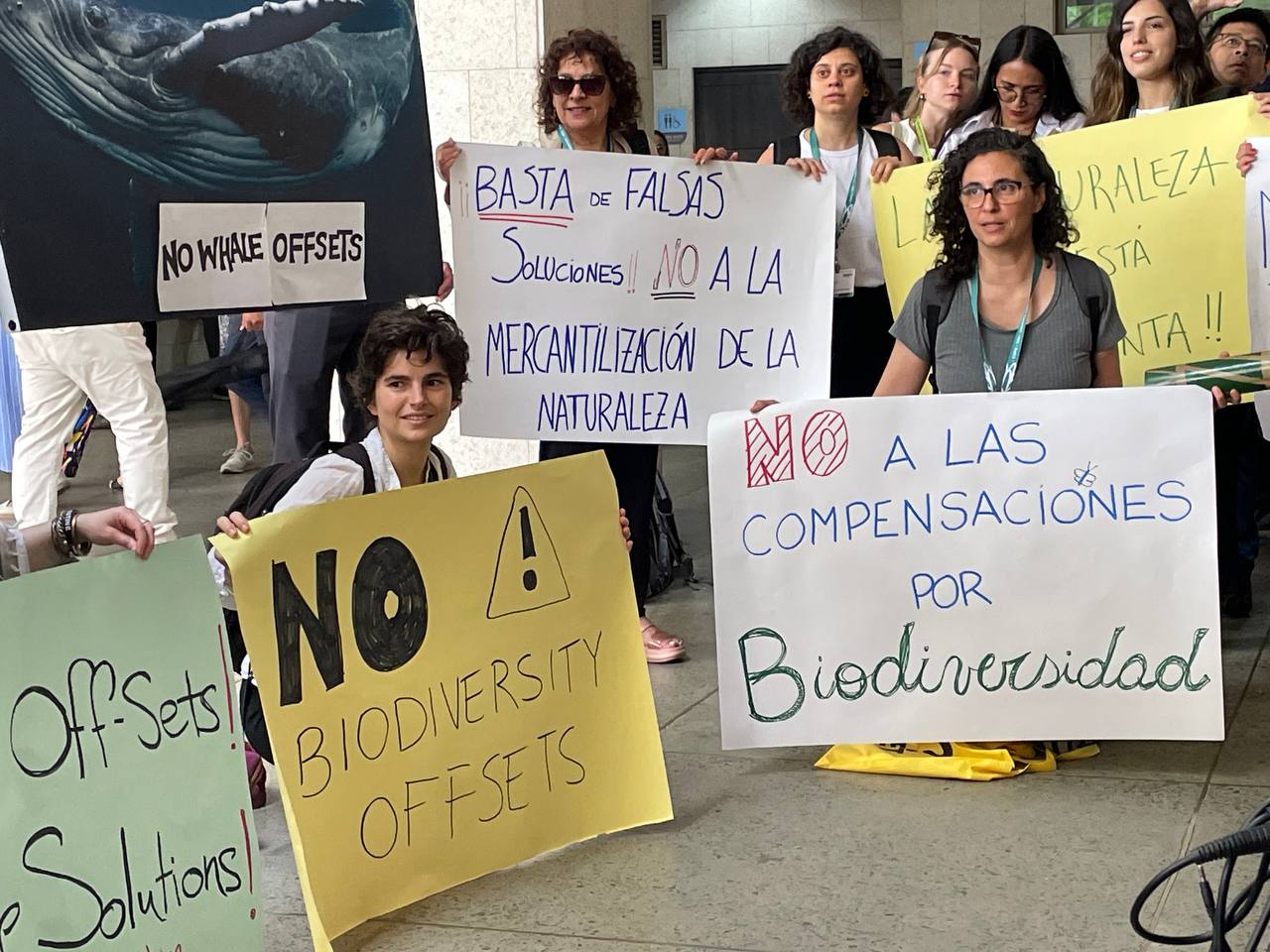

At the start of the second week of COP16, multiple green groups staged a demonstration against biodiversity offsetting and crediting, arguing that it “destroys nature and undermines the rights of peoples”.

