This article will be updated throughout the day and an edited version will be sent out each evening as a newsletter – you can sign up here.

Text offers two far-apart visions for finance goal

Early on Thursday morning, the COP29 Presidency released a draft document intended to serve as the basis for a deal on a post-2025 goal for climate finance for developing countries.

As expected, the text leaves the most contentious issues undecided including who pays, how much and what the structure of the goal should be.

The text has two main options for how the goal would look: the first reflects developing-country preferences, and the second is what developed countries want to see.

Option one includes an annual goal starting from 2025 and running until 2035, while option two is a goal to be reached by 2035, giving wealthy nations longer to ramp up to meet it.

India, donor countries give up on Just Energy Transition Partnership – German official

Option one says the finance would come from developed to developing countries – although it also accepts developing countries being “invite[d]” to provide finance “voluntarily” as long as this does not count towards the main goal.

Option two refers to the money coming from a “wide range of sources and instruments, including public, private and innovative sources, from bilateral and multilateral channels”.

It states that developed countries should take the lead but also includes “efforts of other countries with the economic capacity to contribute”, as well as accounting for current bilateral and multilateral efforts, and finance mobilised by all other climate finance providers.

Option one says the goal should include finance provided by developed countries’ governments as well as private finance mobililsed by developed countries’ governments. These are the same categories included in the current $100-billion-a-year goal, which this goal will replace.

Coalition against fossil fuel subsidies expands but misses initial targets

But option two includes a much broader array of finance including innovative sources. It does not specify – but these could be measures like taxes on plane tickets or financial transactions. The word “including” leaves this list of sources open-ended and there are fears this could allow developed countries to include money from carbon markets.

While option one would just have a provision and mobilisation goal, option two would have a mobilisation goal led by developed-country governments, as well as a bigger, broader investment goal.

While all governments agree that only developing countries should be eligible to receive the finance, the extent to which the world’s poorest countries (LDCs) and small island developing states (SIDS) should be prioritised is still not agreed.

LDCs and SIDS want an annual minimum of $220bn and $39bn respectively. But in the text this has been left in square brackets, meaning it is not agreed. Alternative options are phrasing stressing the particular vulnerability of LDCs and SIDs and text that does not mention country groups but instead call for “equitable resource distribution”.

Experts react to “good, bad and ugly”

Joe Thwaites, a climate finance expert at the Natural Resources Defense Council said ”the text caricatures developed and developing country positions on what the main goal should be. The Presidency needs to propose an option 3 that bridges the two.”

Harjeet Singh, a campaigner from the Fossil Fuel Non Proliferation Treaty Initiative, said it included options that were good, bad and “some downright ugly”. He expressed concern that there are no sub-goals for cutting emissions, adapting to climate change and for the loss and damage caused by climate change.

Laurie van der Burg, Oil Change International’s global public finance manager, pointed to language that promotes scaling up climate finance from new sources and instruments including “high-integrity voluntary carbon markets”.

“Labelling carbon credits as climate finance – which they are unreservedly not – should be axed from the text or risk creating a dangerous escape route for polluters,” she said.

She also warned that, unlike previous drafts, this draft text does not have an option ruling out counting investments in fossil fuel infrastructure as part of climate finance. “This is fundamentally incompatible with the goals of the Paris Agreement,” Van der Burg noted.

The COP29 presidency said in a statement to media that it did not think presenting a wide range of numbers for the financial goal would have been useful in this version of the draft.

“The next iteration – to be released tonight – will be shorter and will contain numbers based on our view of possible landing zones for consensus,” it added.

Young people and children at a COP29 event calling for the inclusion of youth in national climate plans on November 21, 2024 in Baku, Azerbaijan. (Photo: UN Climate Change – Kamran Guliyev)

Countries lament “unworkable” texts as COP29 enters “endgame”

The Azeri presidency noted in its press statement on Thursday as the plenary – called a “Qurultay” according to local tradition – got underway that COP29 is “now in the endgame”, adding “we believe that a breakthrough in Baku is in sight”.

It said the package of draft texts released this morning – including on issues from cutting emissions to adaptation and gender – had finance at the centre and contained options “to address the key concerns of all groups”.

“Everyone must engage with the texts and with each other so that they are ready to make the ambitious choices we all need,” the presidency added. Updated draft versions are expected on Thursday night.

Speaking at the plenary, Wopke Hoekstra, the EU’s commissioner for climate action, urged the COP29 presidency to “step up the leadership” after expressing disappointment with a package of texts that he called “unworkable”.

As climate-vulnerable countries, we know what kind of finance we need

On the new climate finance goal (NCQG), Hoekstra said “we are very far away” from what’s needed for an agreement. He reiterated the EU’s conviction that “everyone who can should contribute” funding towards the goal, alongside developed countries – which experts interpret as a way to include China and wealthy Gulf states as donors.

Hoekstra added that public finance should go primarily to address adaptation efforts and to the most vulnerable nations.

Echoing the EU’s position on contributors, John Podesta, the US special advisor on climate change, said that making sure “all capable” countries pitch in towards the target is “an essential element of the package”.

Divisions visible in the finance draft text also surfaced at today’s plenary. Uganda, speaking on behalf of the G77 and China group representing most developing countries, said they were disappointed that developed countries had still not put a figure for the finance goal on the table.

“We have been very, very clear that we should not leave Baku without a number,” Uganda’s lead negotiator Adonia Ayebare emphasised. On Wednesday, he and Bolivia’s chief negotiator referred to a rumoured $200bn amount for international public finance as a “joke”.

He lamented that the text still includes a focus on private investment flows from North to South, while the G77 group believes the NCQG “is not an investment goal”. He also reiterated that the goal is the “sole obligation” of developed countries.

Speaking on behalf of the African group, Kenya’s climate change envoy, Ali Mohamed, echoed the concerns over an “unacceptable” focus on investment flows and the absence of numbers in the text. He added that “clarity and firm commitment” was needed from developed countries on how they would fulfill their climate finance obligations.

Samoa, speaking on behalf of small island developing states (SIDS), also lamented the missing finance amount which the delegate described as “a critical element of the puzzle”.

“The time for political games is over,” he added, calling for the inclusion of minimum allocations earmarked for SIDS and least developed countries.

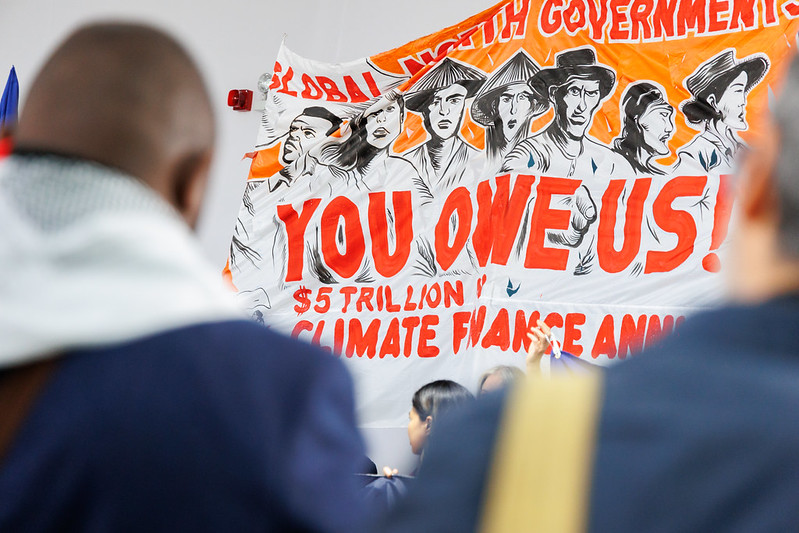

Demonstrators at the COP29 cenue demand climate finance in the “trillions” in Baku, Azerbaijan. (Photo: UNFCCC)

Emissions-cutting texts criticised for “big step back”

Among the texts out Thursday morning, the COP presidency unveiled new drafts on how to cut carbon emissions, which signal a choice on where under the talks countries will address mitigation – including last year’s UAE Global Stocktake decisions on energy transition. This has yet to be decided until now, with less than two days until COP29 officially ends.