Nele Marien, from Friends of the Earth International, said the system is seen as deeply flawed, because proper restoration of ecosystems would take too long. She also questioned whether there is enough available land with the right conditions for offsetting.

“You are destroying one ecosystem and you’re rebuilding something somewhere else, which takes decades and which really is never going to be up to the level of the original ecosystem,” Marien said.

At COP16, countries clash over future of global fund for nature protection

International guidelines

Anna Ducros, a researcher at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), said offsets are a “distraction” from biocredits, which – if designed correctly – can be “genuine impactful investments” by the private sector.

The International Advisory Panel on Biodiversity Credits (IAPB), launched by the British and French governments, is one of the main initiatives aimed at achieving “high-integrity” biocredits.

The body presented its first results at COP16, announcing a set of guidelines for transacting credits in the biodiversity market. One of the key recommendations is that Indigenous people should be co-owners of projects, and participate in their design and delivery.

Asked about potential similarities between the carbon and biocredit markets, Amelia Fawcett, co-chair of the IAPB, said the new framework for biocredits builds on lessons from carbon-offsetting, adding that conversely “the carbon market can learn a great deal” from work on the biocredit market so far.

The biodiversity market has quickly developed ways to assess the impact of projects, at times collaboratively with Indigenous people. Measuring the benefits of biodiversity credits is “complex but feasible”, noted Sylvie Goulard, another IAPB co-chair.

The IAPB’s framework advises against adopting a one-size-fits-all unit for biodiversity markets – unlike carbon markets which use tonnes of CO2 as their standard measure. “Biodiversity is not fungible,” the IAPB framework reads. “So projects will be funded based on specific circumstances and outcomes.”

In COP16 host Colombia, for example, local carbon-offset verifier Cercarbono recently approved a methodology to rewards conservation projects that can demonstrate the health of “indicator species” – plants and animals that only thrive in healthy ecosystems.

Fossil fuel transition pledge left out of COP16 draft agreement

Marien from Friends of the Earth argues that a biodiversity offsetting market would be impossible in practice because with carbon “you can still have some kind of measurement”, while with biodiversity “there is none”.

“What we see is that there are so many different projects, so many different measurements. And each organisation, each company which wants to do the offset, they choose their own measurement – cherry-picking of indicators,” Marien told Climate Home News.

Small but growing

The biodiversity market is still relatively small. A report by the Compensate Foundation, a carbon-offsetting non-profit, shows that the eight most developed biodiversity credit schemes covered just 800,000 hectares of land, with only $8 million pledged in May 2023. The market is still “immature” but evolving fast, it added.

At least 11 large project developers are already working with biocredits to help pay to protect species, ecosystems and habitats: Savimbo, CreditNature, ValueNature, Replanet, Terrasos, Ekos, South Pole, Environment Bank, Wilderlands, CarbonZ and Orsa Besparingsskog.

Around 30 governments are also working on their own schemes. Some are focused on delivering net gains – meaning ecosystems must end up in a better state than when they started. The UK’s Biodiversity Net Gain approach and Australia’s Nature Repair Bill fit into this category.

New Zealand has also developed a biodiversity credit system known as Aotearoa, which sells credits to companies through voluntary contributions, certifying them as having a “nature-positive” impact in the local area. The actual conservation work is done by landowners and Indigenous people.

The apparent popularity of biodiversity credits at COP16 suggests the market could grow rapidly, experts said. IIED’s Ducros noted that one reason for the high level of interest is that under the UN nature negotiations, not much public money has yet been pledged from countries to a global biodiversity fund.

The outcomes of COP16 did little to buck this trend, as negotiators were unable to reach an agreement on scaling up biodiversity finance and only around $163 million in fresh contributions were added to a scarce pool in the Global Biodiversity Framework Fund.

Ducros added that voluntary initiatives such as the IAPB are likely to become a reference for additional efforts to ensure quality in the biocredit market.

“There needs to be supporting regulation at the national level as well as the financial architecture, which refers to standards or verification,” the researcher said.

(Reporting by Mariel Lozada; editing by Sebastián Rodríguez, Joe Lo and Megan Rowling)