The other strand for discussing emissions cuts, the non-binding Mitigation Work Programme, was significantly weakened in a text that shrank from ten to three pages. The presidency removed all mentions of the transition away from fossil fuels, the tripling of renewables and mandates for the next round of NDC climate plans due next year.

Instead, these mandates were kept alive under a different section of the talks: the Global Stocktake, which was last year’s main outcome in Dubai. This text still features options mentioning the fossil fuel transition. It also includes an option for “no text” at all.

In Thursday’s plenary, countries expressed strong concerns on the weakening of the mitigation work programme, which in previous versions circulated unofficially mentioned last year’s historic agreement to “transition away from fossil fuels”.

The United States’ John Podesta said he was deeply concerned over a “glaring imbalance” in the text and the “unacceptable treatment” of mitigation, adding that nothing carries forward the outcome of COP28 when countries agreed to “transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems” for the first time.

Ed Miliband, the UK minister for energy security and net zero, said that the text “doesn’t yet meet the moment”. Speaking about provisions on emission-cutting, he added that, in a world facing increasing disasters, “standing still is a retreat”.

Speaking on behalf of the “Umbrella Group” of developed countries, Australia’s climate minister Chris Bowen said that mentions of the energy transition are “hidden, pared back and minimal” in the current texts on mitigation.

Bowen criticised this as a “big step back in this current moment of crisis” in his statement to the plenary. Germany’s climate envoy Jennifer Morgan expressed similar disappointment, adding there is “no progress, no signals” for the new upcoming round of NDCs due in 2025.

“This cannot be our response to the suffering of millions of people around the world. We must do better,” she added.

Samoa, speaking on behalf of small island states – which are highly exposed to rising seas – said there is “still some way to go” before reaching a balanced package of decisions at COP29, voicing concerns over a lack of ambition on mitigation.

Samoa’s minister added that the COP29 outcome needs to “protect the space for deep emission reductions” and not “undermine” the progress achieved at COP28 in Dubai last year when countries agreed to “transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems” for the first time.

Mexico commits to net zero by 2050

Oil-producer Mexico announced a commitment to net-zero emissions by 2050 at a press conference in Baku on Thursday morning – though details remain sparse. It was the last G20 nation not to have set a net-zero commitment.

Jose Luis Samaniego, the Mexican environment ministry’s climate lead, told journalists that the new Mexican government was “running the numbers and having the necessary conversations to engage in a robust trajectory to net zero by 2050 that we will include in our long-term planning”.

“We don’t think this will be easy but we have never had a stronger political mandate to do so,” he added.

In the photos taken on October 28, 2021, it shows a solar energy park in Jalisco, Mexico. (CGGT/Ulan/Pool / Latin America News Agency via Reuters Connect)

David Waskow, head of global climate policy at the World Resources Institute think-tank, said: “Mexico’s new commitment to reach net-zero by 2050 is a critical step to accelerate its climate efforts and attract investments for a low-carbon economy.”

Samaniego also said Mexico would submit an updated new national climate plan (NDC) next year and increase its ambition with a clearer and more credible emissions-reduction target for 2035, which could potentially include specific carbon budgets per sector.

It plans to ramp up renewables and invest in energy efficiency, as well as cleaning up damage to nature like rivers, among other measures, he added.

Mexico, North America’s fastest growing economy, has ramped up power generation from oil and gas for the past three years, in part driven by a drop in hydroelectricity generation due to drought.

Jorge Villareal, director of Mexican think-tank Iniciativa Climática de México, told Climate Home he “celebrates” the announcement and said it was “without a doubt an ambitious one”. Villareal added the next critical step will be to develop a clear roadmap to achieve the target.